Resuming Anticoagulation following Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding among Patients with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation—A Microsimulation Analysis

BACKGROUND: Among patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) who have sustained an upper gastrointestinal bleed (UGIB), the benefits and harms of oral anticoagulation change over time. Early resumption of anticoagulation increases recurrent bleeding, while delayed resumption exposes patients to a higher risk of ischemic stroke. We therefore set out to estimate the expected benefit of resuming anticoagulation as a function of time after UGIB among patients with NVAF.

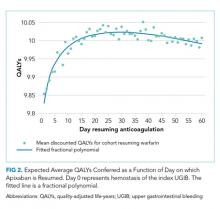

METHODS: We created a decision-analytic model estimating discounted quality-adjusted life-years when patients with NVAF resume anticoagulation on each day following UGIB. We simulated from a health system perspective over a lifelong time horizon.

RESULTS: Peak utility for warfarin was achieved by resumption 41 days after hemostasis from the index UGIB. Resumption between days 32 and 51 produced greater than 99.9% of the peak utility. Peak utility for apixaban was achieved by resumption 32 days after the index UGIB. Resumption between days 21 and 47 produced greater than 99.9% of the peak utility. Of input parameters, results were most sensitive to underlying stroke risk. Specifically, across the range of CHA2DS2-Vasc scores, the optimal day of resumption varied by around 11 days for patients resuming warfarin and by around 15 days for patients resuming apixaban. Results were less sensitive to underlying risk of rebleeding.

CONCLUSIONS: For patients with NVAF following UGIB, warfarin is optimally restarted approximately six weeks following hemostasis, and apixaban is optimally restarted approximately one month following hemostasis. Modest changes to this timing based on probability of thromboembolic stroke are reasonable.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

DISCUSSION

Anticoagulation is frequently prescribed for patients with NVAF, and hemorrhagic complications are common. Although anticoagulants are withheld following hemorrhages, scant evidence to inform the optimal timing of reinitiation is available. In this microsimulation analysis, we found that the optimal time to reinitiate anticoagulation following UGIB is around 41 days for warfarin and around 32 days for apixaban. We have further demonstrated that the optimal timing of reinitiation can vary by nearly two weeks, depending on a patient’s underlying risk of stroke, and that early reinitiation is more sensitive to rebleeding risk than late reinitiation.

Prior work has shown that early reinitiation of anticoagulation leads to higher rates of recurrent hemorrhage while failure to reinitiate anticoagulation is associated with higher rates of stroke and mortality.1-4,36 Our results add to the literature in a number of important ways. First, our model not only confirms that anticoagulation should be restarted but also suggests when this action should be taken. The competing risks of bleeding and stroke have left clinicians with little guidance; we have quantified the clinical reasoning required for the decision to resume anticoagulation. Second, by including the disutility of hospitalization and long-term disability, our model more accurately represents the complex tradeoffs between recurrent hemorrhage and (potentially disabling) stroke than would a comparison of event rates. Third, our model is conditional upon patient risk factors, allowing clinicians to personalize the timing of anticoagulation resumption. Theory would suggest that patients at higher risk of ischemic stroke benefit from earlier resumption of anticoagulation, while patients at higher risk of hemorrhage benefit from delayed reinitiation. We have quantified the extent to which patient-specific risks should change timing. Fourth, we offer a means of improving expected health outcomes that requires little more than appropriate scheduling. Current practice regarding resuming anticoagulation is widely variable. Many patients never resume warfarin, and those that do resume do so after highly varied periods of time.1-5,36 We offer a means of standardizing clinical practice and improving expected patient outcomes.

Interestingly, patient-specific risk of rebleeding had little effect on our primary outcome for warfarin, and a greater effect in our simulation of apixaban. It would seem that rebleeding risk, which decreases roughly exponentially, is sufficiently low by the time period at which warfarin should be resumed that patient-specific hemorrhage risk factors have little impact. Meanwhile, at the shorter post-event intervals at which apixaban can be resumed, both stroke risk and patient-specific bleeding risk are worthy considerations.

Our model is subject to several important limitations. First, our predictions of the optimal day as a function of risk scores can only be as well-calibrated as the input scoring systems. It is intuitive that patients with higher risk of rebleeding benefit from delayed reinitiation, while patients with higher risk of thromboembolic stroke benefit from earlier reinitiation. Still, clinicians seeking to operationalize competing risks through these two scores—or, indeed, any score—should be mindful of their limited calibration and shared variance. In other words, while the optimal day of reinitiation is likely in the range we have predicted and varies to the degree demonstrated here, the optimal day we have predicted for each score is likely overly precise. However, while better-calibrated prediction models would improve the accuracy of our model, we believe ours to be the best estimate of timing given available data and this approach to be the most appropriate way to personalize anticoagulation resumption.

Our simulation of apixaban carries an additional source of potential miscalibration. In the clinical trials that led to their approval, apixaban and other direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) were compared with warfarin over longer periods of time than the acute period simulated in this work. Over a short period of time, patients treated with more rapidly therapeutic medications (in this case, apixaban) would receive more days of effective therapy compared with a slower-onset medication, such as warfarin. Therefore, the relative risks experienced by patients are likely different over the time period we have simulated compared with those measured over longer periods of time (as in phase 3 clinical trials). Our results for apixaban should be viewed as more limited than our estimates for warfarin. More broadly, simulation analyses are intended to predict overall outcomes that are difficult to measure. While other frameworks to assess model credibility exist, the fact remains that no extant datasets can directly validate our predictions.37

Our findings are limited to patients with NVAF. Anticoagulants are prescribed for a variety of indications with widely varied underlying risks and benefits. Models constructed for these conditions would likely produce different timing for resumption of anticoagulation. Unfortunately, large scale cohort studies to inform such models are lacking. Similarly, we simulated UGIB, and our results should not be generalized to populations with other types of bleeding (eg, intracranial hemorrhage). Again, cohort studies of other types of bleeding would be necessary to understand the risks of anticoagulation over time in such populations.

Higher-quality data regarding risk of rebleeding over time would improve our estimates. Our literature search identified only one systematic review that could be used to estimate the risk of recurrent UGIB over time. These data are not adequate to interrogate other forms this survival curve could take, such as Gompertz or Weibull distributions. Recurrence risk almost certainly declines over time, but how quickly it declines carries additional uncertainty.

Despite these limitations, we believe our results to be the best estimates to date of the optimal time of anticoagulation reinitiation following UGIB. Our findings could help inform clinical practice guidelines and reduce variation in care where current practice guidelines are largely silent. Given the potential ease of implementing scheduling changes, our results represent an opportunity to improve patient outcomes with little resource investment.

In conclusion, after UGIB associated with anticoagulation, our model suggests that warfarin is optimally restarted approximately six weeks following hemostasis and that apixaban is optimally restarted approximately one month following hemostasis. Modest changes to this timing based on probability of thromboembolic stroke are reasonable.