Postdischarge clinics and hospitalists: A review of the evidence and existing models

Over the past 10 years, postdischarge clinics have been introduced in response to various health system pressures, including the focus on rehospitalizations and the challenges of primary care access. Often ignored in the discussion are questions of the effect of postdischarge physician visits on readmissions. In addition, little attention has been given to other clinical outcomes, such as reducing preventable harm and mortality. A review of dedicated, hospitalist-led postdischarge clinics, of the data supporting postdischarge physician visits, and of the role of hospitalists in these clinics may be instructive for hospitalists and health systems considering the postdischarge clinic environment. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12:467-471. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Comprehensive High-Risk Patient Solutions

At the other end of the clinic spectrum are more integrated postdischarge approaches, which also evolved from the hospitalist model with hospitalist staffing. However, these approaches were introduced in response to the clinical needs of the highest risk patients (who are most vulnerable to frequent provider transitions), not to a systemic inability to provide routine postdischarge care.30

The most long-standing model for this type of clinic is represented by CareMore Health System, a subsidiary of Anthem.30-32 The extensivist, an expanded-scope hospitalist, acts as primary care coordinator, coordinating a multidisciplinary team for a panel of about 100 patients, representing the sickest 5% of the Medicare Advantage–insured population. Unlike the traditional hospitalist, the extensivist follows patients across all care sites, including hospital, rehabilitation sites, and outpatient clinic. For the most part, this relationship is not designed to evolve into a longitudinal relationship, but rather is an intervention only for the several-months period of acute need. Internal data have shown effects on hospital readmissions as well as length of stay.30

Another integrated clinic was established in 2013, at the University of Chicago. This was an effort to redesign care for patients at highest risk for hospitalization.33 Similar to the CareMore process, a high-risk population is identified by prior hospitalization and expected high Medicare costs. A comprehensive care physician cares for these patients across care settings. The clinic takes a team-based approach to patient care, with team members selected on the basis of patient need. Physicians have panels limited to only 200 patients, and generally spend part of the day in clinic, and part in seeing their hospitalized patients. Although reminiscent of a traditional primary care setting, this clinic is designed specifically for a high-risk, frequently hospitalized population, and therefore requires physicians with both a skill set akin to that of hospitalists, and an approach of palliative care and holistic patient care. Outcomes from this trial clinic are expected in 2017 or 2018.

LOGISTICAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR DISCHARGE CLINICS

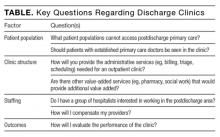

Considering some key operational questions (Table) can help guide hospitals, hospitalists, and healthcare systems as they venture into the postdischarge clinic space. Return on investment and sustainability are two key questions for postdischarge clinics.

Return on investment varies by payment structure. In capitated environments with a strong emphasis on readmissions and total medical expenditure, a successful postdischarge clinic would recoup the investment through readmission reduction. However, maintaining adequate patient volume against high no-show rates may strain the group financially. In addition, although a hospitalist group may reap few measurable benefits from this clinical exposure, the unique view of the outpatient world afforded to hospitalists working in this environment could enrich the group as a whole by providing a more well-rounded vantage point.

Another key question surrounds sustainability. The clinic at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston temporarily closed due to high inpatient volume and corresponding need for those hospitalists in the inpatient setting, early in its inception. It subsequently closed due to evolution in the clinic where it was based, rendering it unnecessary. Clinics that are contingent on other clinics will be vulnerable to external forces. Finally, staffing these clinics may be a stretch for a hospitalist group, as a partly different skill set is required for patient care in the outpatient setting. Hospitalists interested in care transitions are well suited for this role. In addition, hospitalists interested in more clinical variety, or in more schedule variety than that provided in a traditional hospitalist schedule, often enjoy the work. A vast majority of hospitalists think PCPs are responsible for postdischarge problems, and would not be interested in working in the postdischarge world.34 A poor fit for providers may lead to clinic failure.

As evident from this review, gaps in understanding the benefits of postdischarge care have persisted for 10 years. Discharge clinics have been scantly described in the literature. The primary unanswered question remains the effect on readmissions, but this has been the sole research focus to date. Other key research areas are the impact on other patient-centered clinical and system outcomes (eg, patient satisfaction, particularly for patients seeing new providers), postdischarge mortality, the effect on other adverse events, and total medical expenditure.

The healthcare system is evolving in the context of a focus on readmissions, primary care access challenges, and high-risk patients’ specific needs. These forces are spurring innovation in the realm of postdischarge physician clinics, as even the basic need for an appointment may not be met by the existing outpatient primary care system. In this context, multiple new outpatient care structures have arisen, many staffed by hospitalists. Some, such as clinics based in safety net hospitals and academic medical centers, address the simple requirement that patients who lack easy access, because of insurance status or provider availability, can see a doctor after discharge. This type of clinic may be an essential step in alleviating a strained system but may not represent a sustainable long-term solution. More comprehensive solutions for improving patient care and clinical outcomes may be offered by integrated systems, such as CareMore, which also emerged from the hospitalist model. A lasting question is whether these clinics, both the narrowly focused and the comprehensive, will have longevity in the evolving healthcare market. Inevitably, though, hospitalist directors will continue to raise such questions, and should stand to benefit from the experiences of others described in this review.