Characterizing Hospitalist Practice and Perceptions of Critical Care Delivery

BACKGROUND: Intensivist shortages have led to increasing hospitalist involvement in critical care delivery.

OBJECTIVE: To characterize the practice of hospitalists practicing in the intensive care unit (ICU) setting.

DESIGN: Survey of hospital medicine physicians.

SETTING: This survey was conducted as a needs assessment for the ongoing efforts of the Critical Care Task Force of the Society of Hospital Medicine Education Committee. PARTICIPANTS: Hospitalists in the United States.

INTERVENTION: An iteratively developed, 25-item, web-based survey.

MEASUREMENTS: Results were compiled from all respondents then analyzed in subgroups. Various items were examined for correlations.

RESULTS: A total of 425 hospitalists completed the survey. Three hundred and twenty-five (77%) provided critical care services, and 280 (66%) served as primary physicians in the ICU. Hospitalists were significantly more likely to serve as primary physicians in rural ICUs (85% of rural respondents vs 62% of nonrural; P < .001 for association). Half of the rural hospitalists who were primary physicians for ICU patients felt obliged to practice beyond their scope, and 90% at least occasionally perceived that they had insufficient support from board-certified intensivists. Among respondents serving as primary physicians for ICU patients, 67% reported at least moderate difficulty transferring patients to higher levels of ICU care. Difficulty transferring patients was the only item significantly correlated with the perception of being expected to practice beyond one’s scope (P < .05 for association). CONCLUSIONS: Hospitalists frequently deliver critical care services without adequate training or support, most prevalently in rural hospitals. Without major changes in intensivist staffing or patient distribution, this is unlikely to change.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

RESULTS

Objective 1: Demographics and Practice Role

Four hundred and twenty-five hospitalists responded to the survey. The first 2 phases (pilot survey and distribution via professional networks) generated 101 responses, and the third phase (via SHM’s listserv) generated an additional 324 responses. As the survey was anonymous, we could not determine which hospitals or geographic regions were represented. Three hundred and twenty-five of the 425 hospitalists who completed the survey (77%) reported that they delivered care in the ICU. Of these 325 hospitalists, 45 served only as consultants, while the remaining 280 (66% of the total sample) served as the primary attending physician in the ICU. Among these primary providers of care in the ICU, 60 (21%) practiced in rural settings and 220 (79%) practiced in nonrural settings (Figure 1).

The demographics of our respondents were similar to those of the SHM annual survey,13 in which 66% of respondents delivered ICU care. Forty-one percent of our respondents worked in critical access or small community hospitals, 24% in academic medical centers, and 34% in large community centers with an academic affiliation. The SHM annual survey cohort included more physicians from nonteaching hospitals (58.7%) and fewer from academic medical centers (14.8%).13

Hospitalists’ presence in the ICU varied by practice setting (Table 1).

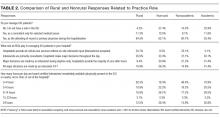

Hospitalists were significantly more prevalent in rural ICUs than in nonrural settings (96% vs 73%; Table 2).

We found similar results when comparing academic hospitalists (those working in an academic medical center or academic-affiliated hospital) with nonacademic hospitalists (those working in critical access or small community centers). Specifically, hospitalists in nonacademic settings were significantly more prevalent in ICUs (90% vs 67%; Table 2), more likely to serve as the primary attending (81% vs 55%), and more likely to deliver all critical care services (64% vs 25%). Sixty-four percent of respondents from nonacademic settings reported that hospitalists manage all or most ICU patients in their hospital as opposed to 25% for academic respondents (χ2P value for association <.001). Intensivist availability was also significantly lower in nonacademic ICUs (Table 2).

We also sought to determine whether the ability to transfer critically ill patients to higher levels of care effectively mitigated shortfalls in intensivist staffing. When restricted to hospitalists who served as primary providers for ICU patients, 28% of all respondents and 51% of rural hospitalists reported transferring patients to a higher level of care.

Sixty-seven percent of hospitalists who served as primary physicians for ICU patients in any setting reported at least moderate difficulty arranging transfers to higher levels of care.

Objective 2: Identifying the Practice Gap

Hospitalists’ perceptions of practicing critical care beyond their skill level and without sufficient board-certified intensivist support varied by both practice location and practice type (Table 3).

There were similar discrepancies between academic and nonacademic respondents. Forty-two percent of respondents practicing in nonacademic settings reported being expected to practice beyond their scope at least some of the time, and 18% reported that intensivist support was never sufficient. This contrasts with academic hospitalists, of whom 35% reported feeling expected to practice outside their scope, and less than 4% reported the available support from intensivists was never sufficient. For comparisons of academic and nonacademic respondents, only perceptions of sufficient board-certified intensivist support reached statistical significance (Table 3).

The role of intensivists in making management decisions and the strategy for ventilator management decisions correlated significantly with perception of intensivist support (P < .001) but not with the perception of practicing beyond one’s scope. The number of ventilated patients did not correlate significantly with either perception of intensivist support or of being expected to practice beyond scope.

Difficulty transferring patients to a higher level of care was the only attribute that significantly correlated with hospitalists’ perceptions of having to practice beyond their skill level (P < .05; Table 3). Difficulty of transfer was also significantly associated with perceived adequacy of board-certified intensivist support (P < .001). Total hours of intensivist coverage, intensivist role in decision making, and ventilator management arrangements also correlated significantly with the perceived adequacy of board-certified intensivist support (P < .001 for all; Table 3).