Penalizing Physicians for Low-Value Care in Hospital Medicine: A Randomized Survey

Low-value services—those for which there is little to no benefit, little benefit relative to cost, or outsized potential harm compared with benefit—persist widely despite professional consensus, guidelines, and national campaigns to reduce them. As policy makers consider financially penalizing physicians to deter low-value services, physician support for such penalties remains unknown. We conducted a randomized survey experiment among physicians to evaluate how the framing of harms from low-value care—in terms of those to patients, healthcare institutions, or society—influenced physician support of financial penalties for low-value care services. Policy support rate was 39.6% overall and highest when the harms of low-value care were framed as costs to society (48.4%). Compared with respondents receiving the “patient harm” version, those receiving the “societal harm” version (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 2.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.20-6.69), but not the “institutional harm” framing (adjusted OR 1.53; 95% CI, 0.66-3.53), were more likely to report policy support. Our results suggest that emphasizing the impact of these harms may increase acceptability of financial penalties among physicians and contribute to the larger effort to decrease low-value care in hospital settings.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

RESULTS

Of 484 eligible respondents, 187 (39%) completed the survey. Compared with nonrespondents, respondents were more likely to be female (30% vs 26%, P = 0.001), older (mean age 41 vs 36 years, P < 0.001), and practicing clinicians rather than internal medicine residents (87% vs 69%, P < 0.001). Physician characteristics were similar across the 3 survey versions (Table). Most respondents agreed that financial incentives for individual physicians is an effective way to improve the value of healthcare (73.3%) and that physicians should consider the costs of a test or treatment to society when making clinical decisions for patients (79.1%). The majority also felt that clinicians have a duty to offer a test or treatment to a patient if it has any chance of helping them (70.1%) and that it is inappropriate for anyone beyond the clinician and patient to decide if a test or treatment is “worth the cost” (63.6%).

Overall, policy support rate was 39.6% and was the highest for the “societal harm” version (48.4%), followed by the “institutional harm” (36.9%) and “patient harm” (33.3%) versions. Compared with respondents receiving the “patient harm” version, those receiving the “societal harm” version (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 2.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.20-6.69), but not the “institutional harm” framing (adjusted OR 1.53; 95% CI, 0.66-3.53), were more likely to report policy support. Policy support was also higher among those who agreed that providing financial incentives to individual physicians is an effective way to improve the value of healthcare (adjusted OR 4.61; 95% CI, 1.80-11.80).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to prospectively evaluate physician support of financial penalties for low-value services relevant to hospital medicine. It has 2 main findings.

First, although overall policy support was relatively low (39.6%), it varied significantly on the basis of how the harms of low-value care were framed. Support was highest in the “societal harm” version, suggesting that emphasizing these harms may increase acceptability of financial penalties among physicians and contribute to the larger effort to decrease low-value care in hospital settings. The comparatively low support for the “patient harm” version is somewhat surprising but may reflect variation in the nature of harm, benefit, and cost trade-offs for individual low-value services, as noted above, and physician belief that some low-value services do not in fact produce significant clinical harms.

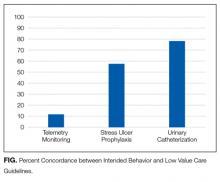

For example, whereas evidence demonstrates that stress ulcer prophylaxis in non-ICU patients can harm patients through nosocomial infections and adverse drug effects,10,11 the clinical harms of telemetry are less obvious. Telemetry’s low value derives more from its high cost relative to benefit, rather than its potential for clinical harm.6 The many paths to “low value” underscore the need to examine attitudes and uptake toward these services separately and may explain the wide range in concordance between intended clinical behavior and low-value care guidelines (11.8% to 78.6%).

Reinforcing policies could more effectively deter low-value care. For example, multiple forces, including Medicare payment reform and national accreditation policies,12,13 have converged to discourage low-value use of urinary catheters in hospitalized patients. In contrast, there has been little reinforcement beyond consensus guidelines to reduce low-value use of telemetric monitoring. Given questions about whether consensus methods alone can deter low-value care beyond obvious “low hanging fruit,”14 policy makers could coordinate policies to accelerate progress within other priority areas.

Broad policies should also be paired with local initiatives to influence physician behavior. For example, health systems have begun successfully leveraging the electronic medical record and utilizing behavioral economics principles to design interventions to reduce inappropriate overuse of antibiotics for upper respiratory infections in primary care clinics.15 Organizations are also redesigning care processes in response to resource utilization imperatives under ongoing value-based care payment reform. Care redesign and behavioral interventions embedded at the point of care can both help deter low-value services in inpatient settings.

Study limitations include a relatively low response rate, which limits generalizability. However, all 3 randomized groups were similar on measured characteristics, and experimental randomization reduces the nonresponse bias concerns accompanying descriptive surveys. Additionally, although we evaluated intended clinical behavior in a national sample, our results may not reflect actual behavior among all physicians practicing hospital medicine. Future work could include assessments of actual or self-reported practices or examine additional factors, including site, years of practice, knowledge about guidelines, and other possible determinants of guideline-concordant behaviors.

Despite these limitations, our study provides important early evidence about physician support of financial penalties for low-value care relevant to hospital medicine. As policy makers design and organizational leaders implement financial incentive policies, this information can help increase their acceptability among physicians and more effectively reduce low-value care within hospitals.