A Randomized Controlled Trial of a CPR Decision Support Video for Patients Admitted to the General Medicine Service

BACKGROUND: Patient preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) are important, especially during hospitalization when a patient’s health is changing. Yet many patients are not adequately informed or involved in the decision-making process.

OBJECTIVES: We examined the effect of an informational video about CPR on hospitalized patients’ code status choices.

DESIGN: This was a prospective, randomized trial conducted at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System in Minnesota.

PARTICIPANTS: We enrolled 119 patients, hospitalized on the general medicine service, and at least 65 years old. The majority were men (97%) with a mean age of 75.

INTERVENTION: A video described code status choices: full code (CPR and intubation if required), do not resuscitate (DNR), and do not resuscitate/do not intubate (DNR/DNI). Participants were randomized to watch the video (n = 59) or usual care (n = 60).

MEASUREMENTS: The primary outcome was participants’ code status preferences. Secondary outcomes included a questionnaire designed to evaluate participants’ trust in their healthcare team and knowledge and perceptions about CPR.

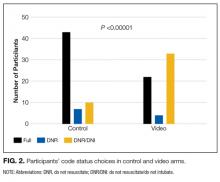

RESULTS: Participants who viewed the video were less likely to choose full code (37%) compared to participants in the usual care group (71%) and more likely to choose DNR/DNI (56% in the video group vs. 17% in the control group) (P < 0.00001). We did not see a difference in trust in their healthcare team or knowledge and perceptions about CPR as assessed by our questionnaire.

CONCLUSIONS: Hospitalized patients who watched a video about CPR and code status choices were less likely to choose full code and more likely to choose DNR/DNI.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

RESULTS

Study Participants

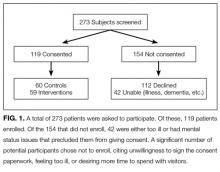

A total of 273 potentially eligible patients were approached to participate and 119 (44%) enrolled. (Figure 1). Of the 154 patients that were deemed eligible after initial screening, 42 patients were unable to give consent due to the severity of their illness or because of their mental status. Another 112 patients declined participation in the study, citing reasons such as disinterest in the consent paperwork, desire to spend time with visitors, and unease with the subject matter. Patients who declined participation did not differ significantly by age, sex, or race from those enrolled in the study.

Among the 119 participants, 60 were randomized to the control arm, and 59 were randomized to the intervention arm. Participants in the 2 arms did not differ significantly in age, sex, or race (P > 0.05), although all 4 women in the study were randomized to the intervention arm. Eighty-seven percent of the study population identified as white with the remainder including black, Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American, or declining to answer. The mean age was 75.8 years in the control arm vs. 75.2 years in the intervention arm.

Primary diagnoses in the study group ranged widely from relatively minor skin infections to acute pancreatitis. The control arm and the intervention arm did not differ significantly in the incidence of heart failure, pulmonary disease, renal dialysis, cirrhosis, stroke, or active cancer (P > 0.05). Patients were considered as having a stroke if they had suffered a stroke during their hospital admission or if they had long-term sequelae of prior stroke. Patients were considered as having active cancer if they were currently undergoing treatment or had metastases. Participants were considered as having multiple morbidities if they possessed 2 or more of the listed conditions. Between the control arm and the intervention arm, there was no significant difference in the number of participants with multiple morbidities (27% in the control group and 24% in the video group).

Code Status Preference

There was a significant difference in the code status preferences of the intervention arm and the control arm (P < 0.00001; Figure 2). In the control arm, 71% of participants chose full code, 12% chose DNR, and 17% chose DNR/DNI. In the intervention arm, only 37% chose full code, 7% chose DNR, and 56% chose DNR/DNI.

Secondary outcomes

Participants in the control and intervention arms were asked about their trust in their medical team (Question 1, Figure 3). There was no significant difference, but a trend towards less trust in the intervention group (P = 0.083) was seen with 93% of the control arm and 76% of the intervention arm agreeing with the statement “My doctors and healthcare team want what is best for me.”

Question 2, “If I choose to avoid resuscitation efforts, I will not receive care,” was designed to assess participants’ knowledge and perception about the care they would receive if they chose DNR/DNI as their code status. No significant difference was seen between the control and the interventions arms, with 28% of the control group agreeing with the statement, compared to 22% of the video group.

