Supporting Faculty Development in Hospital Medicine: Design and Implementation of a Personalized Structured Mentoring Program

The guidance of a mentor can have a tremendous influence on the careers of academic physicians. The lack of mentorship in the relatively young field of hospital medicine has been documented, but the efficacy of formalized mentorship programs has not been well studied. We implemented and evaluated a structured mentorship program for junior faculty at a large academic medical center. Of the 16 mentees who participated in the mentorship program, 14 (88%) completed preintervention surveys and 10 (63%) completed postintervention surveys. After completing the program, there was a statistically significant improvement in overall satisfaction within 5 specific domains: career planning, professional connectedness, self-reflection, research skills, and mentoring skills. All mentees reported that they would recommend that all hospital medicine faculty participate in similar mentorship programs. In this small, single-center pilot study, we found that the addition of a structured mentorship program based on training sessions that focus on best practices in mentoring was feasible and led to increased satisfaction in certain career domains among early-career hospitalists. Larger prospective studies with a longer follow-up are needed to assess the generalizability and durability of our findings.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Program Evaluation

Statistical Analysis

RESULTS

Program Participation and Response Rate

Of the 25 eligible mentees, 16 (64%) participated in the mentorship program. Of the 20 eligible mentors, 12 (60%) participated. One participating mentee and 1 mentor left the institution during the intervention period. Fourteen mentees (response rate: 88%) and 9 mentors (response rate: 75%) completed the preintervention survey. Ten mentees (response rate: 63%) and 8 mentors (response rate: 67%) completed the postintervention survey.

Mentor Characteristics

Mentorship Meetings and the Mentorship Network

All participants attended at least 2 of the 3 trainings. For the mentees who completed the postintervention survey, 9 (90%) met with their mentors 3 or more additional times, and 8 (80%) were connected by their mentor to at least 1 additional faculty mentor.

Perceptions and Overall Satisfaction with Mentorship

Prior to starting the mentoring relationship, 86% of mentees and 78% of mentors anticipated that differing career goals would be a challenge to a successful mentor–mentee relationship. At the end of the program, only 30% of mentees and 38% of mentors felt that such differences were a challenge. Ninety percent of mentees and 88% of mentors were satisfied or very satisfied with their mentorship match. Forty-three percent of mentees felt supported by the HMU prior to the mentorship program, while 90% felt supported after the program. All the mentees agreed that future HMU faculty should participate in a similar program.

Impact of Mentorship on Critical Domains

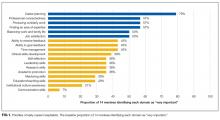

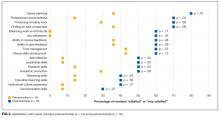

At baseline, the following domains were most commonly rated as very important by mentees: career planning, professional connectedness, producing scholarly work, finding an area of expertise, balancing work and family life, and job satisfaction (Figure 1). There was a significant improvement in composite satisfaction scores after completion of the mentorship program (54.5 ± 6.2 vs 65 ± 14.9, P = 0.02). The influence of the mentorship program on all domains is shown in Figure 2.

DISCUSSION

Our pilot structured mentorship program for junior hospitalists was feasible and led to improved satisfaction in select key career domains. Other mentoring or faculty coaching programs have been studied in several fields of medicine10-12; however, to our knowledge, there have not been published data studying a structured mentorship program for junior faculty in hospital medicine. Our intervention prioritized not only optimizing mentorship matches but also formalizing training sessions led by content experts.

After experiencing a structured mentoring relationship, most mentees felt a greater sense of support, were satisfied with their mentoring experiences, were connected to additional faculty, and had significant improvement in satisfaction in key career domains. Satisfaction with other self-identified “very important” domains, including scholarly activity, finding an area of expertise, job satisfaction, and work and family-life balance, did not significantly improve by the end of the program.

Perceived challenges to mentoring did not persist to the same degree with the implementation of a structured program. This highlights the importance of building mentorship skill sets (such as mentoring across differences and goal setting) through expert-led training sessions and perhaps also the importance of matching based on career goals.