The Evaluation of Medical Inpatients Who Are Admitted on Long-term Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain

Individuals who are on long-term opioid therapy (LTOT) for chronic noncancer pain are frequently admitted to the hospital with acute pain, exacerbations of chronic pain, or comorbidities. Consequently, hospitalists find themselves faced with complex treatment decisions in the context of uncertainty about the effectiveness of LTOT as well as concerns about risks of overdose, opioid use disorders, and adverse events. Our multidisciplinary team sought to synthesize guideline recommendations and primary literature relevant to assessing medical inpatients on LTOT, with the objective of assisting practitioners in balancing effective pain treatment and opioid risk reduction. We identified no primary studies or guidelines specific to assessing medical inpatients on LTOT. Recommendations from outpatient guidelines on LTOT and guidelines on pain management in acute-care settings include the following: evaluate both pain and functional status, differentiate acute from chronic pain, investigate the preadmission course of opioid therapy, obtain a psychosocial history, screen for mental health conditions, screen for substance use disorders, check state prescription drug monitoring databases, order urine drug immunoassays, detect use of sedative-hypnotics, and identify medical conditions associated with increased risk of overdose and adverse events. Although approaches to assessing medical inpatients on LTOT can be extrapolated from related guidelines, observational studies, and small studies in surgical populations, more work is needed to address these critical topics for inpatients on LTOT.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Obtaining a Comprehensive Pain History

Hospitalists newly evaluating patients on LTOT often face a dual challenge: deciding if the patient has an immediate indication for additional opioids and if the current long-term opioid regimen should be altered or discontinued. In general, opioids are an accepted short-term treatment for moderate to severe acute pain but their role in chronic noncancer pain is controversial. Newly released guidelines by the CDC recommend initiating LTOT as a last resort, and the Departments of Veterans Affairs and Defense guidelines recommend against initiation of LTOT.22,23

A key first step, therefore, is distinguishing between acute and chronic pain. Among patients on LTOT, pain can represent a new acute pain condition, an exacerbation of chronic pain, opioid-induced hyperalgesia, or opioid withdrawal. Acute pain is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in relation to such damage.26 In contrast, chronic pain is a complex response that may not be related to actual or ongoing tissue damage, and is influenced by physiological, contextual, and psychological factors. Two acute pain guidelines and 1 chronic pain guideline recommend distinguishing acute and chronic pain,9,16,21 3 chronic pain guidelines reinforce the importance of obtaining a pain history (including timing, intensity, frequency, onset, etc),20,22,23 and 6 guidelines recommend ascertaining a history of prior pain-related treatments.9,13,14,16,20,22 Inquiring how the current pain compares with symptoms “on a good day,” what activities the patient can usually perform, and what the patient does outside the hospital to cope with pain can serve as entry into this conversation.

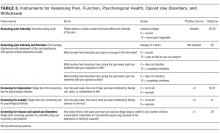

In addition to function, 5 guidelines, including 2 specific guidelines for acute pain or the hospital setting, recommend obtaining a detailed psychosocial history to identify life stressors and gain insight into the patient’s coping skills.14,16,19,20,22 Psychiatric symptoms can intensify the experience of pain or hamper coping ability. Anxiety, depression, and insomnia frequently coexist in patients with chronic pain.31 As such, 3 hospital setting/acute pain guidelines and 3 chronic pain guidelines recommend screening for mental health issues including anxiety and depression.13,14,16,20,22,23 Several depression screening instruments have been validated among inpatients,32 and there are validated single-item, self-administered instruments for both depression and anxiety (Table 3).32,33

Although obtaining a comprehensive history before making treatment decisions is ideal, some patients present in extremis. In emergency departments, some guidelines endorse prompt administration of analgesics based on patient self-report, prior to establishing a diagnosis.17 Given concerns about the growing prevalence of opioid use disorders, several states now recommend emergency medicine prescribers screen for misuse before giving opioids and avoid parenteral opioids for acute exacerbations of chronic pain.34 Treatments received in emergency departments set patients’ expectations for the care they receive during hospitalization, and hospitalists may find it necessary to explain therapies appropriate for urgent management are not intended to be sustained.

Identifying Misuse and Opioid Use Disorders

Nonmedical use of prescription opioids and opioid use disorders have more than doubled over the last decade.35 Five guidelines, including 3 specific guidelines for acute pain or the hospital setting, recommend screening for opioid misuse.13,14,16,19,23 Many states mandate practitioners assess patients for substance use disorders before prescribing controlled substances.36 Instruments to identify aberrant and risky use include the Current Opioid Misuse Measure,37 Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire,38 Addiction Behaviors Checklist,39 Screening Tool for Abuse,40 and the Self-Administered Single-Item Screening Question (Table 3).41 However, the evidence for these and other tools is limited and absent for the inpatient setting.21,42

In addition to obtaining a history from the patient, 4 guidelines specific to hospital settings/acute pain and 4 chronic pain guidelines recommend practitioners access prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs).13-16,19,21-24 PDMPs exist in all states except Missouri, and about half of states mandate practitioners check the PDMP database in certain circumstances.36 Studies examining the effects of PDMPs on prescribing are limited, but checking these databases can uncover concerning patterns including overlapping prescriptions or multiple prescribers.43 PDMPs can also confirm reported medication doses, for which patient report may be less reliable.

Two hospital/acute pain guidelines and 5 chronic pain guidelines also recommend urine drug testing, although differing on when and whom to test, with some favoring universal screening.11,20,23 Screening hospitalized patients may reveal substances not reported by patients, but medications administered in emergency departments can confound results. Furthermore, the commonly used immunoassay does not distinguish heroin from prescription opioids, nor detect hydrocodone, oxycodone, methadone, buprenorphine, or certain benzodiazepines. Chromatography/mass spectrometry assays can but are often not available from hospital laboratories. The differential for unexpected results includes substance use, self treatment of uncontrolled pain, diversion, or laboratory error.20

If concerning opioid use is identified, 3 hospital setting/acute pain specific guidelines and the CDC guideline recommend sharing concerns with patients and assessing for a substance use disorder.9,13,16,22 Determining whether patients have an opioid use disorder that meets the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th Edition44 can be challenging. Patients may minimize or deny symptoms or fear that the stigma of an opioid use disorder will lead to dismissive or subpar care. Additionally, substance use disorders are subject to federal confidentiality regulations, which can hamper acquisition of information from providers.45 Thus, hospitalists may find specialty consultation helpful to confirm the diagnosis.