Associations of Physician Empathy with Patient Anxiety and Ratings of Communication in Hospital Admission Encounters

BACKGROUND: Responding empathically when patients express negative emotion is a recommended component of patient-centered communication.

OBJECTIVE: To assess the association between the frequency of empathic physician responses with patient anxiety, ratings of communication, and encounter length during hospital admission encounters.

DESIGN: Analysis of coded audio-recorded hospital admission encounters and pre- and postencounter patient survey data.

SETTING: Two academic hospitals.

PARTICIPANTS: Seventy-six patients admitted by 27 attending hospitalist physicians.

MEASUREMENTS: Recordings were transcribed and analyzed by trained coders, who counted the number of empathic, neutral, and nonempathic verbal responses by hospitalists to their patients’ expressions of negative emotion. We developed multivariable linear regression models to test the association between the number of these responses and the change in patients’ State Anxiety Scale (STAI-S) score pre- and postencounter and encounter length. We used Poisson regression models to examine the association between empathic response frequency and patient ratings of the encounter.

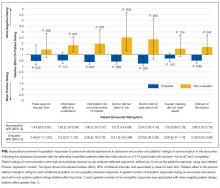

RESULTS: Each additional empathic response from a physician was associated with a 1.65-point decline in the STAI-S anxiety scale (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.48-2.82). Frequency of empathic responses was associated with improved patient ratings for covering points of interest, feeling listened to and cared about, and trusting the doctor. The number of empathic responses was not associated with encounter length (percent change in encounter length per response 1%; 95% CI, −8%-10%).

CONCLUSIONS: Responding empathically when patients express negative emotion was associated with less patient anxiety and higher ratings of communication but not longer encounter length.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

RESULTS

We analyzed data from admission encounters with 76 patients (consent rate 63%) and 27 hospitalists (consent rate 91%). Their characteristics are shown in Table 3. Median encounter length was 19 minutes (mean 21 minutes, range 3-68). Patients expressed negative emotion in 190 instances across all encounters; median number of expressions per encounter was 1 (range 0-14). Hospitalists responded empathically to 32% (n = 61) of the patient expressions, neutrally to 43% (n = 81), and nonempathically to 25% (n = 48).

The STAI-S was normally distributed. The mean preencounter STAI-S score was 39 (standard deviation [SD] 8.9). Mean postencounter STAI-S score was 38 (SD 10.7). Mean change in anxiety over the course of the encounter, calculated as the postencounter minus preencounter mean was −1.2 (SD 7.6). Table 1 shows summary statistics for the patient ratings of communication items. All items were rated highly. Across the items, between 51% and 78% of patients rated the highest score of 10.

Across the range of frequencies of emotional expressions per encounter in our data set (0-14 expressions), each additional empathic hospitalist response was associated with a 1.65-point decrease in the STAI-S (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.48-2.82). We did not find significant associations between changes in the STAI-S and the number of neutral hospitalist responses (−0.65 per response; 95% CI, −1.67-0.37) or nonempathic hospitalist responses (0.61 per response; 95% CI, −0.88-2.10).

In addition, nonempathic responses were associated with more negative ratings of communication for 5 of the 7 items: ease of understanding information, covering points of interest, the doctor listening, the doctor caring, and trusting the doctor. For example, for the item “I felt this doctor cared about me,” each nonempathic hospitalist response was associated with a more than doubling of negative patient ratings (aRE: 2.3; 95% CI, 1.32-4.16). Neutral physician responses to patient expressions of negative emotion were associated with less negative patient ratings for 2 of the items: covering points of interest (aRE 0.68; 95% CI, 0.51-0.90) and trusting the doctor (aRE: 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.99).

We did not find a statistical association between encounter length and the number of empathic hospitalist responses in the encounter (percent change in encounter length per response [PC]: 1%; 95% CI, −8%-10%) or the number of nonempathic responses (PC: 18%; 95% CI, −2%-42%). We did find a statistically significant association between the number of neutral responses and encounter length (PC: 13%; 95% CI, 3%-24%), corresponding to 2.5 minutes of additional encounter time per neutral response for the median encounter length of 19 minutes.

DISCUSSION

Our study set out to measure how hospitalists responded to expressions of negative emotion during admission encounters with patients and how those responses correlated with patient anxiety, ratings of communication, and encounter length. We found that empathic responses were associated with diminishing patient anxiety after the visit, as well as with better ratings of several domains of hospitalist communication. Moreover, nonempathic responses to negative emotion were associated with more strongly negative ratings of hospitalist communication. Finally, while clinicians may worry that encouraging patients to speak further about emotion will result in excessive visit lengths, we did not find a statistical association between empathic responses and encounter duration. To our knowledge, this is the first study to indicate an association between empathy and patient anxiety and communication ratings within the hospitalist model, which is rapidly becoming the predominant model for providing inpatient care in the United States.4,5

As in oncologic care, anxiety is an emotion commonly confronted by clinicians meeting admitted medical patients for the first time. Studies show that not only do patient anxiety levels remain high throughout a hospital course, patients who experience higher levels of anxiety tend to stay longer in the hospital.1,2,27-30 But unlike oncologic care or other therapy provided in an outpatient setting, the hospitalist model does not facilitate “continuity” of care, or the ability to care for the same patients over a long period of time. This reality of inpatient care makes rapid, effective rapport-building critical to establishing strong physician-patient relationships. In this setting, a simple communication tool that is potentially able to reduce inpatients’ anxiety could have a meaningful impact on hospitalist-provided care and patient outcomes.

