Adverse Events Experienced by Patients Hospitalized without Definite Medical Acuity: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Physicians often consider various nonmedical factors in hospital admission decision-making and may admit socially tenuous patients despite low-acuity medical needs. Evidence showing whether these patients are subject to the same risks of hospitalization as those considered definitely medically appropriate is limited. Our study sought to inform this risk/benefit discussion by quantifying the number of adverse events (AEs) experienced by both patient populations by using the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Global Trigger Tool methodology. We found no difference in the percentage of admissions with AEs between the two groups (27.3% vs 29.3%; risk ratio 0.93, 95% CI 0.65-1.34, P = .70) nor in AEs per 1,000-patient days (76.8 vs 70.4; incidence rate ratio = 1.09, 95% CI 0.77-1.55, P = .61). Thus, the number of AEs experienced during hospitalization does not appear to be related to the appropriateness of admission based on the level of medical acuity.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Admissions without definite medical acuity were longer than those with definite medical acuity (6.6 vs 6.0 days, P = .038), but there was no difference in emergency department readmissions within 48 hours or hospital readmissions within 30 days (Table 1).

Adverse Events

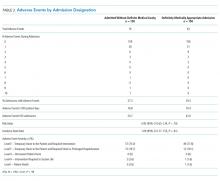

We identified 76 AEs in 41 admissions without definite medical acuity (range 0-10 AEs per admission) and 63 AEs in 44 definitely medically appropriate admissions (range 0-4 AEs per admission). The percentage of admissions with AE (27.3% vs 29.3%; RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.65-1.34, P = .70) and the rate of AE/1,000 patient-days (76.8 vs 70.4; IRR 1.09, 95% CI 0.77-1.55, P = .61) did not show statistically significant differences. The distribution of AE severity was similar between the two groups (Table 2). Most identified AEs caused temporary harm to the patient and were rated at severity levels E or F. Severe AEs, including at least one level I (patient death), occurred in both groups. The complete listing of positive triggers leading to adverse event identification by group and severity is available in Appendix Table 3.

DISCUSSION

By using a robust, standardized method, we found that patients admitted without definite medical acuity experienced the same number of inpatient AEs as patients admitted for definitely medically appropriate reasons. While the groups were relatively similar overall in terms of demographics and chronic comorbidity, we found evidence of social vulnerability in the group admitted without definite medical acuity in the form of increased rates of homelessness, triage physician concern regarding the lack of outpatient social support, and disposition-related reasons for admission. That both groups suffered harm―including patient death―while admitted to the hospital is striking, in particular for those patients who were admitted because of the lack of suitable outpatient options.

The potential limitations to the generalizability of this work include the single-site, safety-net setting and the use of individual physician determination of admission appropriateness. The proportion of admissions without definite medical acuity reported here is similar to that reported by previously published admission decision-making studies,2,3 and the rate of AEs observed is similar to rates measured in other studies using the trigger tool methodology.5,13 These similarities suggest some commonality across settings. Our study treats triage physician assessment as the marker of difference in defining the two groups and is an inherently subjective assessment that is reflective of real-world, holistic decision-making. Notably, the triage physician assessment was corroborated by corresponding differences in the ESI score, an acute triage assessment completed by a clinician outside of our team.

This study adds foundational knowledge to the risk/benefit discussion surrounding the decision to admit. Physician admission decisions are likely influenced by concern for the safety of vulnerable patients. Our results suggest that considering the risk of hospitalization itself in this decision-making remains important.