Shorter Versus Longer Courses of Antibiotics for Infection in Hospitalized Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

BACKGROUND: Infection is a leading cause of hospitalization with high morbidity and mortality, but there are limited data to guide the duration of antibiotic therapy.

PURPOSE: Systematic review to compare outcomes of shorter versus longer antibiotic courses among hospitalized adults and adolescents.

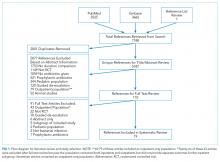

DATA SOURCES: MEDLINE and Embase databases, 1990-2017.

STUDY SELECTION: Inclusion criteria were human randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in English comparing a prespecified short course of antibiotics to a longer course for treatment of infection in hospitalized adults and adolescents aged 12 years and older.

DATA EXTRACTION: Two authors independently extracted study characteristics, methods of statistical analysis, outcomes, and risk of bias.

DATA SYNTHESIS: Of 5187 unique citations identified, 19 RCTs comprising 2867 patients met our inclusion criteria, including the following: 9 noninferiority trials, 1 superiority design trial, and 9 pilot studies. Across 13 studies evaluating 1727 patients, no significant difference in clinical efficacy was observed (d = 1.6% [95% confidence interval (CI), −1.0%-4.2%]). No significant difference was detected in microbiologic cure (8 studies, d = 1.2% [95% CI, −4.1%-6.4%]), short-term mortality (8 studies, d = 0.3% [95% CI, −1.2%-1.8%]), longer-term mortality (3 studies, d = −0.4% [95% CI, −6.3%-5.5%]), or recurrence (10 studies, d = 2.1% [95% CI, −1.2%-5.3%]). Heterogeneity across studies was not significant for any of the primary outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS: Based on the available literature, shorter courses of antibiotics can be safely utilized in hospitalized patients with common infections, including pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and intra-abdominal infection, to achieve clinical and microbiologic resolution without adverse effects on mortality or recurrence.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Study Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

Our primary outcomes were clinical cure, microbiologic cure, mortality, and infection recurrence. Secondary outcomes were secondary MDR infection, cost, and length of stay (LOS). We conducted all analyses with Stata MP version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). For each outcome, we reported the difference (95% confidence interval [CI]) between treatment arms as the rate in the short course arm minus the rate in the long course arm, consistent with the typical presentation of noninferiority data. When not reported in a study, we calculated risk difference and 95% CI using reported patient-level data. Positive values for risk difference favor the short course arm for favorable outcomes (ie, clinical and microbiologic cure) and the long course arm for adverse outcomes (ie, mortality and recurrence). A meta-analysis was used to pool risk differences across all studies for primary outcomes and for clinical cure in the community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) subgroup. We also present results as odds ratios and risk ratios in the online supplement. All meta-analyses used random effects models, as described by DerSimonian and Laird,27,28 with variance estimates of heterogeneity taken from the Mantel-Haenszel fixed effects model. We investigated heterogeneity between studies using the χ2 I2 statistic. We considered a P < .1 to indicate statistically significant heterogeneity and classified heterogeneity as low, moderate, or high on the basis of an I2 of 25%, 50%, or 75%, respectively. We used funnel plots to assess for publication bias.

RESULTS

Search Results

Characteristics of Included Studies

Common study outcomes included clinical cure or efficacy (composite of symptom cure and improvement; n = 13), infection recurrence (n = 10), mortality (n = 9), microbiologic cure (n = 8), and LOS (n = 7; supplementary Table 1).

Nine studies were pilot studies, 1 was a traditional superiority design study, and 9 were noninferiority studies with a prespecified limit of equivalence of either 10% (n = 7) or 15% (n = 2).

Clinical Cure and Efficacy

Nine studies of 1225 patients evaluated clinical cure and efficacy in CAP (supplementary Figure 1).29,35,38-40,44-47 The overall risk difference was d = 2.4% (95% CI, −0.7%-5.5%). There was no heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 0%, P = .45).

Microbiologic Cure

Eight studies of 366 patients evaluated microbiologic cure (supplementary Figure 2).32-34,36,38,40,41,47 The overall risk difference was d = 1.2% (95% CI, −4.1%-6.4%). There was no statistically significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 13.3%, P = .33).

Mortality

Eight studies of 1740 patients evaluated short-term mortality (in hospital to 45 days; Figure 2),30-32,37,39,41,43 while 3 studies of 654 patients evaluated longer-term mortality (60 to 180 days; supplementary Figure 3).30,31,33 The overall risk difference was d = 0.3% (95% CI, −1.2%-1.8%) for short-term mortality and d = −0.4% (95% CI, −6.3%-5.5%) for longer-term mortality. There was no heterogeneity between studies for either short-term (I2 = 0.0%, P = .66) or longer-term mortality (I2 = 0.0%, P = .69).

Infection Recurrence

Ten studies of 1554 patients evaluated infection recurrence (Figure 2).30-34,40-42,45,46 The overall risk difference was d = 2.1% (95% CI, −1.2%-5.3%). There was no statistically significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 21.0%, P = .25). Two of the 3 studies with noninferiority design (both evaluating intra-abdominal infections) met their prespecified margins.41,42 In Chastre et al.,31 the overall population (d = 3.0%; 95% CI, −5.8%-11.7%) and the subgroup with VAP due to nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli (NF-GNB; d = 15.2%; 95% CI, −0.9%-31.4%) failed to meet the 10% noninferiority margin.