A Matter of Urgency: Reducing Clinical Text Message Interruptions During Educational Sessions

BACKGROUND: Text messaging is increasingly replacing paging as a tool to reach physicians on medical wards. However, this phenomenon has resulted in high volumes of nonurgent messages that can disrupt the learning climate.

OBJECTIVE: Our objective was to reduce nonurgent educational interruptions to residents on general internal medicine.

DESIGN, SETTING, PARTICIPANTS: This was a quality improvement project conducted at an academic hospital network. Measurements and interventions took place on 8 general internal medicine inpatient teaching teams.

INTERVENTION: Interventions included (1) refining the clinical communication process in collaboration with nursing leadership; (2) disseminating guidelines with posters at nursing stations; (3) introducing a noninterrupting option for message senders; (4) audit and feedback of messages; (5) adding an alert for message senders advising if a message would interrupt educational sessions; and (6) training and support to nurses and residents.

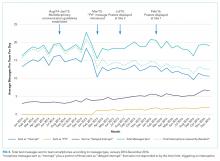

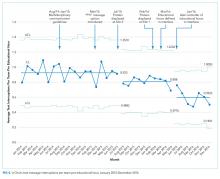

MEASUREMENTS: Interruptions (text messages, phone calls, emails) received by institution-supplied team smartphones were tracked during educational hours using statistical process control charts. A 1-month record of text message content was analyzed for urgency at baseline and following the interventions.

RESULTS: The interruption frequency decreased from a mean of 0.92 (95% CI, 0.88 to 0.97) to 0.59 (95% CI, 0.51 to0.67) messages per team per educational hour from January 2014 to December 2016. The proportion of nonurgent educational interruptions decreased from 223/273 (82%) messages over one month to 123/182 (68%; P < .01).

CONCLUSIONS: Creation of communication guidelines and modification of text message interface with feedback from end-users were associated with a reduction in nonurgent educational interruptions. Continuous audit and feedback may be necessary to minimize nonurgent messages that disrupt educational sessions.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

RESULTS

Incoming phone call logs were available from April 2015 to December 2016, with a mean of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.56 to 0.67) calls per team per educational hour, which did not change over the study period (Supplementary Figure 2). The overall number of calls to team smartphones also did not change during the measurement period. Incoming email data were available from October 2014 to December 2016, with a mean of 0.94 (95% CI, 0.88 to 1.0) emails per team per educational hour, which did not change over the study period (Supplementary Figure 3). Internal medicine service discharges, “Code Blue” announcements, and Critical Care Outreach Team consultations remained stable over the measurement period.

Independent ranking of the combined 4-week samples of educational text interruptions from 2014 and 2016 revealed an initial 3-way agreement on 257/455 (56%) messages (Fleiss Kappa 0.298, fair agreement), which increased to 405/455 (89%) messages after the first joint assessment and reached full consensus after a third joint assessment that included classifying all messages that communicated institution-defined “critical lab” values as “urgent.”

Overall, 71 (16%) messages were classified as “urgent,” 346 (76%) as “nonurgent,” and 38 (8%) as “indeterminate.” After unblinding of the message date and time, 273 text messages were received during the baseline measurement period (November 17 to December 14, 2014) and 182 messages were received during the equivalent time period 2 years later (November 14 to December 11, 2016), consistent with the reduced volume of educational interruptions observed (Figure 4). A total of 426 (94%) messages were sent by nurses, and the remaining ones were sent by pharmacists (n = 20), ward clerks (n = 3), social workers (n = 4), speech language pathologist (n = 1), or device administrator (n = 1).

The proportion of “nonurgent” messages decreased from 223/273 (82%) in 2014 to 123/182 (68%) in 2016 (P ≤ .01). Although the absolute number of urgent messages remained similar (33 in 2014 and 38 in 2016), the proportion of “urgent” messages increased from 12% to 21% of the total messages received (P = .02). Seventeen (6%) messages had indeterminate frequency in 2014 compared to 21 (11.5%) in 2016 (NS).

An audit of consecutive “FYI” messages (November 14-December 11, 2016) revealed an initial agreement in 384/431 (89%), reaching full consensus after repeated joint assessments. A total of 406 (94%) “FYI” messages were appropriately sent, while 10 (2%) represented urgent communications that should have been sent as interruptions. In 15 (4%) cases, the appropriateness of the message was indeterminate.

DISCUSSION

Sequential interventions over a 36-month period were associated with reduced nonurgent text message interruptions during educational hours. A clinical communication process was formally defined to accurately match message urgency with communication modality. A “noninterrupt” option allowed nonurgent text messages to be posted to an electronic message board, rather than causing real-time interruption, thereby reducing the overall volume of interrupting text messages. Modifying the interface to alert potential senders to protected educational hours was associated with reductions in educational interruptions. Through a blinded analysis of the text message content between 2014 and 2016, we determined that nonurgent educational interruptions were significantly reduced, and the number of urgent communications remained constant. Reduced nonurgent interruptions have the potential to improve the learning climate on the medical teaching unit during protected educational hours.