The Basement Flight

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Her white blood cell count was 11.9 x 10 9 /L (67% neutrophils, 24.2% lymphocytes, 6% monocytes, and 2% eosinophils), hemoglobin 11.2 g/dL, and platelet count 278,000/mm 3 . Her complete metabolic panel was normal. The C-reactive protein (CRP) was 24 mg/L (normal range, < 4.9) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 103 mm/hour (normal range, 0-32). A venous blood gas (VBG) showed a pH of 7.42 and pCO2 39. An EKG demonstrated sinus tachycardia.

The combination of the patient’s tachypnea, hypoxemia, respiratory distress, and obesity is striking. Her lack of adventitious lung sounds is surprising given her CT findings, but the sensitivity of chest auscultation may be limited in obese patients. Her laboratory findings help narrow the diagnostic frame: she has mild anemia and leukocytosis along with significant inflammation. The normal CO2 concentration on VBG is concerning given the degree of her tachypnea and reflects significant alveolar hypoventilation.

This marked inflammation with diffuse lung findings again raises the possibility of an inflammatory or, less likely, infectious disorder. Sjogren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and juvenile dermatomyositis can present in young women with interstitial lung disease. She does have exposure to pets and hypersensitivity pneumonitis can worsen rapidly with continued exposure. Another possibility is that she has an underlying immunodeficiency such as common variable immunodeficiency, although a history of recurrent infections such as pneumonia, bacteremia, or sinusitis is lacking.

An echocardiogram should be performed. In addition, laboratory evaluation for the aforementioned autoimmune causes of interstitial lung disease, immunoglobulin levels, pulmonary function testing (if available as an inpatient), and potentially a bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), and biopsy should be pursued. The BAL and biopsy would be helpful in evaluating for infection and interstitial lung disease in an expeditious manner.

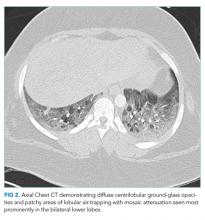

A chest CT without contrast was done and compared to the scan from two months prior. New diffuse, ill-defined centrilobular ground-glass opacities were evident throughout the lung fields; dilation of the main pulmonary artery was unchanged, and previously seen ground-glass opacities had resolved. There were patchy areas of air-trapping and mosaic attenuation in the lower lobes (Figure 2).

Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated a right ventricular systolic pressure of 58 mm Hg with flattened intraventricular septum during systole. Left and right ventricular systolic function were normal. The left ventricular diastolic function was normal. Pulmonary function testing demonstrated a FEV1/FVC ratio of 100 (112% predicted), FVC 1.07 L (35 % predicted) and FEV1 1.07 L (39% predicted), and total lung capacity was 2.7L (56% predicted) (Figure 3). Single-breath carbon monoxide uptake in the lung was not interpretable based on 2017 European Respiratory Society (ERS)/American Thoracic Society (ATS) technical standards.

This information is helpful in classifying whether this patient’s primary condition is cardiac or pulmonary in nature. Her normal left ventricular systolic and diastolic function make a cardiac etiology for her pulmonary hypertension less likely. Further, the combination of pulmonary hypertension, a restrictive pattern on pulmonary function testing, and findings consistent with interstitial lung disease on cross-sectional imaging all suggest a primary pulmonary etiology rather than a cardiac, infectious, or thromboembolic condition. While chronic thromboembolic hypertension can result in nonspecific mosaic attenuation, it typically would not cause centrilobular ground-glass opacities nor restrictive lung disease. Thus, it seems most likely that this patient has a progressive pulmonary process resulting in hypoxia, pulmonary hypertension, centrilobular opacities, and lower-lobe mosaic attenuation. Considerations for this process can be broadly categorized as one of the childhood interstitial lung disease (chILD). While this differential diagnosis is broad, strong consideration should be given to hypersensitivity pneumonitis, chronic aspiration, sarcoidosis, and Sjogren’s syndrome. An intriguing possibility is that the patient’s “response to azithromycin” two months prior was due to the avoidance of an inhaled antigen while she was in the hospital; a detailed environmental history should be explored. The normal polysomnography after tonsilloadenoidectomy makes it unlikely that OSA is a major contributor to her current presentation. However, since the surgery was seven years ago, and her BMI is presently 58 kg/m2 she remains at risk for OSA and obesity-hypoventilation syndrome. Polysomnography should be done after her acute symptoms improve.

She was started on 5 mm Hg of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) at night after a sleep study on room air demonstrated severe OSA with a respiratory disturbance index of 13 events per hour. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), anti-Jo-1 antibody, anti-RNP antibody, anti-Smith antibody, anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibody were negative as was the histoplasmin antibody. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level was normal. Mycoplasma IgM and IgG were negative. IgE was 529 kU/L (normal range, <114).

This evaluation reduces the likelihood the patient has Sjogren’s syndrome, SLE, dermatomyositis, or ANCA-associated pulmonary disease. While many patients with dermatomyositis may have negative serologic evaluations, other findings usually present such as rash and myositis are lacking. The negative ANCA evaluation makes granulomatosis with polyangiitis and microscopic polyangiitis very unlikely given the high sensitivity of the ANCA assay for these conditions. ANCA assays are less sensitive for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), but the lack of eosinophilia significantly decreases the likelihood of EGPA. ACE levels have relatively poor operating characteristics in the evaluation of sarcoidosis; however, sarcoidosis seems unlikely in this case, especially as patients with sarcoidosis tend to have low or normal IgE levels. Patients with asthma can have elevated IgE levels. However, very elevated IgE levels are more common in other conditions, including allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) and the Hyper-IgE syndrome. The latter manifests with recurrent infections and eczema, and is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. However, both the Hyper-IgE syndrome and ABPA have much higher IgE levels than seen in this case. Allergen-specific IgE testing (including for antibodies to Aspergillus) should be sent. It seems that an interstitial lung disease is present; the waxing and waning pattern and clinical presentation, along with the lack of other systemic findings, make hypersensitivity pneumonitis most likely.

The family lived in an apartment building. Her symptoms started when the family’s neighbor recently moved his outdoor pigeon coop into his basement. The patient often smelled the pigeons and noted feathers coming through the holes in the wall.

One of the key diagnostic features of hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) is the history of exposure to a potential offending antigen—in this case likely bird feathers—along with worsening upon reexposure to that antigen. HP is primarily a clinical diagnosis, and testing for serum precipitants has limited value, given the high false negative rate and the frequent lack of clinical symptoms accompanying positive testing. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid may reveal lymphocytosis and reduced CD4:CD8 ratio. Crackles are commonly heard on examination, but in this case were likely not auscultated due to her obese habitus. The most important treatment is withdrawal of the offending antigen. Limited data suggest that corticosteroid therapy may be helpful in certain HP cases, including subacute, chronic and severe cases as well as patients with hypoxemia, significant imaging findings, and those with significant abnormalities on pulmonary function testing (PFT).

A hypersensitivity pneumonitis precipitins panel was sent with positive antibodies to M. faeni, T. Vulgaris, A. Fumigatus 1 and 6, A. Flavus, and pigeon serum. Her symptoms gradually improved within five days of oral prednisone (60 mg). She was discharged home without dyspnea and normal oxygen saturation while breathing ambient air. A repeat echocardiogram after nighttime CPAP for 1 week demonstrated a right ventricular systolic pressure of 17 mm Hg consistent with improved pulmonary hypertension.