Implementation of a Process for Initiating Naltrexone in Patients Hospitalized for Alcohol Detoxification or Withdrawal

BACKGROUND: Naltrexone trials have demonstrated improved outcomes for patients with alcohol use disorders. Hospital initiation of naltrexone has had limited study.

OBJECTIVES: To describe the implementation and impact of a process for counseling hospitalized patients with alcohol withdrawal about naltrexone.

DESIGN: A pre-post study analysis.

SETTING: A tertiary academic center.

PATIENTS: Patients hospitalized for alcohol withdrawal.

INTERVENTIONS: (1) Provider education about the efficacy and contraindications of naltrexone and (2) algorithms for evaluating patients for naltrexone.

MEASUREMENTS: The percentages of patients counseled about and prescribed naltrexone before discharge and the percentages of pre- and postintervention patients with 30-day emergency department (ED) revisits and rehospitalizations.

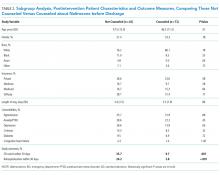

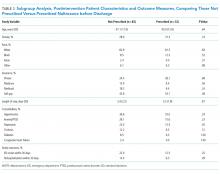

RESULTS: We identified 128 patient encounters before and 114 after implementation. The percentage of patients counseled about naltrexone rose from 1.6% preimplementation to 63.2% postimplementation (P < .001); the percentage of patients prescribed naltrexone rose from 1.6% to 28.1% (P < .001). Comparing preintervention versus postintervention groups, there were no unadjusted differences in 30-day ED revisits (25.8% vs 19.3%; P = .23) or rehospitalizations (10.2% vs 11.4%; P = .75). When adjusted for demographics and comorbidities, postintervention patients had lower odds of 30-day ED revisits (odds ratio [OR] = 0.47; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.24-0.94) but no significant difference in rehospitalizations (OR = 0.76; 95% CI, 0.30-1.92). In subgroup analysis, postintervention patients counseled versus those not counseled about naltrexone were less likely to have 30-day ED revisits (9.7% vs 35.7%; P = .001) and rehospitalizations (2.8% vs 26.2%; P < .001).

CONCLUSIONS: The implementation of a process for counseling patients hospitalized for alcohol withdrawal about using naltrexone for the maintenance of sobriety was associated with lower 30-day ED revisits but no statistically significant difference in rehospitalizations.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

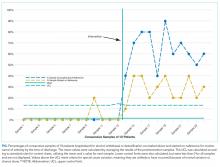

For 2 process measures, the percentages of patients counseled about and started on naltrexone, we plotted consecutive samples of 10 patients before and after intervention on a control chart, using preintervention data to calculate means and control limits.

Subgroup Analysis

We used multivariate logistic regression to evaluate the associations between counseling versus no counseling and prescription of naltrexone versus no prescription for study outcomes in the postintervention subgroup, adjusting for age, gender, race, insurance type, and medical comorbidities.

RESULTS

Patients

We identified 188 preimplementation encounters and excluded 12 patients (6.4%) for primary admission reasons other than alcohol withdrawal or detoxification and 48 (25.5%) repeat hospitalizations, leaving 128 unique patient encounters. We identified 166 postimplementation encounters and excluded 25 (15.1%) hospitalizations for admission reason and 27 repeat hospitalizations (16.3%), leaving 114 unique patient encounters (flow diagram in supplemental Appendix 3). The most common admission reason for the exclusion of encounters was withdrawal from a substance other than alcohol (supplemental Appendix 4). The percentages of encounters excluded in preimplementation and postimplementation periods were similar at 31.9% and 31.4%, respectively.

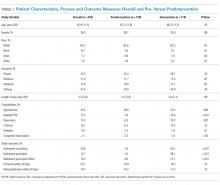

The majority of patients were male and white, and almost half were uninsured (Table 1). There were no demographic differences between patients in the pre- versus postimplementation groups. For studied comorbidities, postintervention patients were more likely to have hypertension, anxiety, and depression.

Process Measures

Among those counseled about naltrexone before discharge, 34 of 74 patients (45.9%) had no contraindications to naltrexone and were interested in taking the medication. Among the 40 patients who were counseled about but not prescribed naltrexone, 19 (47.5%) declined, 9 (22.5%) had liver function tests elevated more than 3 times the upper limit of the reference range, 9 (22.5%) had concurrent opiate use, and 3 (7.5%) had multiple contraindications.

Among the 34 patients who were prescribed naltrexone, 25 (73.5%) filled at least 1 prescription as confirmed by phone call to the relevant pharmacy.

Outcome Measures

Subgroup Analysis

Balancing Measure

The mean length of stay for all patient encounters was 3.3 days. There were no differences in length of stay comparing pre- with postintervention patient encounters (Table 1) or those postintervention patients counseled versus not counseled (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that counseling about medications for the maintenance of sobriety can be implemented as part of the routine care of hospitalized patients with AUDs. In our experience, about half of the patients counseled had no contraindications to naltrexone and were willing to take it at discharge. Almost three-fourths of those who were prescribed naltrexone filled the prescription at least once. The counseling process was not associated with increased length of stay. In the adjusted analysis, postintervention patients had significantly lower odds of 30-day ED returns. Additionally, in subgroup analysis, postintervention patients counseled about naltrexone had significantly lower rates of subsequent healthcare utilization compared with those not counseled, with absolute differences of 26% for ED revisits and 22% for rehospitalizations within 30 days.

