Inpatient Portals for Hospitalized Patients and Caregivers: A Systematic Review

Patient portals, web-based personal health records linked to electronic health records (EHRs), provide patients access to their healthcare information and facilitate communication with providers. Growing evidence supports portal use in ambulatory settings; however, only recently have portals been used with hospitalized patients. Our objective was to review the literature evaluating the design, use, and impact of inpatient portals, which are patient portals designed to give hospitalized patients and caregivers inpatient EHR clinical information for the purpose of engaging them in hospital care. Literature was reviewed from 2006 to 2017 in PubMed, Web of Science, CINALPlus, Cochrane, and Scopus to identify English language studies evaluating patient portals, engagement, and inpatient care. Data were analyzed considering the following 3 themes: inpatient portal design, use and usability, and impact. Of 731 studies, 17 were included, 9 of which were published after 2015. Most studies were qualitative with small samples focusing on inpatient portal design; 1 nonrandomized trial was identified. Studies described hospitalized patients’ and caregivers’ information needs and design recommendations. Most patient and caregiver participants in included studies were interested in using an inpatient portal, used it when offered, and found it easy to use and/or useful. Evidence supporting the role of inpatient portals in improving patient and caregiver engagement, knowledge, communication, and care quality and safety is limited. Included studies indicated providers had concerns about using inpatient portals; however, the extent to which these concerns have been realized remains unclear. Inpatient portal research is emerging. Further investigation is needed to optimally design inpatient portals to maximize potential benefits for hospitalized patients and caregivers while minimizing unintended consequences for healthcare teams.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

RESULTS

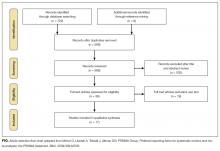

Of the 731 studies identified through database searching and reference review, 36 were included for full-text review and 17 met inclusion criteria (Figure; Table 1). Studies excluded after full-text review described portal use outside of the inpatient setting, portals not linked to hospital EHR clinical data, portals not designed for inpatients, and/or inpatient technology in general. The inpatient portal platforms, hardware used, and functionalities varied within included studies (Table 2). The majority of studies used custom, web-based inpatient portal applications on tablet computers. Most provided information about the patients’ hospital medications, healthcare team, and education about their condition and/or a medical glossary. Many included the patient’s schedule, hospital problem list, discharge information, and a way to keep notes.

There has been a recent increase in inpatient portal study publication, with 9 studies published during or after 2016. Five were conducted in the pediatric setting and all but 130 with English-speaking participants. Twelve studies were qualitative, many of which were conducted in multiple phases by using semi-structured interviews and/or focus groups to develop or redesign inpatient portals. Of the remaining studies, 3 used a cross-sectional design, 1 used a before and after design without a control group, and 1 was a nonrandomized trial. Studies were rated as having medium-to-high risk of bias because of design flaws (Table 1 in supplementary Appendix). Because many studies were small pilot studies and all were single-centered studies, the generalizability of findings to different healthcare settings or patient populations is limited.

Inpatient Portal Design

Most included studies evaluated patient and/or caregiver information needs to design and/or enhance inpatient portals.16,24-37 In 1 study, patients described an overall lack of information provided in the hospital and insufficient time to understand and remember information, which, when shared, was often presented by using medical terminology.30 They wanted information to help them understand their daily hospital routine, confirm and compare medications and test results, learn about care, and prepare for discharge. Participants in multiple studies echoed these results, indicating the need for a schedule of upcoming clinical events (eg, medication administration, procedures, imaging), secure and timely clinical information (eg, list of diagnoses and medications, test results), personalized education, a medical glossary, discharge information, and a way to take notes and recognize and communicate with providers.

Patients also requested further information transparency,34,37 including physicians’ notes, radiology results, operative reports, and billing information, along with general hospital information,16 meal ordering,33 and video conferencing.27 ln designing and refining an inpatient medication-tracking tool, participants identified the need for information about medication dosage, frequency, timing, administration method, criticality, alternative medications or forms, and education.26,36 Patients and/or caregivers also indicated interest in communicating with inpatient providers by using the portal.16,27,28,30-37 In 1 study, patients highlighted the need to be involved in care plan development,27 which led to portal refinement to allow for patient-generated data entry, including care goals and a way to communicate real-time concerns and feedback.28

Studies also considered healthcare team perspectives to inform portal design.25,26,28,30,35,37 Although information needs usually overlapped, patient and healthcare team priorities differed in some areas. Although patients wanted to “know what was going to happen to them,” nurses in 1 study were more concerned about providing information to protect patients, such as safety and precaution materials.25 Similarly, when designing a medication-tracking tool, patients sought information that helped them understand what to expect, while pharmacists focused on medication safety and providing information that fit their workflow (eg, abstract medication schedules).36

Identified study data raised important portal interface design considerations. Results suggested clinical data should be presented by using simple displays,28 accommodating real-time information. Participants recommended links16,29 to personalized patient-friendly37 education accessed with minimal steps.26 Interfaces may be personalized for target users, such as patient or proxy and younger or older individuals. For example, older patients reported less familiarity with touch screens, internal keyboards, and handwriting recognition, favoring voice recognition for recording notes.27 This raised questions about how portals can be designed to best maintain patient privacy.25 Interface design, such as navigation, also relied heavily on hardware choice, such as tablet versus mobile phone.28

Inpatient Portal Use and Usability

Most patient and/or caregiver participants in included studies were interested in using an inpatient portal, used it when offered, found it easy to use, useful, and/or were satisfied with it.16,18,24-37 Most used and liked functionalities that provided healthcare team, test result, and medication information.22,33,37 In the 1 identified controlled trial,18 researchers evaluated an inpatient portal given to adult inpatients that included a problem list, schedule, medication list, and healthcare team information. Of the intervention unit patients, 80% used the portal, 76% indicated it was easy to use, and 71% thought it provided useful information. When a portal was given to 239 adult patients and caregivers in another study, 66% sent a total of 291 messages to the healthcare team.31 Of these, 153 provided feedback, 76 expressed preferences, and 16 communicated concerns. In a pediatric study, an inpatient portal was given to 296 parents who sent a total of 36 messages and 176 requests.33 Messages sent included information regarding caregiver needs, questions, updates, and/or positive endorsements of the healthcare team and/or care.