Mental Health Conditions and Unplanned Hospital Readmissions in Children

OBJECTIVE: Mental health conditions (MHCs) are prevalent among hospitalized children and could influence the success of hospital discharge. We assessed the relationship between MHCs and 30-day readmissions.

METHODS: This retrospective, cross-sectional study of the 2013 Nationwide Readmissions Database included 512,997 hospitalizations of patients ages 3 to 21 years for the 10 medical and 10 procedure conditions with the highest number of 30-day readmissions. MHCs were identified by using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision-Clinical Modification codes. We derived logistic regression models to measure the associations between MHC and 30-day, all-cause, unplanned readmissions, adjusting for demographic, clinical, and hospital characteristics.

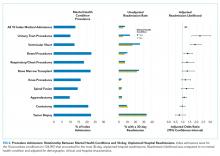

RESULTS: An MHC was present in 17.5% of medical and 13.1% of procedure index hospitalizations. Readmission rates were 17.0% and 6.2% for medical and procedure hospitalizations, respectively. In the multivariable analysis, compared with hospitalizations with no MHC, hospitalizations with MHCs had higher odds of readmission for medical admissions (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.23; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.19-1.26] and procedure admissions (AOR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.15-1.33). Three types of MHCs were associated with higher odds of readmission for both medical and procedure hospitalizations: depression (medical AOR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.49-1.66; procedure AOR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.17-1.65), substance abuse (medical AOR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.18-1.30; procedure AOR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.11-1.43), and multiple MHCs (medical AOR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.37-1.50; procedure AOR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.11-1.44).

CONCLUSIONS: MHCs are associated with a higher likelihood of hospital readmission in children admitted for medical conditions and procedures. Understanding the influence of MHCs on readmissions could guide strategic planning to reduce unplanned readmissions for children with cooccurring physical and mental health conditions.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Index Procedure Admissions, Mental Health Conditions, and Hospital Readmission

Index Procedure Admissions Combined

Specific Index Procedure Admissions

For specific index procedure admissions, the rate of 30-day hospital readmission ranged from 2.2% for knee procedures to 33.6% for tumor biopsy. For 3 (ie, urinary tract, ventricular shunt, and bowel procedures) of the 10 specific index procedure hospitalizations, having an MHC was associated with higher adjusted odds of 30-day readmission (AOR range, 1.38-2.27; Figure 2).

In total, adjusting for sociodemographic, clinical, and hospital characteristics, MHCs were associated with an additional 2501 medical readmissions and 217 procedure readmissions beyond what would have been expected if MHCs were not associated with readmissions.

DISCUSSION

MHCs are common among pediatric hospitalizations with the highest volume of readmissions; MHCs were present in approximately 1 in 5 medical and 1 in 7 procedure index hospitalizations. Across medical and procedure admissions, the adjusted likelihood of unplanned, all-cause 30-day readmission was 25% higher for children with versus without an MHC. The readmission likelihood varied by the type of medical or procedure admission and by the type of MHC. MHCs had the strongest associations with readmissions following hospitalization for diabetes and urinary tract procedures. The MHC categories associated with the highest readmission likelihood were depression, substance abuse, and multiple MHCs.

The current study complements existing literature by helping establish MHCs as a prevalent and important risk factor for hospital readmission in children. Estimates of the prevalence of MHCs in hospitalized children are between 10% and 25%,10,11,32 and prevalence has increased by as much as 160% over the last 10 years.29 Prior investigations have found that children with an MHC tend to stay longer in the hospital compared with children with no MHC.32 Results from the present study suggest that children with MHCs also experience more inpatient days because of rehospitalizations. Subsequent investigations should strive to understand the mechanisms in the hospital, community, and family environment that are responsible for the increased inpatient utilization in children with MHCs. Understanding how the receipt of mental health services before, during, and after hospitalization influences readmissions could help identify opportunities for practice improvement. Families report the need for better coordination of their child’s medical and mental health care,33 and opportunities exist to improve attendance at mental health visits after acute care encounters.34 Among adults, interventions that address posthospital access to mental healthcare have prevented readmissions.35

