The TEND (Tomorrow’s Expected Number of Discharges) Model Accurately Predicted the Number of Patients Who Were Discharged from the Hospital the Next Day

BACKGROUND: Knowing the number of discharges that will occur is important for administrators when hospital occupancy is close to or exceeds 100%. This information will facilitate decision making such as whether to bring in extra staff, cancel planned surgery, or implement measures to increase the number of discharges. We derived and internally validated the TEND (Tomorrow’s Expected Number of Discharges) model to predict the number of discharges from hospital in the next day.

METHODS: We identified all patients greater than 1 year of age admitted to a multisite academic hospital between 2013 and 2015. In derivation patients we applied survival-tree methods to patient-day covariates (patient age, sex, comorbidities, location, admission urgency, service, campus, and weekday) and identified risk strata having unique discharge patterns. Discharge probability in each risk strata for the previous 6 months was summed to calculate each day’s expected number of discharges.

RESULTS: Our study included 192,859 admissions. The daily number of discharges varied extensively (median 139; interquartile range [IQR] 95-160; range 39-214). We identified 142 discharge risk strata. In the validation patients, the expected number of daily discharges strongly predicted the observed number of discharges (adjusted R2 = 89.2%; P < 0.0001). The relative difference between observed and expected number of discharges was small (median 1.4%; IQR −5.5% to 7.1%).

CONCLUSION: The TEND model accurately predicted the daily number of discharges using information typically available within hospital data warehouses. Further study is necessary to determine if this information improves hospital bed management.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

RESULTS

There were 192,859 admissions involving patients more than 1 year of age that spent at least part of their hospitalization between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2015 (Table). Patients were middle-aged and slightly female predominant, with about half being admitted from the emergency department. Approximately 80% of admissions were to surgical or medical services. More than 95% of admissions ended with a discharge from the hospital with the remainder ending in a death. Almost 30% of hospitalization days occurred on weekends or holidays. Hospitalizations in the derivation (2013-2014) and validation (2015) group were essentially the same, except there was a slight drop in hospital length of stay (from a median of 4 days to 3 days) between the 2 periods.

Patient and hospital covariates importantly influenced the daily conditional probability of discharge (Figure 1). Patients admitted to the obstetrics/gynecology department were notably more likely to be discharged from hospital with no influence from the day of week. In contrast, the probability of discharge decreased notably on the weekends in the other departments. Patients on the ward were much more likely to be discharged than those in the intensive care unit, with increasing age associated with a decreased discharge likelihood in the former but not the latter patients. Finally, discharge probabilities varied only slightly between campuses at our hospital with discharge risk decreasing as severity of illness (as measured by LAPS) increased.

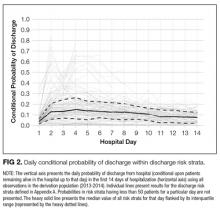

The TEND model contained 142 discharge risk strata (Appendix A). Weekend-holiday status had the strongest association with discharge probability (ie, it was the first splitting variable). The most complex discharge risk strata contained 6 covariates. The daily conditional probability of discharge during the first 2 weeks of hospitalization varied extensively between discharge risk strata (Figure 2). Overall, the conditional discharge probability increased from the first to the second day, remained relatively stable for several days, and then slowly decreased over time. However, this pattern and day-to-day variability differed extensively between risk strata.

The observed daily number of discharges in the validation cohort varied extensively (median 139; interquartile range [IQR] 95-160; range 39-214). The TEND model accurately predicted the daily number of discharges with the expected daily number being strongly associated with the observed number (adjusted R2 = 89.2%; P < 0.0001; Figure 3). Calibration decreased but remained significant when we limited the analyses by hospital campus (General: R2 = 46.3%; P < 0.0001; Civic: R2 = 47.9%; P < 0.0001; Heart Institute: R2 = 18.1%; P < 0.0001). The expected number of daily discharges was an unbiased estimator of the observed number of discharges (its parameter estimate in a linear regression model with the observed number of discharges as the outcome variable was 1.0005; 95% confidence interval, 0.9647-1.0363). The absolute difference in the observed and expected daily number of discharges was small (median 1.6; IQR −6.8 to 9.4; range −37 to 63.4) as was the relative difference (median 1.4%; IQR −5.5% to 7.1%; range −40.9% to 43.4%). The expected number of discharges was within 20% of the observed number of discharges in 95.1% of days in 2015.

