Dust in the Wind

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient’s case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant.

Moderate distress, increased work of breathing, tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypoxia are all worrisome signs. Her temperature is subnormal, although this may not be accurate, as oral temperatures may register lower in patients with increased respiratory rates because of increased air flow across the thermometer. Bibasilar crackles with decreased bibasilar sounds require further investigation. A complete blood count, complete metabolic profile, troponin, arterial blood gas (ABG), electrocardiogram (ECG), and chest radiograph are warranted.

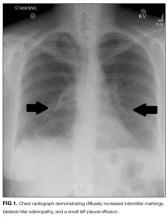

Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 8600 per mm3 with 11% bands and 7.3% eosinophils, and a hemoglobin count of 15 gm/dL. Basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, coagulation panel, and urinalysis were within normal limits, including serum creatinine 0.7 mg/dL, sodium 143 mmoL/L, chloride 104 mmoL/L, bicarbonate 30 mEq/L, anion gap 9 mmoL/L, and blood urea nitrogen 12 mg/dL. Chest radiograph disclosed diffusely increased interstitial markings and a small left pleural effusion (Figure 1).

Her bandemia suggests infection. Stress can cause a leukocytosis by demargination of mature white blood cells; however, stress does not often cause immature cells such as bands to appear. Her chest radiograph with diffuse interstitial markings is consistent with a community-acquired pneumonia. Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated because of the possibility of community-acquired pneumonia. Recent studies demonstrate that steroids decrease mortality, the need for mechanical ventilation, and the length of stay for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia; therefore, this patient should also be treated with steroids.

Eosinophilia may be seen in drug reactions, allergies, pulmonary emboli, pleural effusions, and occasionally in malignancy. Eosinophilic pneumonia typically has the “reverse pulmonary edema” picture, with infiltrates in the periphery and not centrally, as in congestive heart failure.

A serum bicarbonate of 30 mEq/L suggests a metabolic compensation for a chronic respiratory acidosis as renal compensation, and rise in bicarbonate generally takes 3 days. She may have been hypoxic longer than her symptoms suggest.

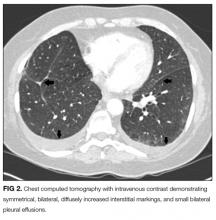

An ABG should be ordered to determine the degree of hypoxia and whether a higher level of care is indicated. The abnormal chest radiograph, along with her hypoxia, merits a closer look at her lung parenchyma with chest computed tomography (CT). A D-dimer would be beneficial to rule out pulmonary embolism. If the D-dimer is positive, chest CT with contrast is indicated to determine if a pulmonary embolism is present. A brain natriuretic peptide would assist in the diagnosis of congestive heart failure. A sputum culture and Gram stain and respiratory viral panel may establish a pathogen for pneumonia. An ECG and troponin to rule out myocardial infarction should be performed as well.

The presence of hilar and subcarinal lymph nodes expands the differential. Stage IV pulmonary sarcoid may present with diffuse infiltrates and nodes, although the acuity in this case makes it less likely. A very aggressive malignancy such as Burkitt lymphoma may have these findings. Acute viral and atypical pneumonias remain possible. Right middle lobe syndrome may cause partial collapse of the right middle lobe. Tuberculosis can be associated with right middle lobe syndrome; however, in this day and age an obstructing mass is more likely the cause. Pulmonary disease, such as cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and interstitial lung disease, should be considered in patients with pneumonia unresponsive to antibiotics. Lung biopsy and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) would help make the diagnosis and should be the next step, unless her degree of hypoxia is prohibitive. Similarly, thoracentesis with analysis of the pleural fluid for cell count, Gram stain, and culture may help make the diagnosis. Thoracentesis should be done with fluoroscopic guidance, given the risk of pneumothorax, which would further compromise her tenuous respiratory status.

Thoracentesis was attempted, but the pleural effusion was too small to provide a sample. Subsequent serum blood counts with differential showed an increased eosinophilia to 20% and resolved bandemia. Upon further questioning, she recalled several months of extensive, daily, fine-dust exposure from demolition during the remodeling of a new building.

Hypereosinophilia and pulmonary infiltrates narrow the differential considerably to include asthma; parasitic infection, such as the pulmonary phase of ascariasis; exposure, such as to dust, cigarettes, or asbestosis; or hypereosinophilic syndromes characterized by peripheral eosinophilia, along with a tissue eosinophilia, causing organ dysfunction. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome, a hypereosinophilic syndrome of unknown etiology despite extensive diagnostic testing, is rare, and eosinophilic leukemia even rarer. Her history strongly suggests exposure. Many eosinophilic diseases respond rapidly to steroids, and response to treatment would help narrow the diagnosis. If she does not respond to steroids, a lung and/or bone marrow biopsy would be the next step.

A BAL of the right middle lobe revealed 51% eosinophils, 3% neutrophils, 15% macrophages, and 28% lymphocytes. Gram stain, as well as cultures for bacteria, acid fast bacilli, fungus, herpes simplex virus, and cytomegalovirus cultures, were negative. Transbronchial lung biopsy revealed focal interstitial fibrosis and inflammation, without evidence of infection.

Eosinophils are primarily located in tissues; therefore, peripheral blood eosinophil counts often underestimate the degree of infiltration into end organs such as the lung. With 50% eosinophils, her BAL reflects this. Mold, fungus, chemical, and particle exposure could produce an eosinophilic BAL. She does not appear to be at risk for parasitic exposure. Eosinophilic granulomatosis (previously known as Churg-Strauss) is a consideration, but the lack of signs of vasculitis and wheezing make this less likely. A negative antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody may provide reassurance. “Fine dust exposure” is consistent with environmental exposure but not a specific antigen. Steroids provide a brisk eosinophil reduction and are appropriate for this patient. There is the possibility of missing infectious or parasitic etiologies; therefore, a culture of BAL fluid should be sent.