Internal Medicine Resident Engagement with a Laboratory Utilization Dashboard: Mixed Methods Study

The objective of this study was to measure internal medicine resident engagement with an electronic medical record-based dashboard providing feedback on their use of routine laboratory tests relative to service averages. From January 2016 to June 2016, residents were e-mailed a snapshot of their personalized dashboard, a link to the online dashboard, and text summarizing the resident and service utilization averages. We measured resident engagement using e-mail read-receipts and web-based tracking. We also conducted 3 hour-long focus groups with residents. Using grounded theory approach, the transcripts were analyzed for common themes focusing on barriers and facilitators of dashboard use. Among 80 residents, 74% opened the e-mail containing a link to the dashboard and 21% accessed the dashboard itself. We did not observe a statistically significant difference in routine laboratory ordering by dashboard use, although residents who opened the link to the dashboard ordered 0.26 fewer labs per doctor-patient-day than those who did not (95% confidence interval, −0.77 to 0.25; P = 0 .31). While they raised several concerns, focus group participants had positive attitudes toward receiving individualized feedback delivered in real time.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

RESULTS

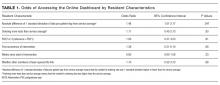

Eighty unique residents participated in the intervention, including 51 PGY1s (64%) and 29 PGY2- or PGY3-level (36%) residents. Of these, 19/80 (24%) physicians participated more than once. 74% of participants opened the e-mail and 21% opened the link to the dashboard. The average elapsed time from receiving the initial e-mail to logging into the dashboard was 28.5 hours (standard deviation [SD] = 25.7, median = 25.5, interquartile range [IQR] = 40.5). On average, residents deviated from the service mean by 0.54 laboratory test orders (SD = 0.49, median = 0.40, IQR = 0.60). The mean baseline rate of targeted labs was 1.30 (SD 1.77) labs per physician per patient-day.8

We did not observe a statistically significant difference in routine laboratory ordering by dashboard use, although residents who opened the link to the dashboard ordered 0.26 fewer labs per doctor-patient-day than those who did not (95% CI, −0.77-0.25; P = 0.31). The greatest difference was observed on day 2 after the intervention, when lab orders were lower among dashboard users by 0.59 labs per doc-patient-day (95% CI, −1.41-0.24; P = 0.16) when compared with the residents who did not open the dashboard.

Third, participants identified barriers to using dashboards during training, including time constraints, insufficient patient volume, possible unanticipated consequences, and concerns regarding punitive action by the hospital administration or teaching supervisors. Suggestions to improve the uptake of practice feedback via dashboards included additional guidance for interpreting the data, exclusion of outlier cases or risk-adjustment, and ensuring ease of access to the data.

Last, participants also expressed enthusiasm toward receiving other types of individualized feedback data, including patient satisfaction, timing of discharges, readmission rates, utilization of consulting services, length of stay, antibiotic stewardship practices, costs and utilization data, and mortality or intensive care unit transfer rates (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Overall, the engagement rates of internal medicine trainees with the online dashboard were low. Most residents did open the e-mails containing the link and basic information about their utilization rates, but less than a quarter of them accessed the dashboard containing real-time data. Additionally, on average, it took them more than a day to do so. However, there is some indication that residents who deviated further from the mean in either direction, which was described in the body of the e-mail, were more motivated to investigate further and click the link to access the dashboard. This suggests that providing practice feedback in this manner may be effective for a subset of residents who deviate from the “typical practice,” and as such, dashboards may represent a potential educational tool that could be aligned with practice-based learning competencies.

The focus groups provided important context about residents’ attitudes toward EMR-based dashboards. Overall, residents were enthusiastic about receiving information regarding their personal laboratory ordering, both in terms of preventing iatrogenic harm and waste of resources. This supports previous research that found that both medical students and residents overwhelmingly believe that the overuse of labs is a problem and that there may be insufficient focus on cost-conscious care during training.9,10 However, many residents questioned several aspects of the specific intervention used in this study and suggested that significant improvements would need to be made to future dashboards to increase their utility.

To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to evaluate resident engagement and attitudes toward receiving practice-based feedback via an EMR-based online dashboard. Previous efforts to influence resident laboratory ordering behavior have primarily focused on didactic sessions, financial incentives, price transparency, and repeated e-mail messaging containing summary statistics about ordering practices and peer comparisons.11-14 While some prior studies observed success in decreasing unnecessary use of laboratory tests, such efforts are challenging to implement routinely on a teaching service with multiple rotating providers and may be difficult to replicate. Future iterations of dashboards that incorporate focused curriculum design and active participation of teaching attendings require further study.

This study has several limitations. The sample size of physicians is relatively small and consists of residents at a single institution. This may limit the generalizability of the results. Additionally, the dashboard captured laboratory-ordering rates during a 2-week block on an inpatient medicine service and was not adjusted for factors such as patient case mix. However, the rates were adjusted for patient volume. In future iterations of utilization dashboards, residents’ concerns about small sample size and variability in clinical severity could be addressed through the adoption of risk-adjustment methodologies to balance out patient burden. This could be accomplished using currently available EMR data, such as diagnosis related groups or diagnoses codes to adjust for clinical complexity or report expected length of stay as a surrogate indicator of complexity.

Because residents are expected to be responsive to feedback, their use of the dashboards may represent an upper bound on physician responsiveness to social comparison feedback regarding utilization. However, e-mails alone may not be an effective way to provide feedback in areas that require additional engagement by the learner, especially given the volume of e-mails and alerts physicians receive. Future efforts to improve care efficiency may try to better capture baseline ordering rates, follow resident ordering over a longer period of time, encourage hospital staff to review utilization information with trainees, integrate dashboard information into regular performance reviews by the attendings, and provide more concrete feedback from attendings or senior residents for how this information can be used to adjust behavior.