Increasing Mobility via In-hospital Ambulation Protocol Delivered by Mobility Technicians: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial

BACKGROUND: Ambulating medical inpatients may improve outcomes, but this practice is often overlooked by nurses who have competing clinical duties.

OBJECTIVE: This study aimed to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of dedicated mobility technician-assisted ambulation in older inpatients.

DESIGN: This study was a single-blind randomized controlled trial.

SETTING: Patients aged ≥60 years and admitted as medical inpatients to a tertiary care center were recruited.

INTERVENTION: Patients were randomized into two groups to participate in the ambulation protocol administered by a dedicated mobility technician. Usual care patients were not seen by the mobility technician but were not otherwise restricted in their opportunity to ambulate.

MEASUREMENTS: Primary outcomes were length of stay and discharge disposition. Secondary outcomes included change in mobility measured by six-clicks score, daily steps measured by Fitbit, and 30-day readmission.

RESULTS: Control (n = 52) and intervention (n = 50) groups were not significantly different at baseline. Of patients randomized to the intervention group, 74% participated at least once. Although the intervention did not affect the primary outcomes, the intervention group took nearly 50% more steps than the control group (P = .04). In the per protocol analysis, the six-clicks score significantly increased (P = .04). Patients achieving ≥400 steps were more likely to go home (71% vs 46%, P = .01).

CONCLUSIONS: Attempted ambulation three times daily overseen by a dedicated mobility technician was feasible and increased the number of steps taken. A threshold of 400 steps was predictive of home discharge. Further studies are needed to establish the appropriate step goal and the effect of assisted ambulation on hospital outcomes.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics were summarized as means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables and as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. The t-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test was applied to compare continuous characteristics between the intervention and control groups. Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was applied to compare categorical characteristics. Given its skewed distribution, the length of stay was log-transformed and compared between the two groups using Student’s t-test. Chi-squared test was used to compare categorical outcomes. The analysis of final six-clicks scores was adjusted for baseline scores, and the least-square estimates are provided. A linear mixed effects model was used to compare the number of daily steps taken because each participant had multiple steps measured. Results were adjusted for prehospital activity. In addition to comparing the total steps taken by each group, we determined the proportion of patients who exceeded a particular threshold by taking the average number of steps per day for all subjects and relating it to home discharge using the Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curve. An optimal cut-off was determined to maximize the Youden index. We also compared the proportion of patients who exceeded 900 steps because this value was previously reported as an important threshold.32 All analyses were conducted using intention-to-treat principles. We also conducted a per-protocol analysis in which we limited the intervention group to those who received at least one assisted ambulation session. A dose-response analysis was also performed, in which patients were categorized as not receiving the therapy, receiving sessions on one or two days, or receiving them on more than two days.

All analyses were conducted using R-studio (Boston, MA). Statistical significance was defined as a P-value < .05. Given that this is a pilot study, the results were not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Characteristics of patients in the intervention and control groups are shown in Table 1. The patients were mostly white and female, with an average age in the mid-70s (range 61-98). All measures evaluated were not significantly different between the intervention and control groups. However, more patients in the intervention group had a prehospital activity level classified as independent.

Table 2 demonstrates the feasibility of the intervention. Of patients randomized to the intervention group, 74% were ambulated at least once. Once enrolled, the patients successfully participated in assisted ambulation for about two-thirds of their hospital stay. However, the intervention was delivered for only one-third of the total length of stay because most patients were not enrolled on admission. On average, the mobility technicians made 11 attempts to ambulate each patient and 56% of these attempts were successful. The proportion of unsuccessful attempts did not change over the course of the study. The reasons for unsuccessful attempts included patient refusal (n = 102) or unavailability (n = 68), mobility technicians running out of time (n = 2), and other (n = 12).

Initially, the mobility technicians were not available on weekends. In addition, they were often reassigned to other duties by their nurse managers, who were dealing with staffing shortages. As the study progressed, we were able to secure the mobility technicians to work seven days per week and to convince the nurse managers that their role should be protected. Consequently, the median number [IQR] of successful attempts increased from 1.5 [0, 2] in the first two months to 3 [0, 5] in the next three months and finally to 5 [1.5, 13] in the final months (P < .002). The median visit duration was 10 minutes, with an interquartile range of 6-15 minutes.

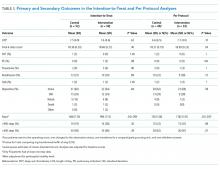

In the intention-to-treat analysis, patients in the intervention group took close to 50% more steps than did the control patients. After adjustment for prehospital activity level, the difference was not statistically significant. The intervention also did not significantly affect the length of stay or discharge disposition (Table 3). In the per protocol analysis, the difference in the step count was significant, even after adjustment. The six-clicks score also significantly increased.

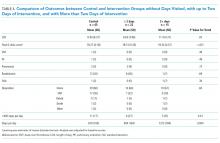

To assess for dose response, we compared outcomes among patients who received no intervention, those who received two or fewer days of intervention, and those who received more than two days of intervention (Table 4). The length of stay was significantly longer in patients with more than two days of intervention, likely reflecting greater opportunities for exposure to the intervention. The longer intervention time significantly increased the six-clicks score.

We examined the relationship between steps achieved and discharge disposition. Patients who achieved at least 900 steps more often went home than those who did not (79% vs. 56%, P < .05). The ROC for the model of discharge disposition using steps taken as the only predictor had an area under the curve of 0.67, with optimal discrimination at 411 steps. At a threshold of 400 steps, the model had a sensitivity of 75.9% and a specificity of 51.4%. Patients achieving 400 steps were more likely to go home than those who did not achieve that goal (71% vs. 46%, P =.01). More patients in the intervention group achieved the 900 step goal (28% vs. 19%, P = .30) and the 400 step goal (66% vs. 58%, P = .39), but neither association reached statistical significance.