For question 3, participants were asked to respond to the statement “I would like to live as long as possible, even if I never leave the hospital.” No significant differences were seen between the control and the intervention arms, with 22% of both groups agreeing with the statement.

When we examined participant responses by the code status chosen, a significantly higher percentage of participants who chose full code agreed with the statement in question 3 (P = 0.0133). Of participants who chose full code, 27% agreed with the statement, compared to 18% of participants who chose DNR and 12% of participants who chose DNR/DNI. There was no significant difference (P > 0.05) between participant code status choice and either Question 1 or 2.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the effect of watching a video about CPR and intubation on the code status preferences of hospitalized patients. Participants who viewed a video about CPR and intubation were more likely to choose to forgo these treatments. Participants who chose CPR and intubation were more likely to agree that they would want to live as long as possible even if that time were spent in a medical setting.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the role of a video decision support tool about code choices in the general hospital population, regardless of prognosis. Previous work has trialed the use of video support tools in hospitalized patients with a prognosis of less than 1 year,15 patients admitted to the ICU,18 and outpatients with cancer18 and those with dementia.16 Unlike previous studies, our study included a variety of illness severity.

Discussions about resuscitation are important for all adults admitted to the hospital because of the unpredictable nature of illness and the importance of providing high-quality care at the end of life. A recent study indicates that in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest occurs in almost 1 per 1000 hospital days.19 These discussions are particularly salient for patients 65 years and older because of the higher incidence of death in this group. Inpatient admission is often a result of a change in health status, making it an important time for patients to reassess their resuscitation preferences based on their physical state and known comorbidities.

Video tools supplement the traditional code status discussion in several key ways. They provide a visual simulation of the procedures that occur during a typical resuscitation. These tools can help patients understand what CPR and intubation entail and transmit information that might be missed in verbal discussions. Visual media is now a common way for patients to obtain medical information20-22 and may be particularly helpful to patients who have low health literacy.23Video tools also help ensure that patients receive all the facts about resuscitation irrespective of how busy their provider may be or how comfortable the provider is with the topic. Lastly, video tools can reinforce information that is shared in the initial code status discussion. Given the significant differences in code status preference between our control and video arms, it is clear that the video tool has a significant impact on patient choices.

While we feel that our study clearly indicates the utility of video tools in code status discussion in hospitalized patients, there are some limitations. The current study enrolled participants who were predominantly white and male. All participants were recruited from the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Minnesota. The relatively homogenous study population may impact the study’s generalizability. Another potential limitation of our study was the large number of eligible participants who declined to participate (41%), with many citing that they did not want to sign the consent paperwork. Additionally, the study coordinator was not blinded to the randomization of the participants, which could result in ascertainment bias. Also of concern was a trend, albeit nonsignificant, towards less trust in the healthcare team in the video group. Because the study was not designed to assess trust in the healthcare team both before and after the intervention, it is unclear if this difference was a result of the video.

Another area of potential concern is that visual images can be edited to sway viewers’ opinions based on the way content is presented. In our video, we included input from palliative care and internal medicine specialists. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation and intubation were performed on a CPR mannequin. The risks and benefits of CPR and intubation were discussed, as were the implications of choosing DNR or DNR/DNI code statuses.

The questionnaire that we used to assess participants’ knowledge and beliefs about resuscitation showed no differences between the control and the intervention arms of the study. We were surprised that a significant number of participants in the intervention group agreed with the statement, “If I choose to avoid resuscitation efforts, I will not receive care.” Our video specifically addressed the common belief that choosing DNR/DNI or DNR code statuses means that a patient will not continue to receive medical care. It is possible that participants were confused by the way the question was worded or that they understood the question to apply only to care received after a cardiopulmonary arrest had occurred.

This study and several others14-16 show that the use of video tools impacts participants’ code status preferences. There is clinical and humanistic importance in helping patients make informed decisions regarding whether or not they would want CPR and/or intubation if their heart were to stop or if they were to stop breathing. The data suggest that video tools are an efficient way to improve patient care and should be made widely available.