Depression was associated with an increased risk of readmission in medical and procedure hospitalizations. As a well-known risk factor for readmission in adult patients,21 depression can adversely affect and exacerbate the physical health recovery of patients experiencing acute and chronic illnesses.14,36,37 Depression is considered a modifiable contributor that, when controlled, may help lower readmission risk. Optimal adherence with behavior and medication treatment for depression is associated with a lower risk of unplanned 30-day readmissions.14-16,19 Emerging evidence demonstrates how multifaceted, psychosocial approaches can improve patients’ adherence with depression treatment plans.38 Increased attention to depression in hospitalized children may uncover new ways to manage symptoms as children transition from hospital to home.

Other MHCs were associated with a different risk of readmission among medical and procedure hospitalizations. For example, ADHD or autism documented during index hospitalization was associated with an increased risk of readmission following procedure hospitalizations and a decreased risk following medical hospitalizations. Perhaps children with ADHD or autism who exhibit hyperactive, impulsive, or repetitive behaviors39,40 are at risk for disrupting their postprocedure wound healing, nutrition recovery, or pain tolerance, which might contribute to increased readmission risk.

MHCs were associated with different readmission risks across specific types of medical or procedure hospitalizations. For example, among medical conditions, the association of readmissions with MHCs was highest for diabetes, which is consistent with prior research.26 Factors that might mediate this relationship include changes in diet and appetite, difficulty with diabetes care plan adherence, and intentional nonadherence as a form of self-harm. Similarly, a higher risk of readmission in chronic medical conditions like asthma, constipation, and sickle cell disease might be mediated by difficulty adhering to medical plans or managing exacerbations at home. In contrast, MHCs had no association with readmission following chemotherapy. In our clinical experience, readmissions following chemotherapy are driven by physiologic problems, such as thrombocytopenia, fever, and/or neutropenia. MHCs might have limited influence over those health issues. For procedure hospitalizations, MHCs had 1 of the strongest associations with ventricular shunt procedures. We hypothesize that MHCs might lead some children to experience general health symptoms that might be associated with shunt malfunction (eg, fatigue, headache, behavior change), which could lead to an increased risk of readmission to evaluate for shunt malfunction. Conversely, we found no relationship between MHCs and readmissions following appendectomy. For appendectomy, MHCs might have limited influence over the development of postsurgical complications (eg, wound infection or ileus). Future research to better elucidate mediators of increased risk of readmission associated with MHCs in certain medical and procedure conditions could help explain these relationships and identify possible future intervention targets to prevent readmissions.

This study has several limitations. The administrative data are not positioned to discover the mechanisms by which MHCs are associated with a higher likelihood of readmission. We used hospital ICD-9-CM codes to identify patients with MHCs. Other methods using more clinically rich data (eg, chart review, prescription medications, etc.) may be preferable to identify patients with MHCs. Although the use of ICD-9-CM codes may have sufficient specificity, some hospitalized children may have an MHC that is not coded. Patients identified by using diagnosis codes could represent patients with a higher severity of illness, patients using medications, or patients whose outpatient records are accessible to make the hospital team aware of the MHC. If documentation of MHCs during hospitalization represents a higher severity of illness, findings may not extrapolate to lower-severity MHCs. As hospitals transition from ICD-9 -CM to ICD-10 coding, and health systems develop more integrated inpatient and outpatient EHRs, diagnostic specificity may improve. We could not analyze the relationships with several potential confounders and explanatory variables that may be related both to the likelihood of having an MHC and the risk of readmission, including medication administration, psychiatric consultation, and parent mental health. Postdischarge health services, including access to a medical home or a usual source of mental healthcare and measures of medication adherence, were not available in the NRD.

Despite these limitations, the current study underscores the importance of MHCs in hospitalized children upon discharge. As subsequent investigations uncover the key drivers explaining the influence of MHCs on hospital readmission risk, hospitals and their local outpatient and community practices may find it useful to consider MHCs when (1) developing contingency plans and establishing follow-up care at discharge,41 (2) exploring opportunities of care integration between mental and physical health care professionals, and (3) devising strategies to reduce hospital readmissions among populations of children.