Hospitalist Perspective of Interactions with Medicine Subspecialty Consult Services

BACKGROUND: Medicine subspecialty consultation is becoming increasingly important in inpatient medicine.

OBJECTIVE: We conducted a survey study in which we examined hospitalist practices and attitudes regarding medicine subspecialty consultation.

DESIGN AND SETTING: The survey instrument was developed by the authors based on prior literature and administered online anonymously to hospitalists at 4 academic medical centers in the United States.

MEASUREMENTS: The survey evaluated 4 domains: (1) current consultation practices, (2) preferences regarding consultation, (3) barriers to and facilitating factors of effective consultation, and (4) a comparison between hospitalist–fellow and hospitalist–subspecialty attending interactions.

RESULTS: One hundred twenty-two of 261 hospitalists (46.7%) responded. The majority of hospitalists interacted with fellows during consultation. Of those, 90.9% reported that in-person communication occurred during less than half of consultations, and 64.4% perceived pushback at least “sometimes” in their consult interactions. Participants viewed consultation as an important learning experience, preferred direct communication with the consulting service, and were interested in more teaching during consultation. The survey identified a number of barriers to and facilitating factors of an effective hospitalist–consultant interaction, which impacted both hospitalist learning and patient care. Hospitalists reported more positive experiences when interacting with subspecialty attendings compared to fellows with regard to multiple aspects of the consultation.

CONCLUSION: The hospitalist–consultant interaction is viewed as important for both hospitalist learning and patient care. Multiple barriers and facilitating factors impact the interaction, many of which are amenable to intervention.

©2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Statistics

Results were summarized using the mean with standard deviation for continuous variables and the frequency with percentage for categorical variables after excluding missing values. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A 2-sided P value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Current Consultation Practices

Current consultation practices and descriptions of hospitalist–consultant communication are shown in Table 2. Forty percent of respondents requested 0-1 consults per day, while 51.7% requested 2-3 per day. The most common reasons for requesting a consultation were assistance with treatment (48.5%), assistance with diagnosis (25.7%), and request for a procedure (21.8%). When asked whether the frequency of consultation is changing, slightly more hospitalists felt that their personal use of consultation was increasing as compared to those who felt that it was decreasing (38.5% vs 30.3%, respectively).

Hospitalist Preferences

Eighty-six percent of respondents agreed that consultants should be required to communicate their recommendations either in person or over the phone. Eighty-three percent of hospitalists agreed that they would like to receive more teaching from the consulting services, and 74.0% agreed that consultants should attempt to teach hospitalists during consult interactions regardless of whether the hospitalist initiates the teaching–learning interaction.

Barriers to and Facilitating Factors of Effective Consultation

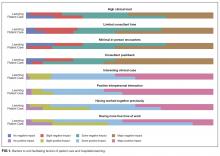

Participants reported that multiple factors affected patient care and their own learning during inpatient consultation (Figure 1). Consultant pushback, high hospitalist clinical workload, a perception that consultants had limited time, and minimal in-person interactions were all seen as factors that negatively affected the consult interaction. These generally affected both learning and patient care. Conversely, working on an interesting clinical case, more hospitalist free time, positive interaction with the consultant, and having previously worked with the consultant positively affected both learning and patient care (Figure 1).

Fellow Versus Attending Interactions

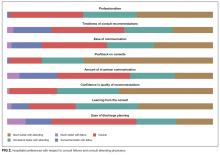

Respondents indicated that interacting directly with the consult attending was superior to hospitalist–fellow interactions in all aspects of care but particularly with respect to pushback, confidence in recommendations, professionalism, and hospitalist learning (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe hospitalist attending practices, attitudes, and perceptions of internal medicine subspecialty consultation. Our findings, which focus on the interaction between hospitalists and internal medicine subspecialty attendings and fellows, outline the hospitalist perspective on consultant interactions and identify a number of factors that are amenable to intervention. We found that hospitalists perceive the consult interaction to be important for patient care and a valuable opportunity for their own learning. In-person communication was seen as an important component of effective consultation but was reported to occur in a minority of consultations. We demonstrate that hospitalist–subspecialty attending consult interactions are perceived more positively than hospitalist–fellow interactions. Finally, we describe barriers and facilitating factors that may inform future interventions targeting this important interaction.