In terms of the magnitude of the effect of empathic responses, the clinical significance of a 1.65-point decrease in the STAI-S anxiety score is not precisely clear. A prior study that examined the effect of music therapy on anxiety levels in patients with cancer found an average anxiety reduction of approximately 9.5 units on the STAIS-S scale after sensitivity analysis, suggesting a rather large meaningful effect size.31 Given we found a reduction of 1.65 points for each empathic response, however, with a range of 0-14 negative emotions expressed over a median 19-minute encounter, there is opportunity for hospitalists to achieve a clinically significant decrease in patient anxiety during an admission encounter. The potential to reduce anxiety is extended further when we consider that the impact of an empathic response may apply not just to the admission encounter alone but also to numerous other patient-clinician interactions over the course of a hospitalization.

A healthy body of communication research supports the associations we found in our study between empathy and patient ratings of communication and physicians. Families in ICU conferences rate communication more positively when physicians express empathy,12 and a number of studies indicate an association between empathy and patient satisfaction in outpatient settings.8 Given the associations we found with negative ratings on the items in our study, promoting empathic responses to expressions of emotion and, more importantly, stressing avoidance of nonempathic responses may be relevant efforts in working to improve patient satisfaction scores on surveys reporting “top box” percentages, such as Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS). More notably, evidence indicates that empathy has positive impacts beyond satisfaction surveys, such as adherence, better diagnostic and clinical outcomes, and strengthening of patient enablement.8Not all hospitalist responses to emotion were associated with patient ratings across the 7 communication items we assessed. For example, we did not find an association between how physicians responded to patient expressions of negative emotion and patient perception that enough time was spent in the visit or the degree to which talking with the doctor met a patient’s overall needs. It follows logically, and other research supports, that empathy would influence patient ratings of physician caring and trust,32 whereas other communication factors we were unable to measure (eg, physician body language, tone, and use of jargon and patient health literacy and primary language) may have a more significant association with patient ratings of the other items we assessed.

In considering the clinical application of our results, it is important to note that communication skills, including responding empathically to patient expressions of negative emotion, can be imparted through training in the same way as abdominal examination or electrocardiogram interpretation skills.33-35 However, training of hospitalists in communication skills requires time and some financial investment on the part of the physician, their hospital or group, or, ideally, both. Effective training methods, like those for other skill acquisition, involve learner-centered teaching and practicing skills with role-play and feedback.36 Given the importance of a learner-centered approach, learning would likely be better received and more effective if it was tailored to the specific needs and patient scenarios commonly encountered by hospitalist physicians. As these programs are developed, it will be important to assess the impact of any training on the patient-reported outcomes we assessed in this observational study, along with clinical outcomes.

Our study has several limitations. First, we were only able to evaluate whether hospitalists verbally responded to patient emotion and were thus not able to account for nonverbal empathy such as facial expressions, body language, or voice tone. Second, given our patient consent rate of 63%, patients who agreed to participate in the study may have had different opinions than those who declined to participate. Also, hospitalists and patients may have behaved differently as a result of being audio recorded. We only included patients who spoke English, and our patient population was predominately non-Hispanic white. Patients who spoke other languages or came from other cultural backgrounds may have had different responses. Third, we did not use a single validated scale for patient ratings of communication, and multiple analyses increase our risk of finding statistically significant associations by chance. The skewing of the communication rating items toward high scores may also have led to our results being driven by outliers, although the model we chose for analysis does penalize for this. Furthermore, our sample size was small, leading to wide CIs and potential for lack of statistical associations due to insufficient power. Our findings warrant replication in larger studies. Fourth, the setting of our study in an academic center may affect generalizability. Finally, the age of our data (collected between 2008 and 2009) is also a limitation. Given a recent focus on communication and patient experience since the initiation of HCAHPS feedback, a similar analysis of empathy and communication methods now may result in different outcomes.

In conclusion, our results suggest that enhancing hospitalists’ empathic responses to patient expressions of negative emotion could decrease patient anxiety and improve patients’ perceptions of (and thus possibly their relationships with) hospitalists, without sacrificing efficiency. Future work should focus on tailoring and implementing communication skills training programs for hospitalists and evaluating the impact of training on patient outcomes.