Blood Products Provided to Patients Receiving Futile Critical Care

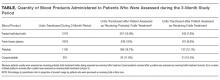

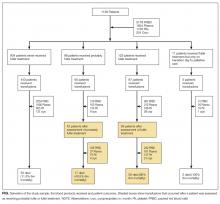

The number of hospitalized patients receiving treatment perceived to be futile is not insignificant. Blood products are valuable resources that are donated to help others in need. We aimed to quantify the amount of blood transfused into patients who were receiving treatment that the critical care physician treating them perceived to be futile. During a 3-month period, critical care physicians in 5 adult intensive care units completed a daily questionnaire to identify patients perceived as receiving futile treatment. Of 1136 critically ill patients, physicians assessed 123 patients (11%) as receiving futile treatment. Fifty-nine (48%) of the 123 patients received blood products after they were assessed to be receiving futile treatment: 242 units of packed red blood cells (PRBCs) (7.6% of all PRBC units transfused into critical care patients during the 3-month study period); 161 (9.9%) units of plasma, 137 (12.1%) units of platelets, and 21 (10.5%) units of cryoprecipitate. Explicit guidelines on the use of blood products should be developed to ensure that the use of this precious resource achieves meaningful goals.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

RESULTS

During the 3-month study period, 36 critical care clinicians in 5 ICUs provided care to 1193 adult patients. After excluding boarders in the ICUs and missed and invalid assessments, 6916 assessments were made on 1136 patients. Of these 1136 patients, 98 (8.6%) patients received probably futile treatment and 123 (11%) patients received futile treatment according to the physicians caring for them.

For patients who were never rated as receiving futile treatment, the in-hospital mortality was 4.6% and the 6-month mortality was 7.3%. On the contrary, 68% of the patients who were perceived to receive futile ICU treatment died before hospital discharge and 85% died within 6 months; survivors remained in severely compromised health states.3

DISCUSSION

Blood and blood products are donated resources. These biological products are altruistically given with the expectation that they will be used to benefit others.13 It is the clinicians’ responsibility to use these precious gifts to achieve the goals of medicine, which include curing, preserving function, and preventing clinical deterioration that has meaning to the patient. Our study shows that a small, but not insignificant, proportion of these donated resources are provided to hospitalized patients who are perceived as receiving futile critical care. That means that these transfusions are used as part of the critical care interventions that prolong the dying process and achieve outcomes, such as existence in coma, which few, if any, patients would desire. However, it should be noted that some of the health states preserved, such as neurological devastation or multi-organ failure with an inability to survive outside an ICU, were likely desired by patients’ families and might even have been desired by patients themselves. Whether blood donors would wish to donate blood to preserve life in such compromised health states is testable. This proportion of blood provided to ICU patients perceived as receiving futile treatment (7.6%) is similar to or greater than that lost due to wastage, which ranges from 0.1% to 6.7%.14 While the loss of this small proportion of blood products due to expiration or procedural issues is probably unavoidable, but should be minimized as much as possible, the provision of blood products to patients receiving futile critical care is under the control of the healthcare team. This raises the question of how altruistic blood donors would feel about donating if they were aware that 1 of every 13 units transfused in the ICU would be given to a patient that the physician feels will not benefit. In turn, it raises the question of whether the physician should refrain from using these blood products for patients who will not benefit in accordance with principles of evidence-based medicine, in order to ensure their availability for patients that will benefit.

This study has several limitations. Family/patient perspectives were not included in the assessment of futile treatment. It should also be recognized that the percentage of blood products provided to patients receiving inappropriate critical care is likely an underestimate as only blood product use during the 3-month study period was included, as many of these patients were admitted to the ICU prior the study period, and/or remained in the ICU or hospital after this window.

CONCLUSIONS

Similar to other treatments provided to patients who are perceived to receive futile critical care, blood products represent a healthcare resource that has the potential to be used without achieving the goals of medicine. But unlike many other medical treatments, the ability to maintain an adequate blood supply for transfusion relies on altruistic blood donors, individuals who are simply motivated by a desire to achieve a healthcare good.13 Explicit guidelines on the use of blood products should be developed to ensure that the use of this precious resource achieves meaningful goals. These goals need to be transparently defined such that a physician’s decision to not transfuse is expected as part of evidence-based medicine. Empiric research, educational interventions, and clearly delineated conflict-resolution processes may improve clinicians’ ability to handle these difficult cases.15