Relationship between Hospital 30-Day Mortality Rates for Heart Failure and Patterns of Early Inpatient Comfort Care

BACKGROUND: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services rewards hospitals that have low 30-day risk-standardized mortality rates (RSMR) for heart failure (HF).

OBJECTIVE: To describe the use of early comfort care for patients with HF, and whether hospitals that more commonly initiate comfort care have higher 30-day mortality rates.

DESIGN: A retrospective, observational study.

SETTING: Acute care hospitals in the United States.

PATIENTS: A total of 93,920 fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries admitted with HF from January 2008 to December 2014 to 272 hospitals participating in the Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure registry.

EXPOSURE: Early comfort care (defined as comfort care within 48 hours of hospitalization) rate.

MEASUREMENTS: A 30-day RSMR.

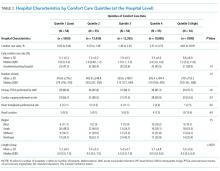

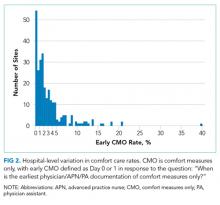

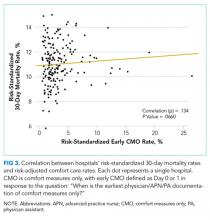

RESULTS: Hospitals’ early comfort care rates were low for patients admitted for HF, with no change over time (2.5% to 2.6%, from 2008 to 2014, P = .56). Rates varied widely (0% to 40%), with 14.3% of hospitals not initiating comfort care for any patients during the first 2 days of hospitalization. Risk-standardized early comfort care rates were not correlated with RSMR (median RSMR = 10.9%, 25th to 75th percentile = 10.1% to 12.0%; Spearman’s rank correlation = 0.13; P = .66).

CONCLUSIONS: Hospital use of early comfort care for HF varies, has not increased over time, and on average, is not correlated with 30-day RSMR. This suggests that current efforts to lower mortality rates have not had unintended consequences for hospitals that institute early comfort care more commonly than their peers.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

DISCUSSION

Among a national sample of US hospitals, we found wide variation in how frequently health care providers deliver comfort care within the first 2 days of admission for HF. A minority of hospitals reported no early comfort care on any patients throughout the 6-year study period, but hospitals in the highest quintile initiated early comfort care rates for at least 1 in 20 HF patients. Hospitals that were more likely to initiate early comfort care had a higher proportion of female and white patients and were less likely to have the capacity to deliver aggressive surgical interventions such as heart transplants. Hospital-level 30-day RSMRs were not correlated with rates of early comfort care.

While the appropriate rate of early comfort care for patients hospitalized with HF is unknown, given that the average hospital RSMR is approximately 12% for fee-for-service Medicare patients hospitalized with HF,12 it is surprising that some hospitals initiated early comfort care on none or very few of their HF patients. It is quite possible that many of these hospitals initiated comfort care for some of their patients after 48 hours of hospitalization. We were unable to estimate the average period of time patients received comfort care prior to dying, the degree to which this varies across hospitals or why it might vary, and whether the length of time between comfort care initiation and death is related to satisfaction with end-of-life care. Future research on these topics would help inform providers seeking to deliver better end-of-life care. In this study, we also were unable to estimate how often early comfort care was not initiated because patients had a good prognosis. However, prior studies have suggested low rates of comfort care or hospice referral even among patients at very high estimated mortality risk.4 It is also possible that providers and families had concerns about the ability to accurately prognosticate, although several models have been shown to perform acceptably for patients hospitalized with HF.13

We found that comfort care rates did not increase over time, even though use of hospice care doubled among Medicare beneficiaries between 2000 and 2012. By way of context, cancer—the second leading cause of death in the US—was responsible for 38% of hospice admissions in 2013, whereas heart disease (including but not limited to HF)—the leading cause of death— was responsible for 13% of hospice admissions.14 The 2013 American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association guidelines for HF recommend consideration of hospice or palliative care for inpatient and transitional care.15 In future work, it would be important to better understand the drivers behind decisions around comfort care for patients hospitalized with HF.

With regards to the policy implications of our study, we found that on average, adjusting 30-day mortality rates for early comfort care was not associated with a change in hospital mortality rankings. For those hospitals with high comfort care rates, adjusting for comfort care did lower mortality rates, but the change was so small as to be clinically insignificant. CMS’ RSMR for HF excludes patients enrolled in hospice during the 12 months prior to index admission, including the first day of the index admission, acknowledging that death may not be an untoward outcome for such patients.16 Fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries excluded for hospice enrollment comprised 1.29% of HF admissions from July 2012 to June 201516 and are likely a subset of early comfort care patients in our sample, both because of the inclusiveness of chart review (vs claims-based identification) and because we defined early comfort care as comfort care initiated on day 0 or 1 of hospitalization. Nevertheless, with our data we cannot assess to what degree our findings were due solely to hospice patients excluded from CMS’ current estimates.

Prior research has described the underuse of palliative care among patients with HF17 and the association of palliative care with better patient and family experiences at the end of life.18-20 We add to this literature by describing the epidemiology—prevalence, changes over time, and associated factors—of early comfort care for HF in a national sample of hospitals. This serves as a baseline for future work on end-of-life care among patients hospitalized for HF. Our findings also contribute to ongoing discussion about how best to risk-adjust mortality metrics used to assess hospital quality in pay-for-performance programs. Recent research on stroke and pneumonia based on California data suggests that not accounting for do-not-resuscitate (DNR) status biases hospital mortality rates.21,22 Earlier research examined the impact of adjusting hospital mortality rates for DNR for a broader range of conditions.23,24 We expand this line of inquiry by examining the hospital-level association of early comfort care with mortality rates for HF, utilizing a national, contemporary cohort of inpatient stays. In addition, while studies have found that DNR rates within the first 24 hours of admission are relatively high (median 15.8% for pneumonia; 13.3% for stroke),21,22 comfort care is distinct from DNR.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of several potential limitations. First, we did not have any information about patient or family wishes regarding end-of-life care, or the exact timing of early comfort care (eg, day 0 or day 1). The initiation of comfort care usually follows conversations about end-of-life care involving a patient, his or her family, and the medical team. Thus, we do not know if low early comfort care rates represent the lack of such a conversation (and thus poor-quality care) or the desire by most patients not to initiate early comfort care (and thus high-quality care). This would be an important area for future research. Second, we included only patients admitted to hospitals that participate in GWTG-HF, a voluntary quality improvement initiative. This may limit the generalizability of our findings, but it is unclear how our sample might bias our findings. Hospitals engaged in quality improvement may be more likely to initiate early comfort care aligned with patients’ wishes; on the other hand, hospitals with advanced surgical capabilities are over-represented in our sample and these hospitals are less likely to initiate early comfort care. Third, we examined associations and cannot make conclusions about causality. Residual measured and unmeasured confounding may influence these findings.

In summary, we found that early comfort care rates for fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries admitted for HF varies widely among hospitals, but median rates of early comfort care have not changed over time. On average, there was no correlation between hospital-level, 30-day, RSMRs and rates of early comfort care. This suggests that current efforts to lower mortality rates have not had unintended consequences for hospitals that institute early comfort care more commonly than their peers.