Impact of a Safety Huddle–Based Intervention on Monitor Alarm Rates in Low-Acuity Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Patients

BACKGROUND: Physiologic monitors generate high rates of alarms in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), yet few are actionable.

OBJECTIVE: To determine the association between a huddle-based intervention focused on reducing unnecessary alarms and the change in individual patients’ alarm rates in the 24 hours after huddles.

DESIGN: Quasi-experimental study with concurrent and historical controls.

SETTING: A 55-bed PICU.

PARTICIPANTS: Three hundred low-acuity patients with more than 40 alarms during the 4 hours preceding a safety huddle in the PICU between April 1, 2015, and October 31, 2015.

INTERVENTION: Structured safety huddle review and discussion of alarm causes and possible monitor parameter adjustments to reduce unnecessary alarms.

MAIN MEASUREMENTS: Rate of priority alarms per 24 hours occurring for intervention patients as compared with concurrent and historical controls. Balancing measures included unexpected changes in patient acuity and code blue events.

RESULTS: Clinicians adjusted alarm parameters in the 5 hours following the huddles in 42% of intervention patients compared with 24% of control patients (P = .002). The estimate of the effect of the intervention adjusted for age and sex compared with concurrent controls was a reduction of 116 priority alarms (95% confidence interval, 37-194) per 24 hours (P = .004). There were no unexpected changes in patient acuity or code blue events related to the intervention.

CONCLUSION: Integrating a data-driven monitor alarm discussion into safety huddles was a safe and effective approach to reducing alarms in low-acuity, high-alarm PICU patients. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12:652-657. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Human Subjects Protection

The Institutional Review Board of The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia approved this study with a waiver of informed consent.

Alarm Capture

We used BedMasterEx (Excel Medical Electronics; Jupiter, FL, https://excel-medical.com/products/bedmaster-ex) software connected to the General Electric monitor network to measure alarm rates. The software captured, in near real time, every alarm that occurred on every monitor in the PICU. Alarm rates over the preceding 4 hours for all PICU patients were exported and summarized by alarm type and level as set by hospital policy (crisis, warning, advisory, and system warning). Crisis and warning alarms were included as they represented potential life-threatening events meeting the definition of priority alarms. Physicians used an order within the PICU admission order-set to order monitoring based on preset age parameters (see online Appendix 1 for default settings). Physician orders were required for nurses to change alarm parameters. Daily electrode changes to reduce false alarms were standard of care.

Primary Outcome

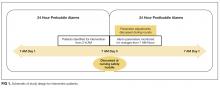

The primary outcome was the change in priority alarm activation rate (the number of priority alarms per day) from prehuddle period (24 hours before morning huddle) to posthuddle period (the 24 hours following morning huddle) for intervention cases as compared with controls.

Primary Intervention

The intervention consisted of integrating a short script to facilitate the discussion of the alarm data during existing safety huddle and rounding workflows. The discussion and subsequent workflow proceeded as follows: A member of the research team who was not involved in patient care brought an alarm data sheet for each randomly selected intervention patient on the east wing to each safety huddle. The huddles were attended by the outgoing night charge nurse, the day charge nurse, and all bedside nurses working on the east wing that day. The alarm data sheet provided to the charge nurse displayed data on the 1 to 2 alarm parameters (respiratory rate, heart rate, or pulse oximetry) that generated the highest number of alarms. The charge nurse listed the high-alarm patients by room number during huddle, and the alarm data sheet was given to the bedside nurse responsible for the patient to facilitate further scripted discussion during bedside rounds with patient-specific information to reduce the alarm rates of individual patients throughout the adjustment of physiologic monitor parameters (see Appendix 2 for sample data sheet and script).

Data Collection

Intervention patients were high-alarm, low-acuity patients on the east wing from June 1, 2015, through October 31, 2015. Two months of baseline data were gathered prior to intervention on all 3 wings; therefore, control patients were high-alarm, low-acuity patients throughout the PICU from April 1, 2015, to May 31, 2015, as historical controls and from June 1, 2015, to October 31, 2015, as concurrent controls. Alarm rates for the 24 hours prior to huddle and the 24 hours following huddle were collected and analyzed. See Figure 1 for schematic of study design.

We collected data on patient characteristics, including patient location, age, sex, and intervention date. Information regarding changes to monitor alarm parameters for both intervention and control patients during the posthuddle period (the period following morning huddle until noon on intervention day) was also collected. We monitored for code blue events and unexpected changes in acuity until discharge or transfer out of the PICU.

Data Analysis

We compared the priority alarm activation rates of individual patients in the 24 hours before and the 24 hours after the huddle intervention and contrasted the differences in rates between intervention and control patients, both concurrent and historical controls. We also divided the intervention and control groups into 2 additional groups each—those patients whose alarm parameters were changed, compared with those whose parameters did not change. We evaluated for possible contamination by comparing alarm rates of historical and concurrent controls, as well as evaluating alarm rates by location. We used mixed-effects regression models to evaluate the effect of the intervention and control type (historical or concurrent) on alarm rates, adjusted for patient age and sex. Analysis was performed using Stata version 10.3 (StataCorp, LLC, College Station, TX) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

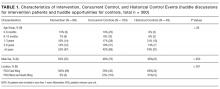

Because patients could be enrolled more than once, we refer to the instances when they were included in the study as “events” (huddle discussions for intervention patients and huddle opportunities for controls) below. We identified 49 historical control events between April 1, 2015, and May 31, 2015. During the intervention period, we identified 88 intervention events and 163 concurrent control events between June 1, 2015, and October 31, 2015 (total n = 300; see Table 1 for event characteristics). A total of 6 patients were enrolled more than once as either intervention or control patients.