Teaching Physical Examination to Medical Students on Inpatient Medicine Teams: A Prospective, Mixed-Methods Descriptive Study

Physical examination (PE) is a core clinical competency, and the internal medicine clerkship is a premiere venue for students to develop PE skills. However, clinical rotations often lack opportunities for real-time instruction. We sought to measure the frequency, content, and factors affecting PE instruction during the internal medicine clerkship. We conducted a prospective mixed-methods study at a single academic center. Data were gathered by a student researcher who directly observed inpatient teams over 3 months. We quantified the frequency of PE teaching activities and analyzed daily written observations using qualitative content analysis. PE was most frequently discussed during bedside rounds and least often during workroom rounds. Direct observation of students’ examinations rarely occurred. Multiple factors in the learning environment were posited to affect PE instruction. In brief, we found that residents and attending physicians who are part of internal medicine teaching services do not routinely emphasize PE instruction.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

RESULTS

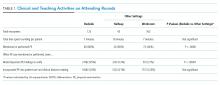

Eighty-one subjects participated in the study: 21 were attending physicians, 12 residents, 21 interns, 11 senior medical students, and 26 junior medical students. We observed 16 distinct inpatient teaching teams and 329 unique patient-related events (discussions and/or patient-clinician encounters), with most events being observed during attending rounds (269/329, or 82%). There were 123 encounters at the bedside, averaging 7 minutes; 43 encounters occurred in the hallway, averaging 8 minutes each; and 163 encounters occurred in a workroom and averaged 7 minutes per patient discussion. We also observed 28 student-patient encounters during pre-round activities and 30 student-patient encounters during new admissions.

Teaching and Direct Observation

During 28 pre-rounding encounters, students usually examined the patient (26 out of 28 instances, 93%) but were observed only 4 times doing so (out of 26 instances, or 15%). During 30 new patient admissions, students examined 27 patients (90%) and had their PE observed 6 times (out of 27 instances, or 22%). There were no significant differences in frequency of these activities (P > .05, chi-squared) between pre-rounds or new admissions.

Observations on Teaching Strategies

In the written observations, we categorized various methods being used to teach PE. Bedside teaching of PE most often involved teachers simply describing or discussing physical findings (42 mentions in observations) or verifying a student’s reported findings (15 mentions). Teachers were also observed to use bedside teaching to contextualize findings (13 mentions), such as relating the quality of bowel sounds to the patient’s constipation or to discuss expected pupillary light reflexes in a neurologically intact patient. Less commonly, attending physicians narrated steps in their PE technique (9 mentions). Students were infrequently encouraged to practice a specific PE skill again (7 mentions) or allowed to re-examine and reconsider their initial interpretations (5 mentions).

DISCUSSION

This observational study of clinical teaching on internal medicine teaching services demonstrates that PE teaching is most likely to occur during bedside rounding. However, even in bedside encounters, most PE instruction is limited to physician team members pointing out significant findings. Although physical findings were mentioned for the majority of patients seen on rounds, attending physicians infrequently verified students’ or residents’ findings, demonstrated technique, or incorporated PE into clinical decision making. We witnessed an alarming dearth of direct observation of students and almost no real-time feedback in performing and teaching PE. Thus, students rarely had opportunities to engage in higher-order learning activities related to PE on the internal medicine rotation.

We posit that the learning environment influenced PE instruction on the internal medicine rotation. To optimize inpatient teaching of PE, attending physicians need to consider the factors we identified in Table 2. Such teaching may be effective with a more limited number of participants and without distraction from technology. Time constraints are one of the major perceived barriers to bedside teaching of PE, and our data support this concern, as teams spent an average of only 7 minutes on each bedside encounter. However, many of the strategies observed to be used in real-time PE instruction, such as validating the learners’ findings or examining patients as a team, naturally fit into clinical routines and generally do not require extra thought or preparation.

One of the key strengths of our study is the use of direct observation of students and their teachers. This study is unique in its exclusive focus on PE and its description of factors affecting PE teaching activities on an internal medicine service. This observational, descriptive study also has obvious limitations. The study was conducted at a single institution during a limited time period. Moreover, the study period June through August, which was chosen based on our observer’s availability, includes the transition to a new academic year (July 1, 2015) when medical students and residents were becoming acclimated to their new roles. Additionally, the data were collected by a single researcher, and observer bias may affect the results of qualitative analysis of journal entries.

In conclusion, this study highlights the infrequency of applied PE skills in the daily clinical and educational workflow of internal medicine teaching teams. These findings may reflect a more widespread problem in clinical education, and replication of our findings at other teaching centers could galvanize faculty development around bedside PE teaching.