Telemetry monitor watchers reduce bedside nurses’ exposure to alarms by intercepting a high number of nonactionable alarms

Cardiac telemetry, designed to monitor hospitalized patients with active cardiac conditions, is highly utilized outside the intensive care unit but is also resource-intensive and produces many nonactionable alarms. In a hospital setting in which dedicated monitor watchers are set up to be the first responders to system-generated alerts, we conducted a retrospective study of the alerts produced over a continuous 2-month period to evaluate how many were intercepted before nurse notification for being nonactionable, and how many resulted in code team activations. Over the 2-month period, the system generated 20,775 alerts (5.1/patient-day, on average), of which 87% were intercepted by monitor watchers. None of the alerts for asystole, ventricular fibrillation, or ventricular tachycardia resulted in a code team activation. Our results highlight the high burden of alerts, the large majority of which are nonactionable, as well as the role of monitor watchers in decreasing the alarm burden on nurses. Measures are needed to decrease telemetry-related alerts in order to reduce alarm-related harms, such as alarm fatigue. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12:447-449. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

RESULTS

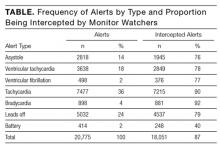

Within the 2-month study period, there were 1917 admissions to, and 1370 transfers to, non-ICU floors, for a total of 3287 unique patient-admissions and 9704 total patient-days. There were 1199 patient admissions with telemetry orders (36.5% of all admissions), 4044 total patient-days of telemetry, and an average of 66.3 patients monitored per day. In addition, the system generated 20,775 alerts, an average of 341 per day, 5.1 per patient-day, 1 every 4 minutes. Overall, 18,051 alerts (87%) were intercepted by monitor watchers, preventing nurse text-alarms. Of all alerts, 91% were from patients on medicine services, including pulmonary and cardiology; 6% were from patients on the neurology floor; and 3% were from patients on the surgery floor.

Forty percent of all alerts were for heart rates deviating outside the ranges set by the provider; of these, the overwhelming majority were intercepted as nuisance alerts (Table). In addition, 26% of all alerts were for maintenance reasons, including issues with batteries or leads. Finally, 34% (6954) were suspected lethal alerts (asystole, VT/VF); of these, 74% (5170) were intercepted by monitor watchers, suggesting they were deemed invalid. None of the suspected lethal alerts triggered a code team activation, indicating there were no telemetry-documented asystole or VT/VF episodes prompting resuscitative efforts. During the study period, there were 7 code team activations. Of the 7 patients, 2 were on telemetry, and their code team activation was for hypoxia detected by pulse oximetry; the other 5 patients, not on telemetry, were found unresponsive or apneic, and 4 of them had confirmed pulseless electrical activity.

DISCUSSION

In small studies, other investigators have directly observed nurses for hours at a time and assessed their response to telemetry-related alarms. 1,2 In the present study, we found a very large number of telemetry-detected alerts over a continuous 2-month period. The large majority (87%) of alerts were manually intercepted by monitor watchers before being communicated to a nurse or provider, indicating these alerts did not affect clinical management and likely were either false positives or nonactionable. It is possible that repeat nonactionable alerts, like continued sinus tachycardia or bradycardia, affect decision making, but this may be outside the role of continuous cardiac telemetry. In addition, it is likely that all the lethal alarms (asystole, VT/VF) forwarded to the nurses were invalid, as none resulted in code team activations.

Addressing these alerts is a major issue, as frequent telemetry alarms can lead to alarm fatigue, a widely acknowledged safety concern. 6 Furthermore, nonactionable alarms are a time sink, diverting nursing attention from other patient care needs. Finally, nonactionable alarms, especially invalid alarms, can lead to adverse patient outcomes. Although we did not specifically evaluate for harm, an earlier case series found a potential for unnecessary interventions and device implantation as a result of reporting artifactual arrhythmias. 7

Our results also highlight the role of monitor watchers in intercepting nonactionable alarms and reducing the alarm burden on nurses. Other investigators have reported on computerized paging systems that directly alert only nurses, 8 or on escalated alarm paging systems that let noncrisis alarms self-resolve. 9 In contrast, our study used a hybrid 2-step telemetry-monitoring system—an escalated paging system designed to be sensitive and less likely than human monitoring to overlook events, followed by dedicated monitor watchers who are first-responders for a large number of alarms and who increase the specificity of alarms by screening for nonactionable alarms, thereby reducing the number of alarms transmitted to nurses. We think that, for most hospitals, monitor watchers are cost-effective, as their hourly wage is lower than that of registered nurses. Furthermore, monitor watchers can screen alerts faster because they are always at the monitoring station. Their presence reduces the amount of time that nurses need to divert from other clinical tasks in order to walk to the monitoring station to evaluate alerts.

Nonetheless, there remains a large number of nonactionable alerts forwarded as alarms to nurses, likely because of monitor watchers’ inability to address the multitude of alerts, and perhaps because of alarm fatigue. Although this study showed the utility of monitor watchers in decreasing telemetry alarms to nurses, other steps can be taken to reduce telemetry alarm fatigue. A systematic review of alarm frequency interventions 5 noted that detection algorithms can be improved to decrease telemetry alert false positives. Another solution, likely easier to implement, is to encourage appropriate alterations in telemetry alarm parameters, which can decrease the alarm proportion. 10 An essential step is to decrease inappropriate telemetry use regarding the indication for and duration of monitoring, as emphasized by the Choosing Wisely campaign championing American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for appropriate telemetry use. 11 At our institution, 20.2% of telemetry orders were for indications outside AHA guidelines, and that percentage likely is an underestimate, as this was required self-reporting on ordering. 12 Telemetry may not frequently result in changes in management in the non-ICU setting, 13 and may lead to other harms such as worsening delirium, 14 so it needs to be evaluated for harm versus benefit per patient before order.

Cardiac telemetry in the non-ICU setting produces a large number of alerts and alarms. The vast majority are not seen or addressed by nurses or physicians, leading to a negligible impact on patient care decisions. Monitor watchers reduce the nursing burden in dealing with telemetry alerts, but we emphasize the need to take additional measures to reduce telemetry-related alerts and thereby reduce alarm-related harms and alarm fatigue.