“We’ve Learned It’s a Medical Illness, Not a Moral Choice”: Qualitative Study of the Effects of a Multicomponent Addiction Intervention on Hospital Providers’ Attitudes and Experiences

BACKGROUND: Substance use disorders (SUD) represent a national epidemic with increasing rates of SUD-related hospitalizations. However, most hospitals lack expertise or systems to directly address SUD. Healthcare professionals feel underprepared and commonly hold negative views toward patients with SUD. Little is known about how hospital interventions may affect providers’ attitudes and experiences toward patients with SUD.

OBJECTIVE: To explore interprofessional hospital providers’ perspectives on how integrating SUD treatment and care systems affect providers’ attitudes, beliefs, and experiences.

DESIGN: In-depth semi-structured interviews and focus groups. The study was part of a formative evaluation of the Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT), an interprofessional hospital-based addiction medicine service with rapid-access pathways to post-hospital SUD treatment.

SETTING: Single urban academic hospital in Portland, Oregon.

PARTICIPANTS: Multidisciplinary hospital providers.

MEASUREMENTS: We conducted a thematic analysis using an inductive approach at a semantic level.

RESULTS: Before IMPACT, participants felt that hospitalization did not address addiction, leading to untreated withdrawal, patients leaving against medical advice, chaotic care, and staff “moral distress.” Participants felt that IMPACT “completely reframes” addiction as a treatable chronic disease, improving patient engagement and communication, and humanizing care. Participants valued post-hospital SUD treatment pathways and felt having systems to address SUD reduced burnout and provided relief. Providers noted that IMPACT had limited ability to address poverty or engage highly ambivalent patients.

CONCLUSIONS: Providers’ distress of caring for patients with SUD is not inevitable. Hospital-based SUD interventions can reframe providers’ views of addiction and may have significant implications for clinical care and providers’ well-being.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Substance use disorders (SUD) represent a national epidemic with death rates exceeding those of HIV at its peak.1 Hospitals are increasingly filled with people suffering from medical complications of addiction.2,3 While the US health system spends billions of dollars annually on hospital care for medical problems resulting from SUD,4 most hospitals lack expertise or care systems to directly address SUD or connect people to treatment after discharge. 5,6

Patients with SUD often feel stigmatized in healthcare settings and want providers who understand SUD and how to treat it.7 Providers feel underprepared8 and commonly have negative attitudes toward patients with SUD.9,10 Caring for patients can be a source of resentment, dissatisfaction, and burnout.9 Such negative attitudes can adversely affect patient care. Studies show that patients who perceive discrimination by providers are less likely to complete treatment11 and providers’ negative attitudes may disempower patients.9

Evaluations of hospital interventions for adults with SUD focus primarily on patient-level outcomes of SUD severity,12 healthcare utilization,13 and treatment engagement.14,15 Little is known about how such interventions can affect interprofessional providers’ attitudes and experiences, or how systems-level interventions influence hospital culture.16

We performed a qualitative study of multidisciplinary hospital providers to 1) understand the challenges that hospital providers face in managing care for patients with SUD, and 2) explore how integrating SUD treatment in a hospital setting affects providers’ attitudes, experiences, and perceptions of the care environment. This study was part of a formative evaluation of the Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT). IMPACT includes a hospital-based, interprofessional addiction medicine consultation service and rapid-access pathways to community addiction care after hospitalization.17. IMPACT is an intensive intervention that includes SUD assessments, withdrawal management, medications for addiction (eg, methadone, buprenorphine induction), counseling and behavioral SUD treatment, peer engagement and support, and linkages to community-based addiction care. We described the rationale and design of IMPACT in earlier publications.7,17

METHODS

Setting

We conducted in-person interviews and focus groups (FGs) with interprofessional hospital providers at a single urban academic medical center between February and July 2016, six months after starting IMPACT implementation. Oregon Health and Science University’s (OHSU) institutional review board approved the protocol.

Participants

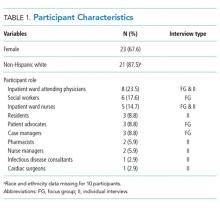

We conducted 12 individual informant interviews (IIs) and 6 (FGs) (each comprising 3-6 participants) with a wide range of providers, including physicians, nurses, social workers, residents, patient advocates, case managers, and pharmacists. In total, 34 providers participated. We used purposive sampling to choose participants with experience both caring for patients with SUD and with exposure to IMPACT. Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Data Collection

We employed 2 different types of interviews. In situations where multiple providers occupied a similar role (eg, social workers), we chose to use a focus group format to elicit a range of perspectives and experiences through participant interaction.18 We conducted individual interviews to gain input from key informants who had unique roles in the program (eg, a cardiac surgeon) and to include providers who would otherwise be unable to participate due to scheduling barriers (eg, residents). We interviewed all participants using a semi-structured interview guide that was developed by an interdisciplinary team, including expert qualitative researchers, IMPACT clinical team members, and other OHSU clinicians (Appendix A). An interviewer who was not a part of the IMPACT clinical team asked all participants about their experience caring for patients with SUD, their experience with IMPACT, and how they might improve care. FGs lasted between 41-57 minutes, and individual key informant interviews lasted between 11-38 minutes. We ended recruitment after reaching theme saturation. Our goal was to achieve saturation across the sample as a whole and not within distinct participant groups. We noted if certain themes were more salient for 1 particular group. We audio-recorded all interviews and FGs. Recordings were transcribed, de-identified, and transferred to ATLAS.ti for data analysis.

Analysis

We conducted a thematic analysis using an inductive approach at the semantic level.19 Using an iterative process, we generated a preliminary coding schema after reviewing an initial selection of transcripts. Coders then independently coded transcripts and met in dyads to both discuss and reconcile codes, and resolve any discrepancies through discussion until reaching a consensus. One coder (DC) coded all transcripts; 3 coders (EP, SPP, MR) divided the transcripts evenly. All authors met periodically to discuss codebook revisions and emergent themes. We identified themes that represented patterns, had meaning to study participants, and captured important findings related to our research questions.19