Things We Do For No Reason: Two-Unit Red Cell Transfusions in Stable Anemic Patients

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

The “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

INTRODUCTION

Blood transfusion is not only the most common procedure performed in US hospitals but is also widely overused, according to The Joint Commission. Unnecessary transfusions can increase risks and costs, and now, multiple landmark trials support using restrictive transfusion strategies. This manuscript discusses the importance and potential impacts of giving single-unit red blood cell (RBC) transfusions in anemic patients who are not actively bleeding and are hemodynamically stable. The “thing we do for no reason” is giving 2-unit RBC transfusions when 1 unit would suffice. We call this the “Why give 2 when 1 will do?” campaign for RBC transfusion.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 74-year-old, 70-kg male with a known history of myelodysplastic syndrome is admitted for dizziness and shortness of breath. His hemoglobin (Hb) concentration is 6.2 g/dL (baseline Hb of 8 g/dL). The patient denies any hematuria, hematemesis, and melena. Physical examination is remarkable only for tachycardia—heart rate of 110. The admitting hospitalist ponders whether to order a 2-unit red blood cell (RBC) transfusion.

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK DOUBLE UNIT RED BLOOD CELL TRANSFUSIONS ARE HELPFUL

RBC transfusion is the most common procedure performed in US hospitals, with about 12 million RBC units given to patients in the United States each year.1 Based on an opinion paper published in 1942 by Adams and Lundy2 the “10/30 rule” set the standard that the ideal transfusion thresholds were an Hb of 10 g/dL or a hematocrit of 30%. Until human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) became a threat to the nation’s blood supply in the early 1980s, few questioned the 10/30 rule. There is no doubt that blood transfusions can be lifesaving in the presence of active bleeding or hemorrhagic shock; in fact, many hospitals have blood donation campaigns reminding us to “give blood—save a life.” To some, these messages may suggest that more blood is better. Prior to the 1990s, clinicians were taught that if the patient needed an RBC transfusion, 2 units was the optimal dose for adult patients. In fact, single-unit transfusions were strongly discouraged, and authorities on the risks of transfusion wrote that single-unit transfusions were acknowledged to be unnecessary.3

WHY THERE IS “NO REASON” TO ROUTINELY ORDER DOUBLE UNIT TRANSFUSIONS

According to a recent Joint Commission Overuse Summit, transfusion was identified as 1 of the top 5 overused medical procedures.4 Blood transfusions can cause complications such as transfusion-related acute lung injury and transfusion-associated circulatory overload, the number 1 and 2 causes of transfusion-related deaths, respectively,5 as well as other transfusion reactions (eg, allergic and hemolytic) and alloimmunization. Transfusion-related morbidity and mortality have been shown to be dose dependent,6 suggesting that the lowest effective number of units should be transfused. Although, with modern-day testing, the risks of HIV and viral hepatitis are exceedingly low, emerging infectious diseases such as the Zika virus and Babesiosis represent new threats to the nation’s blood supply, with potential transfusion-related transmission and severe consequences, especially for the immunosuppressed. As quality-improvement, patient safety, and cost-saving initiatives, many hospitals have implemented strategies to reduce unnecessary transfusions and decrease overall blood utilization.

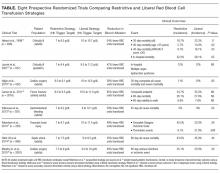

The above-mentioned studies support the concept that oftentimes less is more for transfusions, which includes giving the lowest effective amount of transfused blood. These trials have enrolled multiple patient populations, such as critically ill patients in the intensive care unit,11,13 elderly orthopedic surgery patients,14 cardiac surgery patients,12 and patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage,15 traumatic brain injury,17 and septicemia.16 Outcomes in the trials included mortality, serious infections, thrombotic and ischemic events, neurologic deficits, multiple-organ dysfunction, and inability to ambulate (Table). The findings in these studies suggest that we increase risks and cost without improving outcomes only by giving more blood than is necessary. Since most of these trials were published in the last decade, some very recently, clinicians have not fully adopted these newer, restrictive transfusion strategies.19