Less Lumens-Less Risk: A Pilot Intervention to Increase the Use of Single-Lumen Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters

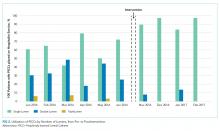

To reduce risk of complications, existing guidelines recommend use of peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) with the minimal number of lumens. This recommendation, however, is difficult to implement in practice. We conducted a pilot study to increase the use of single-lumen PICCs in hospitalized patients. The intervention included (1) education for physicians, pharmacists, and nurses; (2) changes to the electronic PICC order-set that set single lumen PICCs as default; and (3) criteria defining when use of multilumen PICCs is appropriate. The intervention was supported by real-time monitoring and feedback. Among 226 consecutive PICCs, 64.7% of preintervention devices were single lumen versus 93.6% postintervention (P < .001). The proportion of PICCs with an inappropriate number of lumens decreased from 25.6% preintervention to 2.2% postintervention (P < .001). No cases suggesting inadequate venous access or orders for the placement of a second PICC were observed. Implementing a single-lumen PICC default and providing education and indications for multilumen devices improved PICC appropriateness.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

DISCUSSION

In this single center, pre–post quasi-experimental study, a multimodal intervention based on the MAGIC criteria significantly reduced the use of multilumen PICCs. Additionally, a trend toward reductions in complications, including CLABSI and catheter occlusion, was also observed. Notably, these changes in ordering practices did not lead to requests for additional devices or replacement with a multilumen PICC when a single-lumen device was inserted. Collectively, our findings suggest that the use of single-lumen devices in a large direct care service can be feasibly and safely increased through this approach. Larger scale studies that implement MAGIC to inform placement of multilumen PICCs and reduce PICC-related complications now appear necessary.

The presence of a PICC, even for short periods, significantly increases the risk of CLABSI and is one of the strongest predictors of venous thrombosis risk in the hospital setting.19,24,25 Although some factors that lead to this increased risk are patient-related and not modifiable (eg, malignancy or intensive care unit status), increased risk linked to the gauge of PICCs and the number of PICC lumens can be modified by improving device selection.9,18,26 Deliberate use of PICCs with the least numbers of clinically necessary lumens decreases risk of CLABSI, venous thrombosis and overall cost.17,19,26 Additionally, greater rates of occlusion with each additional PICC lumen may result in the interruption of intravenous therapy, the administration of costly medications (eg, tissue plasminogen activator) to salvage the PICC, and premature removal of devices should the occlusion prove irreversible.8

We observed a trend toward decreased PICC complications following implementation of our criteria, especially for the outcomes of CLABSI and catheter occlusion. Given the pilot nature of this study, we were underpowered to detect a statistically significant change in PICC adverse events. However, we did observe a statistically significant increase in the rate of single-lumen PICC use following our intervention. Notably, this increase occurred in the setting of high rates of single-lumen PICC use at baseline (64%). Therefore, an important takeaway from our findings is that room for improving PICC appropriateness exists even among high performers. This finding In turn, high baseline use of single-lumen PICCs may also explain why a robust reduction in PICC complications was not observed in our study, given that other studies showing reduction in the rates of complications began with considerably low rates of single-lumen device use.19 Outcomes may improve, however, if we expand and sustain these changes or expand to larger settings. For example, (based on assumptions from a previously published simulation study and our average hospital medicine daily census of 98 patients) the increased use of single-over multilumen PICCs is expected to decrease CLABSI events and venous thrombosis episodes by 2.4-fold in our hospital medicine service with an associated cost savings of $74,300 each year.17 Additionally, we would also expect the increase in the proportion of single-lumen PICCs to reduce rates of catheter occlusion. This reduction, in turn, would lessen interruptions in intravenous therapy, the need for medications to treat occlusion, and the need for device replacement all leading to reduced costs.27 Overall, then, our intervention (informed by appropriateness criteria) provides substantial benefits to hospital savings and patient safety.

After our intervention, 98% of all PICCs placed were found to comply with appropriate criteria for multilumen PICC use. We unexpectedly found that the most important factor driving our findings was not oversight or order modification by the pharmacy team or VAST nurses, but rather better decisions made by physicians at the outset. Specifically, we did not find a single instance wherein the original PICC order was changed to a device with a different number of lumens after review from the VAST team. We attribute this finding to receptiveness of physicians to change ordering practices following education and the redesign of the default EMR PICC order, both of which provided a scientific rationale for multilumen PICC use. Clarifying the risk and criteria of the use of multilumen devices along with providing an EMR ordering process that supports best practice helped hospitalists “do the right thing”. Additionally, setting single-lumen devices as the preselected EMR order and requiring text-based justification for placement of a multilumen PICC helped provide a nudge to physicians, much as it has done with antibiotic choices.28

Our study has limitations. First, we were only able to identify complications that were captured by our EMR. Given that over 70% of the patients in our study were discharged with a PICC in place, we do not know whether complications may have developed outside the hospital. Second, our intervention was resource intensive and required partnership with pharmacy, VAST, and hospitalists. Thus, the generalizability of our intervention to other institutions without similar support is unclear. Third, despite an increase in the use of single-lumen PICCs and a decrease in multilumen devices, we did not observe a significant reduction in all types of complications. While our high rate of single-lumen PICC use may account for these findings, larger scale studies are needed to better study the impact of MAGIC and appropriateness criteria on PICC complications. Finally, given our approach, we cannot identify the most effective modality within our bundled intervention. Stepped wedge or single-component studies are needed to further address this question.

In conclusion, we piloted a multimodal intervention to promote the use of single-lumen PICCs while lowering the use of multilumen devices. By using MAGIC to create appropriate indications, the use of multilumen PICCs declined and complications trended downwards. Larger, multicenter studies to validate our findings and examine the sustainability of this intervention would be welcomed.