Transitioning from General Pediatric to Adult-Oriented Inpatient Care: National Survey of US Children’s Hospitals

BACKGROUND: Hospital charges and lengths of stay may be greater when adults with chronic conditions are admitted to children’s hospitals. Despite multiple efforts to improve pediatric-adult healthcare transitions, little guidance exists for transitioning inpatient care.

OBJECTIVE: This study sought to characterize pediatric-adult inpatient care transitions across general pediatric services at US children’s hospitals.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS: National survey of inpatient general pediatric service leaders at US children’s hospitals from January 2016 to July 2016.

MEASUREMENTS: Questionnaires assessed institutional characteristics, presence of inpatient transition initiatives (having specific process and/or leader), and 22 inpatient transition activities. Scales of highly correlated activities were created using exploratory factor analysis. Logistic regression identified associations between institutional characteristics, transition activities, and presence of an inpatient transition initiative.

RESULTS: Ninety-six of 195 children’s hospitals responded (49.2% response rate). Transition initiatives were present at 38% of children’s hospitals, more often when there were dual-trained internal medicine–pediatrics providers or outpatient transition processes. Specific activities were infrequent and varied widely from 2.1% (systems to track youth in transition) to 40.5% (addressing potential insurance problems). Institutions with initiatives more often consistently performed the majority of activities, including using checklists and creating patient-centered transition care plans. Of remaining activities, half involved transition planning, the essential step between readiness and transfer.

CONCLUSIONS: Relatively few inpatient general pediatric services at US children’s hospitals have leaders or dedicated processes to shepherd transitions to adult-oriented inpatient care. Across institutions, there is a wide variability in performance of activities to facilitate this transition. Feasible process and outcome measures are needed.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Institutional Context and Factors Influencing Inpatient Transitions

The following hospital characteristics were assessed: administrative structure (free-standing, hospital-within-hospital, or “free-leaning,” ie, separate physical structure but same administrative structure as a general hospital), urban versus rural, academic versus nonacademic, presence of an inpatient adolescent unit, presence of subspecialty admitting services, and providers with med–peds or family medicine training. The following provider group characteristics were assessed: number of full-time equivalents (FTEs), scope of practice (inpatient only, combination inpatient/outpatient), proportion of providers at a “senior” level (ie, at least 7 years posttraining or at an associate professor rank), estimated number of discharges per week, and proportion of patients cared for without resident physicians.

Inpatient Transition Initiative

Each institution was categorized as having or not having an inpatient transition initiative by whether they indicated having either (1) an institutional leader of the transition from pediatric to adult-oriented inpatient settings or (2) an inpatient transition process, for which “process” was defined as “a standard, organized, and predictable set of transition activities that may or may not be documented, but the steps are generally agreed upon.”

Specific Inpatient Transition Activities

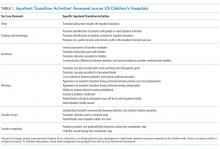

Respondents indicated whether 22 activities occurred consistently, defined as at least 50% of the time. To facilitate description, activities were grouped into categories using the labels from the Six Core Elements framework3 (Table 1): Policy, Tracking and Monitoring, Readiness, Planning, Transfer of Care, and Transfer Completion. Respondents were also asked whether outpatient pediatric-adult transition activities existed at their institution and whether they were linked to inpatient transition activities.

Data Collection

After verifying contact information, respondents received an advanced priming phone call followed by a mailed request to participate with a printed uniform resource locator (URL) to the web survey. Two email reminders containing the URL were sent to nonresponders at 5 and 10 days after the initial mailing. Remaining nonresponders then received a reminder phone call, followed by a mailed paper copy of the survey questionnaire to be completed by hand approximately 2 weeks after the last emailed request. The survey was administered using the Qualtrics web survey platform (www.qualtrics.com). Data collection occurred between January 2016 and July 2016. Participants received a $20 incentive.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics summarized the current state of inpatient transition at general pediatrics services across US children’s hospitals. Exploratory factor analysis assessed whether individual activities were sufficiently correlated to allow grouping items and constructing scales. Differences in institutional or respondent characteristics between hospitals that did and did not report having an inpatient initiative were compared using t tests for continuous data. Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical data because some cell sizes were ≤5. Bivariate logistic regression quantified associations between presence versus absence of specific transition activities and presence versus absence of an inpatient transition initiative. Analyses were completed in STATA (SE version 14.0; StataCorp, College Station, Texas). The institutional review board at our institution approved this study.

RESULTS

Responses were received from 96 of 195 children’s hospitals (49.2% response rate). Responding institution characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Free-standing children’s hospitals made up just over one-third of the sample (36%), while the remaining were free-leaning (22%) or hospital-within-hospital (43%). Most children’s hospitals (58%) did not have a specific adult-oriented hospital identified to receive transitioning patients. Slightly more than 10% had an inpatient adolescent unit. The majority of institutions were academic medical centers (78%) in urban locations (88%). Respondents represented small (<5 FTE, 21%), medium (6-10 FTE, 36%), and large provider groups (11+ FTE, 44%). Although 70% of respondents described their groups as “hospitalist only,” meaning providers only practiced inpatient general pediatrics, nearly 30% had providers practicing inpatient and outpatient general pediatrics. Just over 40% of respondents reported having med–peds providers. Pediatric-adult transition processes for outpatient care were present at 45% of institutions.

Transition Activities

Thirty-eight percent of children’s hospitals had an inpatient transition initiative using our study definition—31% by having a set of generally agreed upon activities, 19% by having a leader, and 11% having both. Inpatient transition leaders included pediatric hospitalists (43%), pediatric subspecialists and primary care providers (14% each), med–peds providers (11%), or case managers (7%). Respondent and institutional characteristics were similar at institutions that did and did not have an inpatient transition initiative (Table 2); however, children’s hospitals with inpatient transition initiatives more often had med–peds providers (P = .04). Institutions with pediatric-adult outpatient care transition processes more often had an inpatient initiative (71% and 29%, respectively; P = .001).

Exploratory factor analysis identified 2 groups of well-correlated items, which we grouped into “preparation” and “transfer initiation” scales (supplementary Appendix). The preparation scale was composed of the following 5 items (Cronbach α = 0.84): proactive identification of patients anticipated to need transition, proactive identification of patients overdue for transition, readiness formally assessed, timing discussed with family, and patient and/or family informed that the next stay would be at the adult facility. The transfer initiation scale comprised the following 6 items (Cronbach α = 0.72): transition education provided to families, primary care–subspecialist agreement on timing, subspecialist–subspecialist agreement on timing, patient decision-making ability established, adult facility tour, and standardized handoff communication between healthcare providers. While these items were analyzed only in this scale, other activities were analyzed as independent variables. In this analysis, 40.9% of institutions had a preparation scale score of 0 (no items performed), while 13% had all 5 items performed. Transfer initiation scale scores ranged from 0 (47%) to 6 (2%).

Specific activities varied widely across institutions, and none of the activities occurred at a majority of children’s hospitals (Table 3). Only 11% of children’s hospital transition policies referenced transitions of inpatient care. The activity most commonly reported across children’s hospitals was addressing potential insurance problems (41%). The least common inpatient transition activities were having child life consult during the first adult hospital stay (6%) or having a system to track and monitor youth in the inpatient transition process (2%). Transition processes and policies were relatively new among institutions that had them—average years an inpatient transition process had been in place was 1.2 (SD 0.4), and average years with a transition policy, including inpatient care, was 1.3 (SD 0.4).