The Weekend Effect in Hospitalized Patients: A Meta-Analysis

BACKGROUND: The presence of a “weekend effect” (increased mortality rate during Saturday and/or Sunday admissions) for hospitalized inpatients is uncertain.

PURPOSE: We performed a systematic review to examine the presence of a weekend effect on hospital inpatient mortality.

DATA SOURCES: PubMed, EMBASE, SCOPUS, and Cochrane databases (January 1966–April 2013) were utilized for our search.

STUDY SELECTION: We examined the mortality rate for hospital inpatients admitted during the weekend compared with those admitted during the workweek. To be included, the study had to provide discrete mortality data around the weekends (including holidays) versus weekdays, include patients who were admitted as inpatients over the weekend, and be published in English.

DATA EXTRACTION: The primary outcome was all-cause weekend versus weekday mortality with subgroup analysis by personnel staffing levels, rates and times to procedures rates and delays, or illness severity.

DATA SYNTHESIS: A total of 97 studies (N = 51,114,109 patients) were examined. Patients admitted on the weekends had a significantly higher overall mortality (relative risk, 1.19; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-1.23). With regard to the subgroup analyses, patients admitted on the weekends consistently had higher mortality than those admitted during the week, regardless of the levels of weekend/weekday differences in staffing, procedure rates and delays, and illness severity.

CONCLUSIONS: Hospital inpatients admitted during weekends may have a higher mortality rate compared with inpatients admitted during the weekdays.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Data Synthesis and Analysis

We used a random effects meta-analysis approach for estimating an overall relative risk (RR) and risk differences of mortality for weekends versus weekdays, as well as subgroup specific estimates, and for computing confidence limits. The DerSimonian and Laird approach was used to estimate the random effects. Within each of the 4 subgroups (weekend staffing, procedure rates and delays, illness severity), we grouped each qualified individual study by the presence of a difference (ie, difference, no difference, or mixed) and then pooled the mortality rates for all of the studies in that group. For instance, in the subgroup of staffing, we sorted available studies by whether weekend staffing was the same or decreased versus weekday staffing, then pooled the mortality rates for studies where staffing levels were the same (versus weekday) and also separately pooled studies where staffing levels were decreased (versus weekday). Data were managed with Stata 13 (Stata Statistical Software: Release 13; StataCorp. 2013, College Station, TX) and R, and all meta-analyses were performed with the metafor package in R.15 Pooled estimated are presented as RR (95% confidence intervals [CI]).

RESULTS

A literature search retrieved a total of 594 unique citations. A review of the bibliographic references yielded an additional 20 articles. Upon evaluation, 97 studies (N = 51,114,109 patients) met inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The articles were published between 2001–2012; the kappa statistic comparing interrater reliability in the selection of articles was 0.86. Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 present a summary of study characteristics and outcomes of the accepted articles. A summary of accepted studies is in Supplementary Table 1. When summing the total number of subjects across all 97 articles, 76% were classified as weekday and 24% were weekend patients.

Weekend Admission/Inpatient Status and Mortality

The definition of the weekend varied among the included studies. The weekend time period was delineated as Friday midnight to Sunday midnight in 66% (65/99) of the studies. The remaining studies typically defined the weekend to be between Friday evening and Monday morning although studies from the Middle East generally defined the weekend as Wednesday/Thursday through Saturday. The definition of mortality also varied among researchers with most studies describing death rate as hospital inpatient mortality although some studies also examined multiple definitions of mortality (eg, 30-day all-cause mortality and hospital inpatient mortality). Not all studies provided a specific timeframe for mortality.

Fifty studies did not report a specific time frame for deaths. When a specific time frame for death was reported, the most common reported time frame was 30 days (n = 15 studies) and risk of mortality at 30 days still was higher for weekends (RR = 1.07; 95% CI,1.03-1.12; I2 = 90%). When we restricted the analysis to the studies that specified any timeframe for mortality (n = 49 studies), the risk of mortality was still significantly higher for weekends (RR = 1.12; 95% CI,1.09-1.15; I2 = 95%).

Weekend Effect Factors

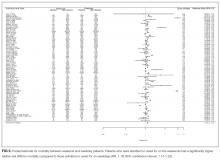

We also performed subgroup analyses to investigate the overall weekend effect by hospital level factors (weekend staffing, procedure rates and delays, illness severity). Complete data were not available for all studies (staffing levels = 73 studies, time to intervention = 18 studies, rate of intervention = 30 studies, illness severity = 64 studies). Patients admitted on the weekends consistently had higher mortality than those admitted during the week, regardless of the levels of weekend/weekday differences in staffing, procedure rates and delays, illness severity (Figure 3). Analysis of studies that included staffing data for weekends revealed that decreased staffing levels on the weekends was associated with a higher mortality for weekend patients (RR = 1.16; 95% CI, 1.12-1.20; I2 = 99%; Figure 3). There was no difference in mortality for weekend patients when staffing was similar to that for the weekdays (RR = 1.21; 95% CI, 0.91-1.63; I2 = 99%).

Analysis for weekend data revealed that longer times to interventions on weekends were associated with significantly higher mortality rates (RR = 1.11; 95% CI, 1.08-1.15; I2 = 0%; Figure 3). When there were no delays to weekend procedure/interventions, there was no difference in mortality between weekend and weekday procedures/interventions (RR = 1.04; 95% CI, 0.96-1.13; I2 = 55%; Figure 3). Some articles included several procedures with “mixed” results (some procedures were “positive,” while other were “negative” for increased mortality). In studies that showed a mixed result for time to intervention, there was a significant increase in mortality (RR = 1.16; 95% CI, 1.06-1.27; I2 = 42%) for weekend patients (Figure 3).

Analyses showed a higher mortality rate on the weekends regardless of whether the rate of intervention/procedures was lower (RR=1.12; 95% CI, 1.07-1.17; I2 = 79%) or the same between weekend and weekdays (RR = 1.08; 95% CI, 1.01-1.16; I2 = 90%; Figure 3). Analyses showed a higher mortality rate on the weekends regardless of whether the illness severity was higher on the weekends (RR = 1.21; 95% CI, 1.07-1.38; I2 = 99%) or the same (RR = 1.21; 95% CI, 1.14-1.28; I2 = 99%) versus that for weekday patients (Figure 3). An inverse funnel plot for publication bias is shown in Figure 4.