Improving the Transition of Intravenous to Enteral Antibiotics in Pediatric Patients with Pneumonia or Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

BACKGROUND: Despite national recommendations for early transition to enteral antimicrobials, practice variability has existed at our hospital.

OBJECTIVE: The aim of this study was to increase the proportion of enterally administered antibiotic doses for Pediatric Hospital Medicine patients aged >60 days admitted for uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia or skin and soft tissue infections from 44% to 75% in eight months.

METHODS: This quality improvement study was conducted at a large, urban, academic children’s hospital. The study population included Hospital Medicine patients aged >60 days with diagnoses of pneumonia or skin and soft tissue infections. Interventions included education on intravenous and enteral antibiotic charge differentials, documentation of transition plan, structured discussions of transition criteria, and real-time identification of failures with feedback. Our process measure was the total number of enteral antibiotic doses divided by all antibiotic doses in patients receiving enteral medications on the same day. An annotated statistical process control chart tracked the impact of interventions on the administration route of antibiotic doses over time. Additional outcome measures included antimicrobial costs per patient encounter using average wholesale prices and length of stay.

RESULTS: The percentage of enterally administered antibiotic doses increased from 44% to 80% within eight months. Antimicrobial costs per patient encounter and the associated standard deviation of costs for our target diagnoses decreased by 70% and 84%, respectively. Average length of stay did not change.

CONCLUSIONS: Standardized communication about criteria for transition from intravenous to enteral antibiotics can lead to earlier transitions for patients with pneumonia or skin and soft tissue infections, subsequently reducing costs and prescribing variability.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

To identify the target patient population, we investigated IV antimicrobials frequently used in HM patients. Ampicillin and clindamycin are commonly used IV antibiotics, most frequently corresponding with the diagnoses of CAP and SSTI, respectively, accounting for half of all antibiotic use on the HM service. Amoxicillin, the enteral equivalent of ampicillin, can achieve sufficient concentrations to attain the pharmacodynamic target at infection sites, and clindamycin has high bioavailability, making them ideal options for early transition. Our institution’s robust antimicrobial stewardship program has published local guidelines on using amoxicillin as the enteral antibiotic of choice for uncomplicated CAP, but it does not provide guidance on the timing of transition for either CAP or SSTI; the clinical team makes this decision.

HM attendings were surveyed to determine the criteria used to transition from IV to enteral antibiotics for patients with CAP or SSTI. The survey illustrated practice variability with providers using differing clinical criteria to signal the timing of transition. Additionally, only 49% of respondents (n = 37) rated themselves as “very comfortable” with residents making autonomous decisions to transition to enteral antibiotics. We chose to use the administration of other enteral medications, instead of discharge readiness, as an objective indicator of a patient’s readiness to transition to enteral antibiotics, given the low-risk patient population and the ability of the enteral antibiotics commonly used for CAP and SSTI to achieve pharmacodynamic targets.

The study population included patients aged >60 days admitted to HM with CAP or SSTI treated with any antibiotic. We excluded patients with potential complications or significant progression of their disease process, including patients with parapneumonic effusions or chest tubes, patients who underwent bronchoscopy, and patients with osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, or preseptal or orbital cellulitis. Past medical history and clinical status on admission were not used to exclude patients.

Interventions

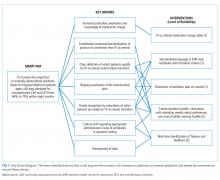

Our multidisciplinary team, formed in January 2017, included HM attendings, HM fellows, pediatric residents, a critical care attending, a pharmacy resident, and an antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist. Under the guidance of QI coaches, the residents on the HM QI team developed and tested all interventions on their team and then determined which interventions would spread to the other four teams. The nursing director of our primary HM unit disseminated project updates to bedside nurses. A simplified failure mode and effects analysis identified areas for improvement and potential interventions. Interventions focused on the following key drivers (Figure 1): increased prescriber awareness of medication charge, standardization of conversion from IV to enteral antibiotics, clear definition of the patients ready for transition, ongoing evaluation of the antimicrobial plan, timely recognition by prescribers of patients ready for transition, culture shift regarding the appropriate administration route in the inpatient setting, and transparency of data. The team implemented sequential Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles13 to test the interventions.

Charge Table

To improve knowledge about the increased charge for commonly used IV medications compared with enteral formulations, a table comparing relative charges was shared during monthly resident morning conferences and at an HM faculty meeting. The table included charge comparisons between ampicillin and amoxicillin and IV and enteral clindamycin.