A Dark Horse Diagnosis

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient’s case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similar to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is

unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

He had presented to the emergency department five days earlier with fever, flank pain, nausea, vomiting, and weakness. At that time, he had a temperature of 38.2°C, but vital signs otherwise had been normal. Laboratory studies had revealed WBC count 14.0 × 103/μL, hemoglobin 13.7 g/dL, platelet count 175 × 103/μL, sodium 129 mmol/L, chloride 97 mmol/dL, bicarbonate 23 mmol/L, creatinine 1.1 mg/dL, and total bilirubin 1.6 mg/dL. Urinalysis had been negative. He had received one liter of intravenous normal saline and ketorolac for pain and had been discharged with the diagnosis of a viral illness.

A picture of a progressive, subacute illness with multisystem involvement appears to be emerging, and there are several abnormalities consistent with infection, including fever, leukocytosis with bandemia, thrombocytopenia, renal dysfunction, and elevated bilirubin. His borderline hypotension may be due to uninterrupted use of his antihypertensive medication in the setting of poor oral intake or may indicate incipient sepsis. Focal sacral tenderness raises the possibility of vertebral osteomyelitis or epidural abscess, either from a contiguous focus of infection from the surrounding structures, or as a site of seeding from bacteremia. His prior confusion episodes might have been secondary to a systemic process; however, CNS imaging should be done, given the history of confusion and recent fall. Further diagnostic studies are warranted, including: blood cultures; peripheral blood smear; imaging of the spine, chest, abdomen, and pelvis; electrocardiogram; and possibly echocardiogram. Although noninfectious etiologies should not be discounted, the constellation of findings is more compatible with infection.

Two sets of blood cultures and a viral respiratory swab were obtained. Computed tomography (CT) of the head without contrast was negative for acute bleeding or other intracranial pathology. Lumbosacral radiography revealed degenerative changes with intact alignment of the sacrum. The patient was admitted with plans to pursue lumbar puncture if altered mental status recurred. The viral swab was negative. Within 24 hours, one set of blood cultures (both bottles) grew lactose-negative, oxidase-negative, gram-negative rods.

Gram-negative rods (GNRs) rarely are contaminants in blood cultures and should be considered significant until proven otherwise. Prompt empiric therapy and investigation to identify the primary source of bacteremia must be initiated. Although the most common GNRs isolated from blood cultures are enteric coliform organisms such as E. coli, Klebsiella, and Enterobacter, these typically are lactose-positive. Additional possibilities should be considered, including Salmonella species or other organisms comprising the “HACEK” group. This latter group is commonly associated with endocarditis, but the majority are oxidase-positive and have more fastidious growth requirements. Although there are other gram-negative organisms to consider, they have other distinguishing characteristics that have not been indicated in the microbiology results. Broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy is appropriate while awaiting the final identification of the GNR. A thorough search for a primary source and secondary sites of hematogenous seeding should be conducted. His only localizing symptom was tenderness over the sacrum, and this should be further assessed by sensitive imaging such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The identity of the GNR would guide further diagnostic evaluation. For example, a respiratory organism such as Haemophilus influenzae would prompt a CT scan of the chest. Isolation of an enteric or a coliform GNR such as E. coli would prompt abdominal and pelvic imaging to assess for occult abscess. An “HACEK” group organism would prompt echocardiography to evaluate for endocarditis.

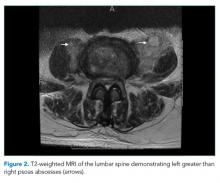

He was started on piperacillin–tazobactam. GNR bacteremia without a clear source prompted a CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with and without contrast. The images were unremarkable, with the exception of a signal abnormality in the left psoas muscle concerning for abscess (Figure 1). MRI of the same region revealed L2-4 osteomyelitis and discitis with bilateral psoas abscesses but without epidural abscess (Figure 2).