Smoking Cessation after Hospital Discharge: Factors Associated with Abstinence

Hospitalization offers tobacco smokers an opportunity to quit smoking, but factors associated with abstinence from tobacco after hospital discharge are poorly understood. We analyzed data from a multisite, randomized controlled trial testing a smoking cessation intervention for 1,357 hospitalized cigarette smokers who planned to quit. Using multiple logistic regression, we assessed factors identifiable in the hospital that were independently associated with biochemically confirmed tobacco abstinence 6 months after discharge. Biochemically confirmed abstinence at 6 months (n = 218, 16%) was associated with a smoking-related primary discharge diagnosis (Adjusted Odds Ratio[AOR] = 1.98, 95% CI: 1.41–2.77), greater confidence in the ability to quit smoking (AOR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.07–1.60), and stronger intention to quit (plan to quit after discharge vs. try to quit; AOR=1.68, 95% CI: 1.19-2.38). In conclusion, smokers hospitalized with a tobacco-related illness and those with greater confidence and intention to quit after discharge are more likely to sustain abstinence in the long term. Hospital clinicians’ efforts to promote smoking cessation should target smokers’ confidence and motivation to quit.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Analysis

Bivariate associations of baseline predictor variables and biochemically confirmed abstinence were examined using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables. Using multiple logistic regression analyses, we identified variables that were independently associated with confirmed abstinence. The final models included all factors that were associated with cessation in the bivariate analysis (P < .10), factors associated with abstinence in the literature regardless of statistical significance (gender, AUDIT-C score),4 study site, and study condition. A two-sided p value of <.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the 1,357 smokers enrolled in the trial are reported in Table 1. One-third of participants had a smoking-related discharge diagnosis. The median self-reported confidence in quitting was three on a five-point scale, and nearly half of the participants reported planning to stay abstinent after discharge. At six-month follow-up, 75% of participants completed the assessment, and seven-day tobacco abstinence was reported by 389 participants (29%) and biochemically confirmed in 218 participants (16%).

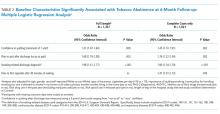

Results of the multiple logistic regression analysis predicting biochemically confirmed abstinence at six months are presented in Table 2. Factors independently associated with confirmed abstinence were a smoking-related primary discharge diagnosis (AOR = 1.98, 95% CI: 1.41-2.77), greater confidence in the ability to quit smoking (AOR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.07-1.60), and stronger intention to quit (plan to stay abstinent after discharge vs. try to stay abstinent; AOR = 1.68, 95% CI: 1.19-2.38). Similar variables emerged as independent predictors of abstinence when the analysis was limited to complete cases, with an exception that one additional predictor, time to first cigarette after 30 minutes of waking, had statistical significance at the 0.05 level (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

We examined the associations between factors that were identifiable in the hospital and postdischarge tobacco abstinence among a general sample of hospitalized patients enrolled in a smoking cessation trial. The odds of biochemically confirmed abstinence at six months were higher among participants who reported higher levels of confidence in quitting smoking, those reporting having a definite plan to quit (vs. try to) after discharge, and those with a smoking-related primary discharge diagnosis.

Our findings are largely consistent with the prior literature on this topic, which has demonstrated that increased confidence in quitting, having a plan to quit smoking, and the presence of a smoking-related disease are associated with quit success at follow-up among hospital patients as well as in the general adult population.3-7 Our finding that nicotine dependence predicted quit success in the complete case analysis, but not when imputing smoking status, aligns with prior studies of hospitalized smokers, which have shown an inconclusive relationship between nicotine dependence and quit success.6,8 Despite a clear relationship of dependence to quit success among adult smokers, evidence in the hospital literature has been inconsistent. This inconsistency is likely due to the differing interventions across studies (eg, counseling vs. pharmacotherapy), the differing outcome variables (eg, self-report vs. biochemically verified), as well as the different patient populations selected to participate.

Unfortunately, smoking cessation is infrequently addressed in routine health care settings,15,16 highlighting a gap in care. For example, one survey study16 found that while many health care professionals report asking about smoking status and advising smokers to quit, fewer clinicians assess smokers’ interest or intention to stop smoking, assist with cessation, or arrange follow-up. Our results indicate that assessing an inpatient smoker’s intentions, motivation, and confidence for cessation and attempting to improve low levels of these factors could enhance cessation success. Because motivation is a malleable construct, repeated assessment by hospital clinicians of a patient’s motivation and confidence to quit is needed.

Our results also confirm that inpatient efforts to improve smoking cessation postdischarge should target smokers’ resolve to quit and confidence in the ability to succeed. Motivational interventions and cognitive-behavioral therapy are effective strategies that can resolve ambivalence and increase confidence to quit and should be components of brief interventions delivered in inpatient settings.17,18 Although individuals with a smoking-related illness may already possess some resolve to quit based on their illness, they may be candidates for interventions focused primarily on developing self-efficacy. Indeed, supporting self-efficacy is a major goal of effective bedside counseling and can be bolstered via problem-solving, motivational techniques, and education about pharmacotherapy during a tobacco-specific consult such as the one that these participants experienced. Armed with these resources, smokers with and without a smoking-related disease may be more likely to execute a plan to quit after discharge.

A study limitation is that our results can be generalized only to hospital inpatients who were willing to try to quit smoking after discharge, because the parent trial excluded smokers with lower levels of motivation. Similarly, these results may not be generalizable to obstetric or psychiatric inpatients, who were excluded from this trial.

In conclusion, our results underscore the importance of assessing motivation and self-efficacy in hospitalized smokers and targeting these factors in intervention efforts. Although future research should aim to identify better methods to alter these factors, in the short run, hospital clinicians could target these factors when discussing tobacco use with inpatient smokers.