Barriers to Early Hospital Discharge: A Cross-Sectional Study at Five Academic Hospitals

BACKGROUND: Understanding the issues delaying hospital discharges may inform efforts to improve hospital throughput.

OBJECTIVE: This study was conducted to identify and determine the frequency of barriers contributing to delays in placing discharge orders. DESIGN: This was a prospective, cross-sectional study. Physicians were surveyed at approximately 8:00 AM, 12:00 PM, and 3:00 PM and were asked to identify patients that were “definite” or “possible” discharges and to describe the specific barriers to writing discharge orders.

SETTING: This study was conducted at five hospitals in the United States. PARTICIPANTS: The study participants were attending and housestaff physicians on general medicine services.

PRIMARY OUTCOMES AND MEASURES: Specific barriers to writing discharge orders were the primary outcomes; the secondary outcomes included discharge order time for high versus low team census, teaching versus nonteaching services, and rounding style. RESULTS: Among 1,584 patient evaluations, the most common delays for patients identified as “definite” discharges (n = 949) were related to caring for other patients on the team or waiting to staff patients with attendings. The most common barriers for patients identified as “possible” discharges (n = 1,237) were awaiting patient improvement and for ancillary services to complete care. Discharge orders were written a median of 43-58 minutes earlier for patients on teams with a smaller versus larger census, on nonteaching versus teaching services, and when rounding on patients likely to be discharged first (all P < .003).

CONCLUSIONS: Discharge orders for patients ready for discharge are most commonly delayed because physicians are caring for other patients. Discharges of patients awaiting care completion are most commonly delayed because of imbalances between availability and demand for ancillary services. Team census, rounding style, and teaching teams affect discharge times.

Sample Size

We stopped collecting data after obtaining a convenience sample of 5% of total discharges at each study site or on the study end date, which was May 31, 2016, whichever came first.

Data Analysis

Data were collected and managed using a secure, web-based application electronic data capture tool (REDCap), hosted at Denver Health. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture, Nashville, Tennessee) is designed to support data collection for research studies.27 Data were then analyzed using SAS Enterprise Guide 5.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). All data entered into REDCap were reviewed by the principal investigator to ensure that data were not missing, and when there were missing data, a query was sent to verify if the data were retrievable. If retrievable, then the data would be entered. The volume of missing data that remained is described in our results.

Continuous variables were described using means and standard deviations (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) based on tests of normality. Differences in the time that the discharge orders were placed in the electronic medical record according to morning patient census, teaching versus nonteaching service, and rounding style were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Linear regression was used to evaluate the effect of patient census on discharge order time. P < .05 was considered as significant.

RESULTS

We conducted 1,584 patient evaluations through surveys of 254 physicians over 156 days. Given surveys coincided with the existing work we had full participation (ie, 100% participation) and no dropout during the study days. Median (IQR) survey time points were 8:30

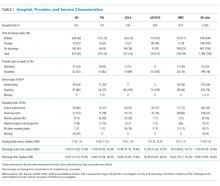

The characteristics of the five hospitals participating in the study, the patients’ final discharge status, the types of physicians surveyed, the services on which they were working, the rounding styles employed, and the median starting daily census are summarized in Table 1. The majority of the physicians surveyed were housestaff working on teaching services, and only a small minority structured rounds such that patients ready for discharge were seen first.

Over the course of the three surveys, 949 patients were identified as being definite discharges at any time point, and the large majority of these (863, 91%) were discharged on the day of the survey. The median (IQR) time that the discharge orders were written was 11:50

During the initial morning survey, 314 patients were identified as being definite discharges for that day (representing approximately 6% of the total number of patients being cared for, or 33% of the patients identified as definite discharges throughout the day). Of these, the physicians thought that 44 (<1% of the total number of patients being cared for on the services) could have been discharged on the previous day. The most frequent reasons cited for why these patients were not discharged on the previous day were “Patient did not want to leave” (n = 15, 34%), “Too late in the day” (n = 10, 23%), and “No ride” (n = 9, 20%). The remaining 10 patients (23%) had a variety of reasons related to system or social issues (ie, shelter not available, miscommunication).

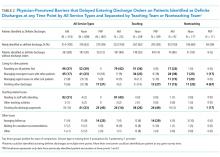

At the morning time point, the most common barriers to discharge identified were that the physicians had not finished rounding on their team of patients and that the housestaff needed to staff their patients with their attending. At noon, caring for other patients and tending to the discharge processes were most commonly cited, and in the afternoon, the most common barriers were that the physicians were in the process of completing the discharge paperwork for those patients or were discharging other patients (Table 2). When comparing barriers on teaching to nonteaching teams, a higher proportion of teaching teams were still rounding on all patients and were working on discharge paperwork at the second survey. Barriers cited by sites were similar; however, the frequency at which the barriers were mentioned varied (data not shown).

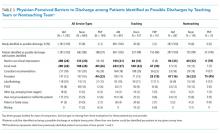

The physicians identified 1,237 patients at any time point as being possible discharges during the day of the survey and these had a mean (±SD) of 1.3 (±0.5) barriers cited for why these patients were possible rather than definite discharges. The most common were that clinical improvement was needed, one or more pending issues related to their care needed to be resolved, and/or awaiting pending test results. The need to see clinical improvement generally decreased throughout the day as did the need to staff patients with an attending physician, but barriers related to consultant recommendations or completing procedures increased (Table 3). Of the 1,237 patients ever identified as possible discharges, 594 (48%) became a definite discharge by the third call and 444 (36%) became a no discharge as their final status. As with definite discharges, barriers cited by sites were similar; however, the frequency at which the barriers were mentioned varied.

Among the 949 and 1,237 patients who were ever identified as definite or possible discharges, respectively, at any time point during the study day, 28 (3%) and 444 (36%), respectively, had their discharge status changed to no discharge, most commonly because their clinical condition either worsened or expected improvements did not occur or that barriers pertaining to social work, physical therapy, or occupational therapy were not resolved.

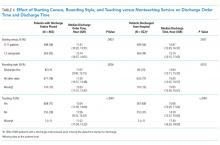

The median time that the discharge orders were entered into the electronic medical record was 43 minutes earlier if patients were on teams with a lower versus a higher starting census (P = .0003), 48 minutes earlier if they were seen by physicians whose rounding style was to see patients first who potentially could be discharged (P = .0026), and 58 minutes earlier if they were on nonteaching versus teaching services (P < .0001; Table 4). For every one-person increase in census, the discharge order time increased by 6 minutes (β = 5.6, SE = 1.6, P = .0003).