Periprocedural Bridging Anticoagulation

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

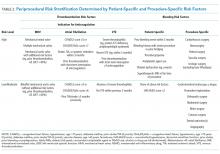

Nevertheless, many surgical and invasive procedures do warrant OAC interruption due to the inherent bleeding risk of the procedure or other logistical considerations. Procedures associated with an increased bleeding risk include urologic surgery (except laser lithotripsy), surgery on highly vascular organs (eg, kidney, liver, spleen), bowel resection, cardiac surgery, and intracranial or spinal surgery.7 Alternatively, some procedures with acceptably low bleeding risk (eg, colonoscopy) are routinely performed during an OAC interruption due to the fact that a high bleeding risk intervention may be necessary during the procedure (eg, polypectomy). This approach may be preferable when a significant amount of preparation is required (eg, bowel preparation) and may be a more efficient use of healthcare resources by avoiding repeat procedures.

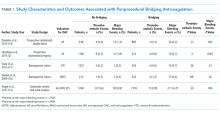

Bridging Anticoagulation Does Not Significantly Reduce Thromboembolic Events

BRIDGE was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial among patients with atrial fibrillation (n = 1884) requiring OAC interruption for mostly low-risk, ambulatory surgeries or invasive procedures (eg, gastrointestinal endoscopy, cardiac catheterization). Notably, thromboembolism events were rare, and there was no significant difference in thromboembolism events between patients randomized to placebo or bridging with LMWH (0.4% vs 0.3%, respectively; P = .73).14 However, the proportion of patients enrolled with the highest thromboembolic risk (ie, CHADS2 score 5-6 or prior transient ischemic attack and/or stroke) was low, potentially indicating an underestimated benefit in these patients. Major bleeding was significantly reduced in patients forgoing bridging anticoagulation (1.3% vs 3.2%; RR 0.41; 95% confidence interval, 0.20-0.78; P = .005), although bleeding occurred more frequently than thromboembolism in both groups.

Even though randomized trials assessing the safety and efficacy of bridging for VTE or MHVs have not been completed, evidence is not entirely lacking.16,17 A rigorous observational study limited to a VTE cohort (deep vein thrombosis of upper or lower extremity and/or pulmonary embolism) analyzed the effects of bridging in patients with a surgical or invasive procedure-related OAC interruption. Patients were stratified according to the American College of Chest Physicians perioperative guideline risk-stratification schema, and most VTE events (≥93%) occurred more than 12 months prior to OAC interruption.7 Importantly, the study found a nonsignificant difference in thromboembolism events between patients who were bridged and those who were not (0.0% vs 0.2%, respectively; P = .56), a very low overall thromboembolism event rate (0.2%), and a lack of correlation between events and risk-stratification category.17 In other words, all thromboembolic events occurred in the low- and moderate-risk groups, which include patients who do not warrant bridging under current guidelines. Clinically relevant bleeding occurred in 17 (0.9%) of 1812 patients studied. Notably, 15 (2.7%) of 555 patients receiving bridging suffered clinically relevant bleeding as compared with 2 (0.2%) of 1257 patients forgoing bridging anticoagulation.

The Bleeding Risk of Bridging Anticoagulation Often Outweighs the Potential Benefits

The early observational studies on LMWH bridging demonstrated that thromboembolic events are infrequent (0.4%-0.9%), whereas major bleeding events occur up to 7 times more often (0.7%-6.7%).10-12 The BRIDGE trial demonstrated comparably low thromboembolic events (0.3%). In the patients treated with bridging LMWH, major bleeding (3.2%) occurred 10 times more frequently than thromboembolism.14 Likewise, in a VTE cohort study, Clark et al.17 demonstrated “a 17-fold higher risk of bleeding without a significant difference in the rate of recurrent VTE” in patients bridged with heparin as compared with those who were not. Considering that recurrent VTE and major bleeding events have similar case-fatality rates,18 these increases in major bleeding events without reductions in thromboembolic events unmistakably tip the risk–benefit balance sharply towards an increased risk of harm.