DISCUSSION

Knowing how many patients will soon be discharged from the hospital should greatly facilitate hospital planning. This study showed that the TEND model used simple patient and hospitalization covariates to accurately predict the number of patients who will be discharged from hospital in the next day.

We believe that this study has several notable findings. First, we think that using a nonparametric approach to predicting the daily number of discharges importantly increased accuracy. This approach allowed us to generate expected likelihoods based on actual discharge probabilities at our hospital in the most recent 6 months of hospitalization-days within patients having discharge patterns that were very similar to the patient in question (ie, discharge risk strata, Appendix A). This ensured that trends in hospitalization habits were accounted for without the need of a period variable in our model. In addition, the lack of parameters in the model will make it easier to transplant it to other hospitals. Second, we think that the accuracy of the predictions were remarkable given the relative “crudeness” of our predictors. By using relatively simple factors, the TEND model was able to output accurate predictions for the number of daily discharges (Figure 3).

This study joins several others that have attempted to accomplish the difficult task of predicting the number of hospital discharges by using digitized data. Barnes et al.11 created a model using regression random forest methods in a single medical service within a hospital to predict the daily number of discharges with impressive accuracy (mean daily number of discharges observed 8.29, expected 8.51). Interestingly, the model in this study was more accurate at predicting discharge likelihood than physicians. Levin et al.12 derived a model using discrete time logistic regression to predict the likelihood of discharge from a pediatric intensive care unit, finding that physician orders (captured via electronic order entry) could be categorized and used to significantly increase the accuracy of discharge likelihood. This study demonstrates the potential opportunities within health-related data from hospital data warehouses to improve prediction. We believe that continued work in this field will result in the increased use of digital data to help hospital administrators manage patient beds more efficiently and effectively than currently used resource intensive manual methods.13,14

Several issues should be kept in mind when interpreting our findings. First, our analysis is limited to a single institution in Canada. It will be important to determine if the TEND model methodology generalizes to other hospitals in different jurisdictions. Such an external validation, especially in multiple hospitals, will be important to show that the TEND model methodology works in other facilities. Hospitals could implement the TEND model if they are able to record daily values for each of the variables required to assign patients to a discharge risk stratum (Appendix A) and calculate within each the daily probability of discharge. Hospitals could derive their own discharge risk strata to account for covariates, which we did not include in our study but could be influential, such as insurance status. These discharge risk estimates could also be incorporated into the electronic medical record or hospital dashboards (as long as the data required to generate the estimates are available). These interventions would permit the expected number of hospital discharges (and even the patient-level probability of discharge) to be calculated on a daily basis. Second, 2 potential biases could have influenced the identification of our discharge risk strata (Appendix A). In this process, we used survival tree methods to separate patient-days into clusters having progressively more homogenous discharge patterns. Each split was determined by using a proportional hazards model that ignored the competing risks of death in hospital. In addition, the model expressed age and LAPS as continuous variables, whereas these covariates had to be categorized to create our risk strata groupings. The strength of a covariate’s association with an outcome will decrease when a continuous variable is categorized.15 Both of these issues might have biased our final risk strata categorization (Appendix A). Third, we limited our model to include simple covariates whose values could be determined relatively easily within most hospital administrative data systems. While this increases the generalizability to other hospital information systems, we believe that the introduction of other covariates to the model—such as daily vital signs, laboratory results, medications, or time from operations—could increase prediction accuracy. Finally, it is uncertain whether or not knowing the predicted number of discharges will improve the efficiency of bed management within the hospital. It seems logical that an accurate prediction of the number of beds that will be made available in the next day should improve decisions regarding the number of patients who could be admitted electively to the hospital. It remains to be seen, however, whether this truly happens.

In summary, we found that the TEND model used a handful of patient and hospitalization factors to accurately predict the expected number of discharges from hospital in the next day. Further work is required to implement this model into our institution’s data warehouse and then determine whether this prediction will improve the efficiency of bed management at our hospital.