Hospitalist and Internal Medicine Leaders’ Perspectives of Early Discharge Challenges at Academic Medical Centers

Improving early discharges may improve patient flow and increase hospital capacity. We conducted a national survey of academic medical centers addressing the prevalence, importance, and effectiveness of early-discharge initiatives. We assembled a list of hospitalist and general internal medicine leaders at 115 US-based academic medical centers. We emailed each institutional representative a 30-item online survey regarding early-discharge initiatives. The survey included questions on discharge prioritization, the prevalence and effectiveness of early-discharge initiatives, and barriers to implementation. We received 61 responses from 115 institutions (53% response rate). Forty-seven (77%) “strongly agreed” or “agreed” that early discharge was a priority. “Discharge by noon” was the most cited goal (n = 23; 38%) followed by “no set time but overall goal for improvement” (n = 13; 21%). The majority of respondents reported early discharge as more important than obtaining translators for non-English-speaking patients and equally important as reducing 30-day readmissions and improving patient satisfaction. The most commonly reported factors delaying discharge were availability of postacute care beds (n = 48; 79%) and patient-related transport complications (n = 44; 72%). The most effective early discharge initiatives reported involved changes to the rounding process, such as preemptive identification and early preparation of discharge paperwork (n = 34; 56%) and communication with patients about anticipated discharge (n = 29; 48%). There is a strong interest in increasing early discharges in an effort to improve hospital throughput and patient flow.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Early Discharge as a Priority

Forty-seven (77%) institutional representatives strongly agreed or agreed that early discharge was a priority, with discharge by noon being the most common target time (n = 23; 38%). Thirty (50%) respondents rated early discharge as more important than improving interpreter use for non-English-speaking patients and equally important as reducing 30-day readmissions (n = 29; 48%) and improving patient satisfaction (n = 27; 44%).

Factors Delaying Discharge

The most common factors perceived as delaying discharge were considered external to the hospital, such as postacute care bed availability or scheduled (eg, ambulance) transport delays (n = 48; 79%), followed by patient factors such as patient transport issues (n = 44; 72%). Less commonly reported were workflow issues, such as competing primary team priorities or case manager bandwidth (n = 38; 62%; Table 1).

Initiatives to Improve Discharge

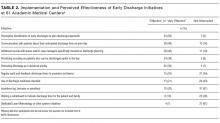

The most commonly implemented initiatives perceived as effective at improving discharge times were the preemptive identification of early discharges to plan discharge paperwork (n = 34; 56%), communication with patients about anticipated discharge time on the day prior to discharge (n = 29; 48%), and the implementation of additional rounds between physician teams and case managers specifically around discharge planning (n = 28; 46%). Initiatives not commonly implemented included regular audit of and feedback on discharge times to providers and teams (n = 21; 34%), the use of a discharge readiness checklist (n = 26; 43%), incentives such as bonuses or penalties (n = 37; 61%), the use of a whiteboard to indicate discharge times (n = 23; 38%), and dedicated quality-improvement approaches such as LEAN (n = 37; 61%; Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Our study suggests early discharge for medicine patients is a priority among academic institutions. Hospitalist and general internal medicine physician leaders in our study generally attributed delayed discharges to external factors, particularly unavailability of postacute care facilities and transportation delays. Having issues with finding postacute care placements is consistent with previous findings by Selker et al.15 and Carey et al.8 This is despite the 20-year difference between Selker et al.’s study and the current study, reflecting a continued opportunity for improvement, including stronger partnerships with local and regional postacute care facilities to expedite care transition and stronger discharge-planning efforts early in the admission process. Efforts in postacute care placement may be particularly important for Medicaid-insured and uninsured patients.

Our responders, hospitalist and internal medicine physician leaders, did not perceive the additional responsibilities of teaching and supervising trainees to be factors that significantly delayed patient discharge. This is in contrast to previous studies, which attributed delays in discharge to prolonged clinical decision-making related to teaching and supervision.4-6,8 This discrepancy may be due to the fact that we only surveyed single physician leaders at each institution and not residents. Our finding warrants further investigation to understand the degree to which resident skills may impact discharge planning and processes.

Institutions represented in our study have attempted a variety of initiatives promoting earlier discharge, with varying levels of perceived success. Initiatives perceived to be the most effective by hospital leaders centered on 2 main areas: (1) changing individual provider practice and (2) anticipatory discharge preparation. Interestingly, this is in discordance with the main factors labeled as causing delays in discharges, such as obtaining postacute care beds, busy case managers, and competing demands on primary teams. We hypothesize this may be because such changes require organization- or system-level changes and are perceived as more arduous than changes at the individual level. In addition, changes to individual provider behavior may be more cost- and time-effective than more systemic initiatives.

Our findings are consistent with the work published by Wertheimer and colleagues,11 who show that additional afternoon interdisciplinary rounds can help identify patients who may be discharged before noon the next day. In their study, identifying such patients in advance improved the overall early-discharge rate the following day.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Our survey only considers the perspectives of hospitalist and general internal medicine physician leaders at academic medical centers that are part of the Vizient Inc. collaborative. They do not represent all academic or community-based medical centers. Although the perceived effectiveness of some initiatives was high, we did not collect empirical data to support these claims or to determine which initiative had the greatest relative impact on discharge timeliness. Lastly, we did not obtain resident, nursing, or case manager perspectives on discharge practices. Given their roles as frontline providers, we may have missed these alternative perspectives.

Our study shows there is a strong interest in increasing early discharges in an effort to improve hospital throughput and patient flow.