Hot in the tropics

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

DISCUSSION

When residents or visitors to tropical or sub-tropical regions, those located near or between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, present with fever, physicians usually first think of infectious diseases. This patient’s case is a reminder that these important first considerations should not be the last.

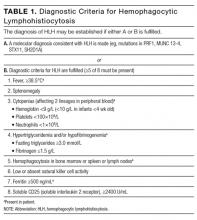

Generating a differential diagnosis for tropical illnesses begins with the patient’s history. Factors to be considered include location (regional disease prevalence), exposures (food/water ingestion, outdoor work/recreation, sexual contact, animal contact), and timing (temporal relationship of symptom development to possible exposure). Common tropical infections are malaria, dengue, typhoid, and emerging infections such as chikungunya, avian influenza, and Zika virus infection.1This case underscores the need to analyze diagnostic tests critically. Interpreting tests as simply positive or negative, irrespective of disease features, epidemiology, and test characteristics, can contribute to diagnostic error. For example, the patient’s positive ASO titer requires an understanding of disease features and a nuanced interpretation based on the clinical presentation. The erythematous posterior oropharynx prompted concern for postinfectious sequelae of streptococcal pharyngitis, but his illness was more severe and more prolonged than is typical of that condition. The isolated elevated O tsutsugamushi IgG titer provides an example of the role of epidemiology in test interpretation. Although a single positive value might indicate a new exposure for a visitor to an endemic region, IgG seropositivity in Singapore, where scrub typhus is endemic, likely reflects prior exposure to the organism. Diagnosing an acute scrub typhus infection in a patient in an endemic region requires PCR testing. The skin biopsy results highlight the importance of understanding test characteristics. A skin biopsy specimen must be adequate in order to draw valid and accurate conclusions. In this case, the initial skin biopsy was superficial, and the specimen inadequate, but the test was not “negative.” In the diagnostic skin biopsy, deeper tissue was sampled, and panniculitis (inflammation of subcutaneous fat), which arises in inflammatory, infectious, traumatic, enzymatic, and malignant conditions, was identified. An adequate biopsy specimen that contains subcutaneous fat is essential in making this diagnosis.2This patient eventually manifested several elements of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), a syndrome of excessive inflammation and resultant organ injury relating to abnormal immune activation and excessive inflammation. HLH results from deficient down-regulation of activated macrophages and lymphocytes.3 It was initially described in pediatric patients but is now recognized in adults, and associated with mortality as high as 50%.3 A high ferritin level (>2000 ng/mL) has 70% sensitivity and 68% specificity for pediatric HLH and should trigger consideration of HLH in any age group.4 The diagnostic criteria for HLH initially proposed in 2004 by the Histiocyte Society to identify patients for recruitment into a clinical trial included molecular testing consistent with HLH and/or 5 of 8 clinical, laboratory, or histopathologic features (Table 1).5 HScore is a more recent validated scoring system that predicts the probability of HLH (Table 2). A score above 169 signifies diagnostic sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 86%.6

The diagnosis of HLH warrants a search for its underlying cause. Common triggers are viral infections (eg, EBV), autoimmune diseases (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus), and hematologic malignancies. These triggers typically stimulate or suppress the immune system. Initial management involves treatment of the underlying trigger and, potentially, immunosuppression with high

In this case, SPTCL triggered HLH. SPTCL is a rare non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterized by painless subcutaneous nodules or indurated plaques (panniculitis-like) on the trunk or extremities, constitutional symptoms, and, in some cases, HLH.7-10 SPTCL is diagnosed by deep skin biopsy, with immunohistochemistry showing CD8-positive pathologic T cells expressing cytotoxic proteins (eg, granzyme B).9,11 SPTCL can either have an alpha/beta T-cell phenotype (SPTCL-AB) or gamma/delta T-cell phenotype (SPTCL-GD). Seventeen percent of patients with SPTCL-AB and 45% of patients with SPTCL-GD have HLH on diagnosis. Concomitant HLH is associated with decreased 5-year survival.12This patient presented with fevers and was ultimately diagnosed with HLH secondary to SPLTCL. His case is a reminder that not all diseases in the tropics are tropical diseases. In the diagnosis of a febrile illness, a broad evaluative framework and rigorous test results evaluation are essential—no matter where a patient lives or visits.KEY TEACHING POINTS

- A febrile illness acquired in the tropics is not always attributable to a tropical infection.

- To avoid diagnostic error, weigh positive or negative test results against disease features, patient epidemiology, and test characteristics.

- HLH is characterized by fevers, cytopenias, hepatosplenomegaly, hyperferritinemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypofibrinogenemia. In tissue specimens, hemophagocytosis may help differentiate HLH from competing conditions.

- After HLH is diagnosed, try to determine its underlying cause, which may be an infection, autoimmunity, or a malignancy (commonly, a lymphoma).