The failure to demonstrate a difference in adjusted rehospitalization rates in the postintervention versus the preintervention group has several possible explanations. First, we had incomplete fidelity to our interventions, documenting counseling about naltrexone before discharge in over 60% of postintervention patients, raising the possibility that better fidelity may have resulted in improved outcomes. Related to this, only 28% of postintervention patients were prescribed naltrexone, which may be an inadequate sample size to demonstrate positive effects from the medication. Another possible explanation is that the postintervention group had higher rates of some of the comorbidities we assessed, namely, anxiety, depression, and hypertension, which could have negatively impacted the effectiveness of the interventions to prevent rehospitalization; however, after adjusting for comorbidities, the odds of rehospitalization were still not significantly different. It is interesting that the odds of postintervention ED revisits (but not rehospitalizations) were lower in the adjusted analysis. It may be that patients who revisit the ED and are not rehospitalized are different in important ways from those who are readmitted. Alternately, the larger number of ED revisits overall (about twice the rate of rehospitalization) may have made it easier to identify positive effects from the intervention for this outcome than rehospitalization (ie, the study may have been underpowered to detect a relatively small reduction in rehospitalization). It is also possible, however, that the interventions were simply insufficient to prevent rehospitalization.

The subgroup analysis, however, did find significant differences in both outcome measures for postintervention patients counseled versus not counseled about naltrexone before discharge. There are several possible explanations for these results. First, there may have been unmeasured differences in those counseled versus not counseled that explain the reductions observed in subsequent healthcare utilization. For example, the counseled patients could have been more motivated to change and, thus, more readily approached by providers for counseling. The lack of any demographic differences between the 2 groups and the relative simplicity of the counseling part of the intervention occurring as part of daily rounds argue against this hypothesis, but there are many potential unmeasured confounders (eg, homelessness, ability to afford medications), and this possibility remains. A second possible explanation is that patients counseled about naltrexone could have been more likely than those not counseled to seek subsequent care at other institutions. A third possibility is that that the counseling about (and prescribing when appropriate) naltrexone itself led to the observed decreases in subsequent ED visits and hospitalizations. This hypothesis would have been more supported had we been able to demonstrate a statistically significant reduction in healthcare utilization in those prescribed versus not prescribed naltrexone. But there were nonsignificant trends in the reduction of ED revisits and rehospitalizations among those prescribed the medication, suggesting we may have been able to demonstrate statistically significant reductions with a larger sample size.

Comparing our results with existing literature is challenging. The majority of randomized trials of naltrexone for AUDs were conducted in the outpatient setting.3-10 Most of these trials utilized some type of psychosocial intervention in addition to naltrexone.3-5,8-10 The 1 prior naltrexone study we identified conducted in the inpatient setting by Wei et al.14 is the most similar to our study. The authors reported the effects of a new process for assessing hospitalized patients with AUDs, including the use of a discharge planning tool for all patients admitted with alcohol dependence. The discharge tool included prompts for naltrexone in appropriate patients. The measured outcomes included the percentage of eligible patients prescribed naltrexone at discharge and the percentages of ED revisits and rehospitalizations within 30 days. Postintervention, 64% of eligible patients were prescribed naltrexone compared with 0% before, very similar to our results. There were significant decreases among all discharged patients with alcohol dependence for 30-day ED revisits (18.8% pre- vs 6.1% postimplementation) and rehospitalizations (23.4% vs 8.2%). The study differed from ours in a number of important respects, including a location in a large urban setting and implementation on a teaching service rather than an attending-only hospitalist service. Additionally, the authors studied 1 month of process implementation and compared it to another month 1 year before the new process, with an overall smaller sample size of 64 patients before and 49 patients after implementation. Potential reasons why Wei et al.14 were able to document lower rehospitalization rates postintervention when we did not include the differences in patient population (eg, high homeless rate, lower percentage of female patients in Wei study) and secular trends unrelated to interventions in either study.

Limitations of our study include the nonrandomized and uncontrolled design, which introduces the possibility of unmeasured confounding factors leading to the decrease we observed in healthcare utilization. Additionally, the single-center design precludes our ability to assess for healthcare utilization outcomes in other nearby facilities. We had incomplete implementation of our new process, counseling just over 60% of patients. As our primary outcomes relied on documentation in the medical record, both undersampling (not documenting some interventions) and reporting bias (being more likely to record positive sessions from intervention) are possible. Lastly, despite a moderate total sample size of almost 250 patients, the relatively small numbers of patients who were actually prescribed naltrexone in our study lessens our ability to show direct impact.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates a practical process for counseling about and prescribing naltrexone to patients hospitalized for alcohol detoxification or withdrawal. We demonstrate that many of these patients will be interested in starting naltrexone at discharge and will reliably fill the prescriptions if written. Counseling was associated with a significant reduction in subsequent healthcare utilization. These results have a wide potential impact given the ubiquitous nature of AUDs among hospitalized patients in community and academic settings.