We Want to Know: Eliciting Hospitalized Patients’ Perspectives on Breakdowns in Care

BACKGROUND: There is increasing recognition that patients have critical insights into care experiences, including breakdowns in care. Harnessing patient perspectives for hospital improvement requires an in-depth understanding of the types of breakdowns patients identify and the impact of these events.

METHODS: We interviewed a broad sample of patients during hospitalization and postdischarge to elicit patient perspectives on breakdowns in care. Through an iterative process, we developed a categorization of patient-perceived breakdowns called the Patient Experience Coding Tool.

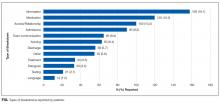

RESULTS: Of 979 interviewees, 386 (39.4%) believed they had experienced at least one breakdown in care. The most common reported breakdowns involved information exchange (n = 158, 16.1%), medications (n = 120, 12.3%), delays in admission (n = 90, 9.2%), team communication (n = 65, 6.6%), providers’ manner (n = 62, 6.3%), and discharge (n = 56, 5.7%). Of the 386 interviewees who reported a breakdown, 140 (36.3%) perceived associated harm. Patient-perceived harms included physical (eg, pain), emotional (eg, distress, worry), damage to relationship with providers, need for additional care or prolonged hospital stay, and life disruption. We found higher rates of reporting breakdowns among younger (<60 years old) patients (45.4% vs 34.5%, P < 0.001), those with at least some college education (46.8% vs 32.7%, P < 0.001), and those with another person (family or friend) present during the interview or interviewed in lieu of the patient (53.4% vs 37.8%, P = 0.002).

CONCLUSIONS: When asked directly, almost 4 out of 10 hospitalized patients reported a breakdown in their care. Patient-perceived breakdowns in care are frequently associated with perceived harm, illustrating the importance of detecting and addressing these events. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12:603-609. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

RESULTS

A total of 979 outreach interviews were conducted. Of these, 349 were conducted via telephone postdischarge, and 630 were conducted in person during hospitalization. The average interview duration was 8.5 minutes for telephone interviews and 12.2 minutes for in-person interviews. Of the patients approached to participate, 67% completed an interview (61% in person, 83% via telephone). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Overall, 386 of 979 interviewees (39.4%) believed they had experienced at least one breakdown in care. The types of patient-perceived breakdowns reported were categorized using the PECT and are summarized in Table 3 and the Figure. The most common concern involved information exchange. Approximately 1 in 10 patients (n = 105, 10.7%) felt that they had not received the information they needed when they needed it. Medication-related concerns were reported by 12.3% (n = 120) of interviewees and predominantly included concerns about what medications were being administered (5.7%) and inadequately treated pain (5.6%). Many of the patients expressing concerns about what medications were administered questioned why they were not receiving their outpatient medications or did not understand why a different medication was being administered, suggesting that many of these instances were related to breakdowns in communication as well. Other relatively common concerns were delays in the admissions process (reported by 9.2% of interviewees), poor team communication (reported by 6.6% of interviewees), healthcare providers with a rude or uncaring manner (reported by 6.3% of interviewees), and problems related to discharge (reported by 5.7% of interviewees).

Of the 386 interviewees who perceived a breakdown in care, 140 (36.3%) perceived harm associated with the event (Table 3). The most common harms were physical (eg, pain; n = 66) and emotional (eg, distress, worry; n = 60). In addition, patients reported instances of damage to relationships with providers (n = 28) resulting in a loss of trust, with participants citing breakdowns as a reason for not coming back to a particular hospital or provider. In other cases, patients believed that breakdowns in care resulted in the need for additional care or a prolonged hospital stay.

We found no difference between the 2 hospitals where the study was conducted in the percentage of interviewees reporting at least 1 breakdown (39.1% vs 39.9%, P = 0.80). We also found no difference between interview method, (ie, in person vs telephone; 40.6% vs 37.2%, respectively, P = 0.30), patient gender (40.6% and 38.8% for men and women, respectively, P = 0.57), race (41.0% and 36.8% for white and black or African-American, respectively, P = 0.20) or between interviewers (P = 0.37). We did identify differences in rates of reporting at least 1 breakdown in care related to age (45.4% of patients aged 60 years or younger vs 34.5% of patients older than 60 years, P < 0.001) and education (32.7% of patients with a high school education or less vs 46.8% of those with at least some college education, P < 0.001). Patients interviewed alone reported fewer breakdowns than if another person was present during the interview or was interviewed in lieu of the patient (37.8% vs 53.4%, P = 0.002). The rate of reporting breakdowns for patients interviewed alone in the hospital is very similar to the rates of those interviewed via telephone (37.8% vs 37.2%). For most types of breakdowns, there were no differences in reporting for in-person vs postdischarge interviews. Discharge-related problems were more frequently reported among patients interviewed postdischarge (8.9% postdischarge vs 4.0% in person, P = 0.002). Patients interviewed in person were more likely to report problems with information exchange compared to patients interviewed postdischarge (17.6% vs 13.5%, respectively; P = 0.09), although this did not reach statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

Through interviews with nearly 1000 patients, we have found that approximately 4 in 10 hospitalized patients believed they experienced a breakdown in care. Not only are patient-perceived breakdowns in care distressingly common, more than one-third of these events resulted in harm according to the patient. Patients reported a diverse range of breakdowns, including problems related to patient experience, as well as breakdowns in technical aspects of medical care. Collectively, these findings illustrate a striking need to identify and address these frequent and potentially harmful breakdowns.

