Near and Far

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Her antinuclear antibody titer was >1:1280 (normal: <80). Anti-SSA and -SSB antibodies were both positive, with a titer >100 (normal: <20). Rheumatoid factor was positive at 22 IU/mL (normal: 0-14). Anti-smith, anti-double stranded DNA, and anti-ribonucleoprotein antibodies were negative.

Sjögren’s syndrome appears to be the ultimate etiology of this patient’s distal RTA. The diagnosis of Sjögren’s is more classically made in the presence of lacrimal and/or salivary dysfunction and confirmed with compatible autoantibodies. In the absence of dry eyes or dry mouth, attention should be focused on her skin findings. Cutaneous vasculitis does occur in a small percentage of Sjögren’s syndrome cases. Urticarial lesions have been reported in this subset, and skin biopsy would further support the diagnosis.

Treatment of Sjögren’s syndrome with immunosuppressive therapy may ameliorate renal parenchymal pathology and improve her profound metabolic disturbances.

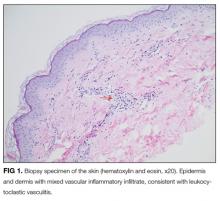

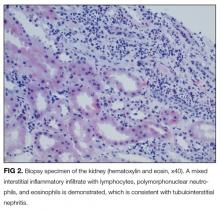

On further questioning, she described several months of mild xerostomia, which resulted in increased consumption of fluids. She did not have keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Biopsy of her urticarial rash demonstrated a leukocytoclastic vasculitis with eosinophilic infiltration (Figure 1). Renal biopsy with hematoxylin and eosin staining, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy demonstrated an immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis and moderate tubulointerstitial nephritis (Figure 2). A diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome was made based on the patient’s xerostomia, high titers of antinuclear antibodies, SSA and SSB antibodies, positive rheumatoid factor, hypocomplementemia, and systemic manifestations associated with Sjögren’s syndrome, including distal RTA, nephrolithiasis, and hives, with histologic evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

She received aggressive potassium and bicarbonate repletion and, several days later, had normalization of both. Her weakness and myalgia rapidly improved concomitantly with the correction of her hypokalemia. Five days later she was ambulating independently and discharged with potassium citrate and prednisone therapy. She had improved fatigue and rash at a 1-month follow-up with rheumatology. As an outpatient, she was started on azathioprine and slowly tapered off her steroids. Over the next several months, she had normal potassium, bicarbonate, and renal function, although she did require lithotripsy for an obstructive renal stone.

COMMENTARY

RTA should be considered in the differential diagnosis of an unexplained normal anion gap metabolic acidosis. There are 3 major types of RTAs, with different characteristics. In type 1 (distal) RTA, the primary defect is impaired distal acidification of the urine. Distal RTA commonly presents with hypokalemia, calciuria (often presenting as renal stones), and a positive UAG.1 In type 2 (proximal) RTA, the primary defect is impaired bicarbonate reabsorption, leading to bicarbonate wasting in the urine. Proximal RTAs can be secondary to an isolated defect in bicarbonate reabsorption or generalized proximal renal tubule dysfunction (Fanconi syndrome).1 A type 4 RTA is characterized by hypoaldosteronism, presenting usually with a mild nonanion gap metabolic acidosis and hyperkalemia. This patient’s history of renal stones, hypokalemia, and positive UAG supported a type 1 (distal) RTA. Distal RTA is often idiopathic, but initial evaluation should include a review of medications and investigation into an underlying systemic disorder (eg, plasma cell dyscrasia or autoimmune disease). This would include eliciting a possible history of xerostomia and xerophthalmia, together with testing of SSA (Ro) and SSB (La) antibodies, to assess for Sjögren’s syndrome. In addition, checking serum calcium to assess for hyperparathyroidism or familial idiopathic hypercalciuria and a review of medications, such as lithium and amphotericin,1 may uncover other secondary causes of distal RTA.

While Sjögren’s syndrome primarily affects salivary and lacrimal glands, leading to dry mouth and dry eyes, respectively, extraglandular manifestations are common, with fatigue and arthralgia occurring in half of patients. Extra-glandular involvement also often includes the skin and kidneys but can affect several other organ systems, including the central nervous system, heart, lungs, bone marrow, and lymph nodes.2

There are many cutaneous manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome.3 Xerosis, or xeroderma, is the most common and is characterized by dry, scaly skin. Cutaneous vasculitis can occur in 10% of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome and often presents with palpable purpura or diffuse urticarial lesions, as in our patient.4 Erythematous maculopapules and cryoglobulinemic vasculitis may also occur.4 A less common skin manifestation is annular erythema, presenting as an indurated, ring-like lesion.5

Chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis is the most common renal manifestation of Sjögren’s syndrome.6 This often pre-sents with a mild elevated serum creatinine and a distal RTA, leading to hypokalemia, as in the case discussed. Distal RTA is well described, occurring in one-quarter of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome.7 The pathophysiology leading to distal RTA in Sjögren’s syndrome is thought to arise from autoimmune injury to the H(+)-ATPase pump in the renal collecting tubules, leading to decreased distal proton secretion.8,9 Younger adults with Sjögren’s syndrome, in the third and fourth decades of life, have a predilection to develop tubulointerstitial inflammation, distal RTA, and nephrolithiasis, as in the present case.6 Sjögren’s syndrome less commonly presents with membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis or membranous nephropathy.10,11 Cryoglobulinemia-associated hypocomplementemia and glomerulonephritis may also occur with Sjögren’s syndrome, yet glomerular lesions are less common than is tubulointerstitial inflammation. The patient discussed had proteinuria and evidence of immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis.

Treatment of sicca symptoms is generally supportive. It includes artificial tears, encouragement of good hydration, salivary stimulants, and maintaining good oral hygiene. Pilocarpine, a cholinergic parasympathomimetic agent, is approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat dry mouth associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. The treatment of extraglandular manifestations depends on the organ(s) involved. More severe presentations, such as vasculitis and glomerulonephritis, often require immunosuppressive therapy with systemic glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, or other immunosuppressive agents,12 including rituximab. RTA often necessitates treatment with oral bicarbonate and supplemental potassium repletion.

The base rate of disease (ie, prevalence of disease) influences a diagnostician’s pretest probability of a given diagnosis. The discussant briefly considered rare causes of hives (eg, vasculitis) but appropriately fine-tuned their differential for the patient’s hypokalemia and RTA. Once the diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome was made with certainty, the clinician was able to revisit the patient’s rash with a new lens. Urticarial vasculitis suddenly became a plausible consideration, despite its rarity (compared to allergic causes of hives) because of the direct link to the underlying autoimmune condition, which affected both the proximal muscles and distal nephrons.