How Exemplary Teaching Physicians Interact with Hospitalized Patients

BACKGROUND: Effectively interacting with patients defines the consummate clinician.

OBJECTIVE: As part of a broader study, we examined how 12 carefully selected attending physicians interacted with patients during inpatient teaching rounds.

DESIGN: A multisite study using an exploratory, qualitative approach.

PARTICIPANTS: Exemplary teaching physicians were identified using modified snowball sampling. Of 59 potential participants, 16 were contacted, and 12 agreed to participate. Current and former learners of the participants were also interviewed. Participants were from hospitals located throughout the United States.

INTERVENTION: Two researchers—a physician and a medical anthropologist—conducted 1-day site visits, during which they observed teaching rounds and patient-physician interactions and interviewed learners and attendings.

MEASUREMENTS: Field notes were taken during teaching rounds. Interviews were recorded and transcribed, and code reports were generated.

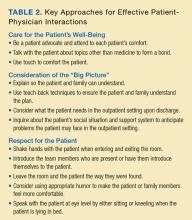

RESULTS: The attendings generally exhibited the following 3 thematic behaviors when interacting with patients: (1) care for the patient’s well-being by being a patient advocate and forming a bond with the patient; (2) consideration of the “big picture” of the patient’s medical and social situation by anticipating what the patient may need upon discharge and inquiring about the patient’s social situation; and (3) respect for the patient through behaviors such as shaking hands with the patient and speaking with the patient at eye level by sitting or kneeling.

CONCLUSIONS: The key findings of our study (care for the patient’s well-being, consideration of the “big picture,” and respect for the patient) can be adopted and honed by physicians to improve their own interactions with hospitalized patients.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Interviews and Focus Groups

The research team also conducted individual, semistructured interviews with the attendings (n = 12), focus groups with their current teams (n = 46), and interviews or focus groups with their former learners (n = 26). Current learners were asked open-ended questions about their roles on the teams, their opinions of the attendings, and the care the attendings provide to their patients. Because they were observed during rounds, the researchers asked for clarification about specific interactions observed during the teaching rounds. Depending on availability and location, former learners either participated in in-person focus groups or interviews on the day of the site visit, or in a later telephone interview. All interviews and focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed.

This study was deemed to be exempt from regulation by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. All participants were informed that their participation was completely voluntary and that they could refuse to answer any question.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using a thematic analysis approach,20 which involves reading through the data to identify patterns (and create codes) that relate to behaviors, experiences, meanings, and activities. The patterns are then grouped into themes to help further explain the findings.21 The research team members (S.S. and M.H.) met after the first site visit and developed initial ideas about meanings and possible patterns. One team member (M.H.) read all the transcripts from the site visit and, based on the data, developed a codebook to be used for this study. This process was repeated after every site visit, and the coding definitions were refined as necessary. All transcripts were reviewed to apply any new codes when they developed. NVivo® 10 software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) was used to assist with the qualitative data analysis.

To ensure consistency and identify relationships between codes, code reports listing all the data linked to a specific code were generated after all the field notes and transcripts were coded. Once verified, codes were grouped based on similarities and relationships into prominent themes related to physician-patient interactions by 2 team members (S.S. and M.H.), though all members reviewed them and concurred.

RESULTS

C are for the Patient’s Well-Being

The attendings we observed appeared to openly care for their patients’ well-being and were focused on the patients’ wants and needs. We noted that attendings were generally very attentive to the patients’ comfort. For example, we observed one attending sending the senior resident to find the patient’s nurse in order to obtain additional pain medications. The attending said to the patient several times, “I’m sorry you’re in so much pain.” When the team was leaving, she asked the intern to stay with the patient until the medications had been administered.

The attendings we observed could also be considered patient advocates, ensuring that patients received superb care. As one learner said about an attending who was attempting to have his patient listed for a liver transplant, “He is the biggest advocate for the patient that I have ever seen.” Regarding the balance between learning biomedical concepts and advocacy, another learner noted the following: “… there is always a teaching aspect, but he always makes sure that everything is taken care of for the patient…”

Building rapport creates and sustains bonds between people. Even though most of the attendings we observed primarily cared for hospitalized patients and had little long-term continuity with them, the attendings tended to take special care to talk with their patients about topics other than medicine to form a bond. This bonding between attending and patient was appreciated by learners. “Probably the most important thing I learned about patient care would be taking the time and really developing that relationship with patients,” said one of the former learners we interviewed. “There’s a question that he asks to a lot of our patients,” one learner told us, “especially our elderly patients, that [is], ‘What’s the most memorable moment in your life?’ So, he asks that question, and patient[s] open up and will share.”

The attendings often used touch to further solidify their relationships with their patients. We observed one attending who would touch her patients’ arms or knees when she was talking with them. Another attending would always shake the patient’s hand when leaving. Another attending would often lay his hand on the patient’s shoulder and help the patient sit up during the physical examination. Such humanistic behavior was noticed by learners. “She does a lot of comforting touch, particularly at the end of an exam,” said a current learner.