Can’t Shake This Feeling

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Lumbar puncture was performed. Opening pressure was 14.5 cm of water, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was clear and colorless. There were 3 red blood cells/mm 3 and no WBCs. Glucose level was 94 mg/dL, and protein level 74 mg/dL. CSF IgG synthesis rate was normal, flow cytometry revealed no abnormal clonal populations, and cytology was negative for malignancy. Two unique oligoclonal bands were found in the CSF.

The absence of WBCs in the CSF excludes CNS infection. The patient’s main problem is an inflammatory CNS process as defined by presence of oligoclonal bands in the CSF, compared with their absence in the serum. Autoimmune, neoplastic, and paraneoplastic disorders could explain these bands. There was no evidence of systemic autoimmune illness. The patient has not had a recent infection that could result in postinfectious demyelination, and her clinical and imaging features are not suggestive of a demyelinating disorder, such as multiple sclerosis. Of the neoplastic possibilities, lymphoma with CNS involvement may be difficult to detect initially; this diagnosis, however, is not supported by the unremarkable MRI, flow cytometry, and cytology findings. In paraneoplastic syndromes, the CSF may include antibodies that react to antigens in the brain or cerebellum.

At this point, evaluation for malignancy should involve mammography, imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, and colorectal screening. Testing should also include measurement of serum and CSF autoantibodies associated with paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration. The expanding list of paraneoplastic antibodies that may attack the cerebellum includes anti-Hu (often associated with small cell lung cancer), anti-Yo (associated with ovarian or breast cancer), anti-aquaporin 4, antibodies to the voltage-gated potassium channel, and anti–glutamic acid decarboxylase (anti-GAD).

Mammography and breast examination findings were normal. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest showed no adenopathy, nodules, or masses. Abdomen CT showed nonspecific prominence of the gallbladder wall. Flexible sigmoidoscopy revealed no masses, only thickened folds in the sigmoid colon; results of multiple colon biopsy tests were normal. Carcinoembryonic antigen level was 2.0 μg/L, and CA-125 level 5 U/mL. Serum GAD-65 antibodies were elevated (>30 nmol/L).

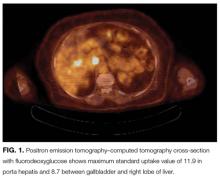

Anti-GAD is mostly known as the antibody associated with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). In rare instances, even in patients without a history of diabetes, anti-GAD antibodies may lead to an autoimmune attack on the brain, particularly the cerebellum, as part of an idiopathic autoimmune disorder or as a paraneoplastic syndrome. In either case, treatment involves corticosteroids, intravenous Ig, or plasma exchange. When the autoimmune attack is associated with malignancy, treatment response is poorer, unless the malignancy is successfully managed. The next steps are intravenous Ig or plasma exchange and positron emission tomography–CT (PET-CT) assessing for an underlying neoplasm that may have been too small to be detected with routine CT.

DISCUSSION

When clinical, MRI, and CSF findings suggest PNS, the next step in establishing the diagnosis is testing for neuronal antibodies. Testing should be performed for a comprehensive panel of antibodies in both serum and CSF.3,4 Testing for a single antibody can miss potential cases because various syndromes may be associated with multiple antibodies. In addition, presence of multiple antibodies (vs a single antibody) is a better predictor of cancer type.5,6 Sensitivity can be optimized by examining both serum and CSF, as in some cases, the antibody is identified in only one of these fluids.7,8 An identified antibody predicts the underlying malignancies most likely involved. For example, presence of anti-Hu antibodies is associated most often with small cell lung cancer, whereas presence of anti-Yo antibodies correlates with cancers of the breast, ovary, and lung. When the evaluation does not identify an underlying malignancy and PNS is suspected, PET-CT can be successfully used to detect an occult malignancy in 20% to 56% of patients.8-10

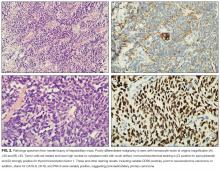

According to reports, at least 17 autoantibodies, including classic Purkinje cell cytoplasmic antibody type 1 (anti-Yo), antineuronal nuclear antibody type 1 (anti-Hu), and GAD-65 antibody, attack antigens in the cerebellum.11 GAD-65, an enzyme expressed in the brain and pancreatic β cells, is a soluble synaptic protein that produces the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-amino-butyric acid (GABA).12 Inhibition of GAD-65 in cerebellar tissue leads to decreased expression of GABA, resulting in extensive cerebellar deficits, such as those in the present case. Anti-GAD-65 antibodies have been associated with various disease processes. For example, anti-GAD-65 is found in the serum of 80% of patients with insulin-dependent T1DM.13 GAD-65 antibodies may also be detected in patients with stiff person syndrome (Table) and in patients with cerebellar ataxia caused by a paraneoplastic or autoimmune syndrome.14,15

Paraneoplastic anti-GAD cerebellar ataxia is very rare. It occurs at a median age of 60 years, affects men more often than women, and has an extremely poor prognosis.11,16 Underlying cancers identified in patients with this ataxia include solid organ tumors, lymphoma, and neuroendocrine carcinoma.17 The present case of anti-GAD-65 cerebellar ataxia is the first reported in a patient with biliary tract neuroendocrine carcinoma. Given the rarity of the disease and the advanced stage of illness when the condition is detected, optimal treatment is unknown. As extrapolated from management of other PNSs, recommended treatments are intravenous Ig, plasma exchange, steroids, and other immunosuppressants, as well as control of the underlying neoplasm.11

The discussant in this case couldn’t shake the feeling that there was more to the patient’s illness than statin or inflammatory myopathy. It was the patient’s shaking itself—the dysmetric limb and truncal titubation—that provided a clue to the cerebellar localization and ultimately led to the discovery of a paraneoplastic disorder linked to anatomically remote neuroendocrine cancer.