Internal Medicine Residents’ Exposure to and Confidence in Managing Hospital Acute Clinical Events

BACKGROUND: Internal Medicine (IM) residency graduates should be able to manage hospital emergencies, but the rare and critical nature of such events poses an educational challenge. IM residents’ exposure to inpatient acute clinical events is currently unknown.

OBJECTIVE: We developed an instrument to assess IM residents’ exposure to and confidence in managing hospital acute clinical events.

METHODS: We administered a survey to all IM residents at our institution assessing their exposure to and confidence in managing 50 inpatient acute clinical events. Exposures assessed included mannequin-based simulation or management of hospital-based events as a part of a team or independently in a leadership role. Confidence was rated on a five-point scale and dichotomized to “confident” versus “not confident.” Results were analyzed by multivariable logistic regression to assess the relationship between exposure and confidence accounting for year in training.

RESULTS: A total of 140 of 170 IM residents (82%) responded. Postgraduate year 1 (PGY-1) residents had managed 31.3% of acute events independently vs 71.7% of events for PGY-3/4 residents (P < .0001). In multivariable analysis, residents’ confidence increased with level of training (PGY-1 residents were confident to manage 24.9% of events vs 72.5% of events for PGY-3/4 residents, P < .0001) and level of exposure, independent of training year (P = .001). Events with the lowest levels of exposure and confidence for graduating residents were identified.

CONCLUSIONS: IM residents’ confidence in managing inpatient acute events correlated with level of training and clinical exposure. We identified events with low levels of resident exposure and confidence that can serve as targets for future curriculum development.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

We also examined residents’ self-reported confidence for each PGY class in aggregate and for each clinical acute scenario. Confidence was investigated in a dichotomized manner with a “definitely can” rating indicating “Confident” and with “probably can,” “neutral,” “probably cannot,” or “definitely cannot” ratings indicating “Not Confident” to manage the condition independently. Dichotomization thus allowed us to set a high bar for confidence, reflecting the self-perceived ability of the residents to manage the conditions as future independent physicians.

We used logistic regression models with the generalized estimating equations (GEE) approach to take into account the repeated measures of 50 clinical acute clinical events assessed for each resident. We compared the distribution of self-reported exposure and confidence among different PGY classes and examined the relationship between confidence and self-reported exposure stratified by level of training. We also assessed the independent effect of exposure on confidence controlling for level of training in a multivariable logistic regression model.

RESULTS

A total of 140 of 170 IM residents completed the survey (82% overall response rate: 72% of all PGY-1 residents, 86% of PGY-2 residents, and 89% of PGY-3/4 residents). In total, 41 PGY-1 residents (29% of respondents), 50 PGY-2 residents (36%), and 49 PGY-3 or PGY-4 residents (35%) participated. The majority of residents were in the Categorical IM training track (106 residents, 76% of respondents), whereas the remainder of respondents were in various subspecialty training tracks within our IM residency program, including Primary Care (14 residents, 10%), and four-year tracks, including Global Health (six residents, 4%), and Medicine-Pediatrics (14 residents, 10%).

Assessment of Exposure

Residents reported increasingly independent exposures as they progressed through residency training. PGY-1 residents on average had never seen 16.3% of the 50 acute events, whereas PGY-3/4 residents had never seen only 4.0% of the events (P < .0001). PGY-1 residents had managed 31.3% of events independently (or both independently and in simulation) as opposed to 71.7% of events for PGY-3/4 residents (P < .0001). Simulation alone accounted for a substantial proportion of exposures (16.4%) for PGY-1 residents, but this was significantly lower for PGY-2 or PGY-3/4 residents (P < .0001), who reported a greater percentage of exposures in nonsimulation clinical scenarios either independently or as a part of an inpatient team. There were no outlier residents who reported lower exposure compared with their PGY peers.

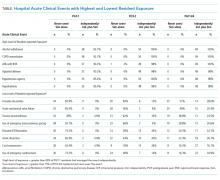

There was a wide spectrum of resident-reported exposures when individual acute events were examined (Table, full data in Supplementary Appendix Table 1). Events with the highest levels of exposure, which >85% of PGY-1 residents had managed independently, included alcohol withdrawal, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation, rapid atrial fibrillation, agitated delirium, hypertensive urgency, and hyperkalemia. Events with the lowest levels of exposure, which at least 15% of graduating residents had never encountered in the hospital, included the following eight of 50 events (16%): torsades de pointes (51% of PGY-3/4 residents), acute mechanical valve failure (49%), tension pneumothorax (38.8%), use of emergency transcutaneous pacing (38.8%), elevated intracranial pressure (ICP)/herniation (24.5%), aortic dissection (22.4%), cord compression (16.3%), and use of emergency cardioversion (16.3%). Several PGY-3/4 residents had managed several of these events only in mannequin simulations, including torsades de pointes (41%), transcutaneous pacing (33%), and tension pneumothorax (24%).