Prospective cohort study of hospitalized adults with advanced cancer: Associations between complications, comorbidity, and utilization

BACKGROUND

Inpatient hospital stays account for more than a third of direct medical cancer care costs. Evidence on factors driving these costs can inform planning of services, as well as consideration of equity in access.

OBJECTIVE

To measure the association between hospital costs, and demographic, clinical, and system factors, for a cohort of adults with advanced cancer.

DESIGN

Prospective multisite cohort study.

SETTING

Four medical and cancer centers.

PATIENTS

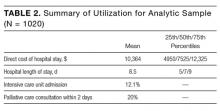

Adults with advanced cancer admitted to a participating hospital between 2007 and 2011, excluding those with dementia. Final analytic sample included 1020 patients.

METHODS

With receipt of palliative care controlled for, the associations between hospital cost and patient factors were estimated. Factors covered the domains of demographics (age, sex, race), socioeconomics and systems (education, insurance, living will, proxy), clinical care (diagnoses, complications deemed to pose a threat to life or bodily functions, comorbidities, symptom burden, activities of daily living), and prior healthcare utilization (home help, analgesic prescribing).

OUTCOME MEASURE

Direct hospital costs.

RESULTS

A major (markedly abnormal) complication (+$8267; P < 0.01), a minor but not a major complication (+$5289; P < 0.01), and number of comorbidities (+$852; P < 0.01) were associated with higher cost, and admitting diagnosis of electrolyte disorders (–$4759; P = 0.01) and increased age (–$53; P = 0.03) were associated with lower cost.

CONCLUSIONS

Complications and comorbidity burden drive inhospital utilization for adults with advanced cancer. There is little evidence of sociodemographic associations and no apparent impact of advance directives. Attempts to control growth of hospital cancer costs require consideration of how the most resource-intensive patients are identified promptly and prioritized for cost-effective care. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12:407-413. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

All 4 of these high-volume tertiary-care medical centers were selected for their high patient volume (to facilitate sample size) and research capacity (to facilitate proficient recruitment and data collection). Before the study was initiated, it was approved by the institutional review board of each facility. In addition, approval was sought from each attending physician at each hospital site; patients whose physician did not grant approval were not considered for enrollment. More than 95% of physicians gave their approval.

Patients were at least 18 years old and had a primary diagnosis of metastatic solid tumor; central nervous system malignancy; locally advanced head, neck, or pancreas cancer; metastatic melanoma; or transplant-ineligible lymphoma or multiple myeloma. Patients were excluded if they did not speak English, had a diagnosis of dementia, were unresponsive or nonverbal, had been admitted for routine chemotherapy, died or were discharged within 48 hours of admission, or had had a previous palliative care consultation.

Eligible patients were identified through daily review of admissions records and administrative databases. For each potential study patient identified, that patient’s bedside nurse inquired about willingness to participate in the study. Then, for each willing patient, a trained clinical interviewer approached to explain the study and obtain informed consent. With the patient’s consent, family members were also approached and enrolled with written informed consent.

Quantitative Variables

Independent variables. In the dataset, we identified 17 patient-level variables we hypothesized could be significantly associated with hospitalization cost. These variables covered 4 domains:

- Demographics: age, sex, race.

- Socioeconomics/systems: education level, insurance status, presence of advance directive (living will or healthcare proxy).

- Clinical care: primary cancer diagnosis, admitting diagnosis, comorbidities (Elixhauser index22), symptom burden and severity (Condensed Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale [CMSAS]23), and activities of daily living24 or presence of a hospital-acquired condition or complication.25

- Prior utilization: visiting homecare nurse and home health aide within 2 weeks before admission, and analgesic use in morphine sulfate equivalents within week before admission.

Data were collected through a combination of medical record review (age, sex, diagnoses, comorbidities, complications), patient interview (race, education, advance directive, CMSAS, activities of daily living, prior utilization), and hospital administrative databases (insurance). For use in regression, variables were divided into categories when appropriate. Table 1 lists these predictors and their prevalence in the analytic sample.

Dependent variable. The outcome of interest in this analysis was total direct cost of hospital stay. Direct costs are those attributable to the care of a specific patient, as distinct from indirect costs, the shared overhead costs of running a hospital.26 Cost data were extracted from hospital accounting databases and therefore reflect actual costs, the US dollar cost to the hospitals of care provided, also known as direct measurement.27 Costs were standardized for geographical region using the Medicare Wage Index28 and year using the Consumer Price Index29 and are presented here in US dollars for 2011, the final year of data collection.

Statistical Methods

Primary analyses. We regressed total direct hospital costs against all predictors listed in Table 1. To control for receipt of palliative care, we used additional independent variables—a fixed-effects variable for each of 3 hospitals (the fourth hospital was used as the reference case) and a binary treatment variable (whether or not the patient was seen by a palliative care consultation team within 2 days of hospital admission).19,20

Associations between cost and patient-level covariates were derived with use of a generalized linear model with a γ distribution and a log link,30 selected after comparative evaluation of performance for multiple linear and nonlinear modeling options.31

For each patient-level covariate, we estimated average marginal effects. For continuous variables, we estimated the marginal increase in cost associated with a 1-unit increase in the variable. For binary variables, we estimated the average incremental effect, the increase in cost associated with a move from the reference group, holding all other covariates to their original values. All analyses were performed with Stata Version 12.32

Secondary analyses. Primary analyses showed that number of patient comorbidities (Elixhauser index) was strongly associated with complications and comorbidity count. Prior analyses with these data have shown that palliative care had a larger cost-saving effect for patients with a larger number of comorbidities.20 Additional analyses were therefore performed to examine associations between complications, utilization, and palliative care. First, we cross-tabulated the sample by complications status (none; minor or major) and receipt of timely palliative care, and we present their summary utilization data. Second, we estimated the effect for each complications stratum (none; minor or major) of receiving timely palliative care on cost. These estimates are calculated consistent with prior work with these data: We used propensity scores to balance patients who received the treatment (palliative care) with patients who did not (usual care only),33,34 and we used a generalized linear model with a γ distribution and a log link to regress the direct hospital care cost on the binary treatment variable and all predictors listed in Table 1.19-21