Our findings are consistent with prior studies in which 20% to 50% of patients identified a problem during hospitalization. For example, Weingart et al. interviewed patients in a single general medical unit and found that 20% experienced an adverse event, near miss, or medical error, while nearly 40% experienced what was defined as a service quality incident.2,12 Of note, both our study and the study by Weingart et al. systematically elicited patients’ perspectives of breakdowns in care with explicit questions about problems or breakdowns in care.2,12 Because patients are often reluctant to speak up about problems in care,without such efforts to actively identify problems, providers and leaders are likely to be unaware of the majority of these concerns.6-8 These findings suggest that hospital-based providers should at least consider routinely asking patients about breakdowns in care to identify and respond to patients’ concerns.

Not only are patient-perceived breakdowns common, more than one-third of patients who experienced a breakdown considered it to be harmful. This suggests that our outreach approach identified predominantly nontrivial concerns. We adopted a broad definition of harm that includes emotional distress, damage to the relationship with providers, and life disruption. This differs from other studies examining patient reports of breakdowns in care, in which harm was restricted to physical injury.1,2 We consider this inclusive definition of harm to be a strength of the present study as it provides the most complete picture of the impact of such events on patients. This approach is supported by other studies demonstrating that patients place great emphasis on the psychological consequences of adverse events.17-19 Thus, it is clear from our work and other studies that nonphysical harm is important and warrants concerted efforts to address.

Patients in our study reported a variety of breakdowns, including breakdowns related to patient experience (eg, communication, relationship with providers) and technical aspects of healthcare delivery (eg, diagnosis, treatment). This is consistent with other studies examining patient perspectives of breakdowns in care. Weingart et al.found that hospitalized patients reported a broad range of problems, including adverse events, medical errors, communication breakdowns, and problems with food.2,12 This variety of events suggests a need for integration between the various hospital groups that handle patient-perceived breakdowns, including bedside providers, risk management, patient relations, patient advocates, and quality and safety groups, in order to provide a coordinated and effective response to the full spectrum of patient-perceived breakdowns in care.

Patients in our study were more likely to report breakdowns related to communication and relationships with providers than those related to technical aspects of care. Similarly, Kuzel et al.found that the most common problems cited by patients in the primary care setting were breakdowns in the clinician-patient relationship and access-related problems.17This is not surprising, as patients are likely to have more direct knowledge about communication and interpersonal relationships than about technical aspects of care.

We identified several factors associated with the likelihood of reporting a breakdown in care. Most strikingly, involving a friend or family member in the interview was strongly associated with reporting a breakdown. Other work has also suggested that patients’ friends and family members are an important source of information about safety concerns.20,21 In addition, several patient characteristics were associated with an increased likelihood of reporting a breakdown, including being younger and better educated. These findings highlight the importance of engaging patients’ friends and families in efforts to elicit patient concerns about healthcare, and they confirm recommendations for patients to bring a friend or family member to healthcare encounters.22 In addition, they illustrate the need to better understand how patient characteristics affect perceptions of breakdowns in care and their willingness to speak up, as this could inform efforts to target outreach to especially vulnerable patients.

A strength of this study is the number of interviews completed (almost 1000), which provides a diverse range of patient views and experiences, as evidenced by the demographic characteristics of participants. Interviews were conducted at two hospitals that differ substantially with regard to populations served, further enhancing the generalizability of our findings. Despite the large number of interviews and diverse patient characteristics, patients were drawn from only 3 units at 2 hospitals, which may limit generalizability.

We did not conduct medical record reviews to validate patients’ reports of problems, which may be viewed as a limitation. While such a comparison would be informative, the intent of the current study was to elicit patients’ perceptions of care, including aspects of care that are not typically captured in the medical record, such as communication. Other studies have demonstrated that patients’ reports of medical errors and adverse events tend to differ from providers’ reports of the same subjects.19,23 Therefore, we considered the patients’ perceptions of care to be a useful endpoint in and of itself. We did not determine the extent to which providers were already aware of patients’ concerns or whether they considered patients’ concerns valid. A related limitation is our inability to determine whether the differences we identified in the rates of breakdown reporting based on patient characteristics reflect differences in willingness to report or differences in experiences. Because we included patients in an MSU, it is possible that breakdowns were related to medical care, surgical care, or both. We did not follow patients longitudinally and therefore only captured harm perceived by a patient at the time of the interview. It is possible that patients may have experienced harm later in their hospitalization or following discharge that was not measured. Lastly, we did not measure interrater reliability of the interview coding and therefore do not present the PECT as a validated instrument. These important questions should be targeted for future study.