A Prescription for Note Bloat: An Effective Progress Note Template

BACKGROUND: United States hospitals have widely adopted electronic health records (EHRs). Despite the potential for EHRs to increase efficiency, there is concern that documentation quality has suffered.

OBJECTIVE: To examine the impact of an educational session bundled with a progress note template on note quality, length, and timeliness.

DESIGN: A multicenter, nonrandomized prospective trial.

SETTING: Four academic hospitals across the United States.

PARTICIPANTS: Intern physicians on inpatient internal medicine rotations at participating hospitals.

INTERVENTION: A task force delivered a lecture on current issues with documentation and suggested that interns use a newly designed best practice progress note template when writing daily progress notes.

MEASUREMENTS: Note quality was rated using a tool designed by the task force comprising a general impression score, the validated Physician Documentation Quality Instrument, 9-item version (PDQI-9), and a competency questionnaire. Reviewers documented number of lines per note and time signed.

RESULTS: Two hundred preintervention and 199 postintervention notes were collected. Seventy percent of postintervention notes used the template. Significant improvements were seen in the general impression score, all domains of the PDQI-9, and multiple competency items, including documentation of only relevant data, discussion of a discharge plan, and being concise while adequately complete. Notes had approximately 25% fewer lines and were signed on average 1.3 hours earlier in the day.

CONCLUSIONS: The bundled intervention for progress notes significantly improved the quality, decreased the length, and resulted in earlier note completion across 4 academic medical centers.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Graders were internal medicine teaching faculty involved in the study and were assigned to review notes from their respective sites by directly utilizing the EHR. Although this introduces potential for bias, it was felt that many of the grading elements required the grader to know details of the patient that would not be captured if the note was removed from the context of the EHR. Additionally, graders documented note length (number of lines of text), the time signed by the housestaff, and whether the template was used. Three different graders independently evaluated each note and submitted ratings by using Research Electronic Data Capture.13

Statistical Analysis

Means for each item on the grading tool were computed across raters for each progress note. These were summarized by institution as well as by pre- and postintervention. Cumulative logit mixed effects models were used to compare item responses between study conditions. The number of lines per note before and after the note template intervention was compared by using a mixed effects negative binomial regression model. The timestamp on each note, representing the time of day the note was signed, was compared pre- and postintervention by using a linear mixed effects model. All models included random note and rater effects, and fixed institution and intervention period effects, as well as their interaction. Inter-rater reliability of the grading tool was assessed by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) using the estimated variance components. Data obtained from the PDQI-9 portion were analyzed by individual components as well as by sum score combining each component. The sum score was used to generate odds ratios to assess the likelihood that postintervention notes that used the template compared to those that did not would increase PDQI-9 sum scores. Both cumulative and site-specific data were analyzed. P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

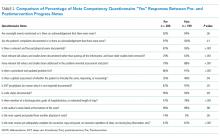

The mean general impression score significantly improved from 2.0 to 2.3 (on a 1-3 scale in which 2 is average) after the intervention (P < .001). Additionally, note quality significantly improved across each domain of the PDQI-9 (P < .001 for all domains, Table 1). The ICC was 0.245 for the general impression score and 0.143 for the PDQI-9 sum score.

Three of 4 institutions documented the number of lines per note and the time the note was signed by the intern. Mean number of lines per note decreased by 25% (361 lines preintervention, 265 lines postintervention, P < .001). Mean time signed was approximately 1 hour and 15 minutes earlier in the day (3:27

Site-specific data revealed variation between sites. Template use was 92% at UCSF, 90% at UCLA, 79% at Iowa, and 21% at UCSD. The mean general impression score significantly improved at UCSF, UCLA, and UCSD, but not at Iowa. The PDQI-9 score improved across all domains at UCSF and UCLA, 2 domains at UCSD, and 0 domains at Iowa. Documentation of pertinent labs and studies significantly improved at UCSF, UCLA, and Iowa, but not UCSD. Note length decreased at UCSF and UCLA, but not at UCSD. Notes were signed earlier at UCLA and UCSD, but not at UCSF.

When comparing postintervention notes based on template use, notes that used the template were significantly more likely to receive a higher mean impression score (odds ratio [OR] 11.95, P < .001), higher PDQI-9 sum score (OR 3.05, P < .001), be approximately 25% shorter (326 lines vs 239 lines, P < .001), and be completed approximately 1 hour and 20 minutes earlier (3:07