Opioid Utilization and Perception of Pain Control in Hospitalized Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study of 11 Sites in 8 Countries

BACKGROUND: Hospitalized patients are frequently treated with opioids for pain control, and receipt of opioids at hospital discharge may increase the risk of future chronic opioid use.

OBJECTIVE: To compare inpatient analgesic prescribing patterns and patients’ perception of pain control in the United States and non-US hospitals. DESIGN: Cross-sectional observational study.

SETTING: Four hospitals in the US and seven in seven other countries.

PARTICIPANTS: Medical inpatients reporting pain.

MEASUREMENTS: Opioid analgesics dispensed during the first 24-36 hours of hospitalization and at discharge; assessments and beliefs about pain.

RESULTS: We acquired completed surveys for 981 patients, 503 of 719 patients in the US and 478 of 590 patients in other countries. After adjusting for confounding factors, we found that more US patients were given opioids during their hospitalization compared with patients in other countries, regardless of whether they did or did not report taking opioids prior to admission (92% vs 70% and 71% vs 41%, respectively; P < .05), and similar trends were seen for opioids prescribed at discharge. Patient satisfaction, beliefs, and expectations about pain control differed between patients in the US and other sites.

LIMITATIONS: Limited number of sites and patients/country.

CONCLUSIONS: In the hospitals we sampled, our data suggest that physicians in the US may prescribe opioids more frequently during patients’ hospitalizations and at discharge than their colleagues in other countries, and patients have different beliefs and expectations about pain control. Efforts to curb the opioid epidemic likely need to include addressing inpatient analgesic prescribing practices and patients’ expectations regarding pain control.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

RESULTS

We approached 1,309 eligible patients, of which 981 provided informed consent, for a response rate of 75%; 503 from the US and 478 patients from other countries (Figure). In unadjusted analyses, we found no significant differences between US and non-US patients in age (mean age 51, SD 15 vs 59, SD 19; P = .30), race, ethnicity, or Charlson comorbidity index scores (median 2, IQR 1-3 vs 3, IQR 1-4; P = .45). US patients had shorter lengths of stay (median 3 days, IQR 2-4 vs 6 days, IQR 3-11; P = .04), a more frequent history of illicit drug use (33% vs 6%; P = .003), a higher frequency of psychiatric illness (27% vs 8%; P < .0001), and more were receiving opioid analgesics prior to admission (38% vs 17%; P = .007) than those hospitalized in other countries (Table 1, Appendix 1). The primary admitting diagnoses for all patients in the study are listed in Appendix 2. Opioid prescribing practices across the individual sites are shown in Appendix 3.

Patients Taking Opioids Prior to Admission

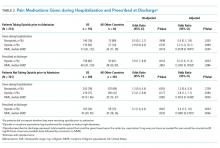

After adjusting for relevant covariates, we found that more patients in the US were given opioids during their hospitalization and in higher doses than patients from other countries and more were prescribed opioids at discharge. Fewer patients in the US were dispensed nonopioid analgesics during their hospitalization than patients from other countries, but this difference was not significant (Table 2). Appendix 4 shows the types of nonopioid pain medications prescribed in the US and other countries.

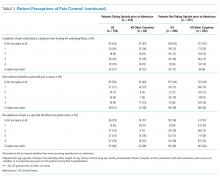

After adjustment for relevant covariates, US patients reported greater pain severity at the time they completed their pain surveys. We found no significant difference in satisfaction with pain control between patients from the US and other countries in the models, regardless of whether we included average pain score or opioid receipt during hospitalization in the model (Table 3).

In unadjusted analyses, compared with patients hospitalized in other countries, more patients in the US stated that they would like a stronger dose of analgesic if they were still in pain, though the difference was nonsignificant, and US patients were more likely to agree with the statement that people become addicted to pain medication easily and less likely to agree with the statement that it is easier to endure pain than deal with the side effects of pain medications (Table 3).

Patients Not Taking Opioids Prior to Admission

After adjusting for relevant covariates, we found no significant difference in the proportion of US patients provided with nonopioid pain medications during their hospitalization compared with patients in other countries, but a greater percentage of US patients were given opioids during their hospitalization and at discharge and in higher doses (Table 2).

After adjusting for relevant covariates, US patients reported greater pain severity at the time they completed their pain surveys and greater pain severity in the 24-36 hours prior to completing the survey than patients from other countries, but we found no difference in patient satisfaction with pain control (Table 3). After we included the average pain score and whether or not opioids were given to the patient during their hospitalization in this model, patients in the US were more likely to report a higher level of satisfaction with pain control than patients in all other countries (P = .001).

In unadjusted analyses, compared with patients hospitalized in other countries, those in the US were less likely to agree with the statement that good patients avoid talking about pain (Table 3).