Acute pain management in hospitalized adult patients with opioid dependence: a narrative review and guide for clinicians

Pain management is a core competency of hospital medicine, and effective acute pain management should be a goal for all hospital medicine providers. The prevalence of opioid use in the United States, both therapeutic and non-medical in origin, has dramatically increased over the past decade. Although nonopioid medications and nondrug treatments are essential components of managing all acute pain, opioids continue to be the mainstay of treatment for severe acute pain in both opioid-naïve and opioid-dependent patients. In this review, we provide an evidence-based approach to appropriate and safe use of opioid analgesics in treating acute pain in hospitalized patients who are opioid-dependent. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12:375-379. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

The effect of tolerance also contributes to the pathophysiology of opioid abuse as it leads to a decrease in opioid potency with repeated administration.14-16 To achieve analgesia as well as the reward effect, opioid dosage and/or frequency must be increased, strengthening the association between receipt of opioid and reward. Tolerance to the reward effect occurs quickly, whereas tolerance to respiratory depression occurs much more slowly.17 This mismatch in tolerance of effect may lead to increase in opioid doses to maintain analgesia or euphoria, and also places patients at a higher risk of overdose.18

ACUTE PAIN MANAGEMENT

Clinical Example: Heroin User

A 47-year-old man is admitted with fever, chills, and severe mid-back pain and receives a diagnosis of sepsis. The patient admits to using intravenous heroin 500 mg (five 100 mg “bags”) on a daily basis. He is admitted, fluid resuscitated and started on broad spectrum antibiotics. Blood cultures quickly grow Staphylococcus aureus. Magnetic resonance imaging of the spine shows cervical vertebral osteomyelitis. On examination, the patient is diaphoretic and complains of diffuse myalgias and diarrhea. The patient’s back pain is so severe that he cannot ambulate. What is the best way to manage this patient’s acute pain and communicate with him about his pain management?

Managing acute pain in a patient using heroin can be challenging for many reasons. First, both physicians and pharmacists report a lack of confidence in their ability to prescribe opioids safely or to treat patients with a history of opioid abuse.19 Second, there is a paucity of evidence in treating acute pain in heroin users. Finally, due to the clandestine manufacturing of illicit drugs, the actual purity of the drug is often unknown making it difficult to assess the dose of opioids in heroin users. Drug Enforcement Agency seizure data indicate a wide range of heroin purity: 30% to 70%.20

In the hospital setting, acute pain is often undertreated in patients with a history of active opioid abuse. This may be due to providers’ misconceptions regarding pain and behavior in opioid addicts, including worrying that the patient’s pain is exaggerated in order to obtain drugs, thinking that a regular opioid habit eliminates pain, believing that opioid therapy is not effective in drug addicts, or worrying that prescribing opioids will exacerbate drug addiction.21 Data demonstrates that the presence of opioid addiction seems to worsen the experience of acute pain.22 These patients also often have a higher tolerance and thus require higher dosages and more frequent dosing of opioids to adequately treat their pain.23

Converting daily heroin use to morphine equivalents is necessary to establish a baseline analgesic requirement and to prevent withdrawal. It is challenging to convert illicit heroin to morphine equivalents however, as one must take into account the wide variation in purity and understand that the stated use of heroin (e.g. 500 mg daily) reflects weight and not dosage of heroin.20

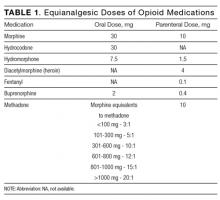

In these patients, treatment of acute pain should be individualized according to presenting illness and comorbidities. Previous data and an average purity of 40% suggest that the parenteral morphine equivalent to a bag of heroin (100 mg) is 15 to 30 mg.20,24,25 Common equianalgesic doses of opioid medications are listed in Table 1. Because of increased tolerance, the frequency of administration should be shortened, from every 4 hours to every 2 or 3 hours. Except for a shorter onset of action, there has not been a difference shown in superiority between oral and parenteral routes of administration. Finally, patients should receive both long-acting basal and short-acting as-needed analgesics based on their daily use of opioids.23

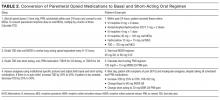

In our clinical example, IV heroin 500 mg daily converts to parenteral morphine 75 to 150 mg every 24 hours. We recommend initiating IV morphine 10 mg every 3 hours as needed for pain and withdrawal symptoms, with early reassessment regarding need for a higher dose or a shorter frequency based on symptoms. Nonopioid analgesics should also be administered with the goal of decreasing the opioid requirement. As soon as possible, the patient should be changed to oral basal and short-acting opioids as needed for breakthrough pain. The appropriate dose of long acting basal analgesia can be determined the following day based on the patient’s total daily dose (TDD) of opioids. An example of converting from intravenous PRN morphine to oral basal and short acting opioids is shown in Table 2.

In communicating with a patient with opioid-use disorder with acute pain, it is best to outline the pain management plan at admission including: the plan to effectively treat the patient’s acute pain, prevent opioid withdrawal symptoms, change to oral opioid analgesics as soon as possible, discussion of non-opioid and non-drug treatments, reinforcement that opioids will be tapered as the acute pain episode resolves, and a detailed plan for discharge Later in this article, we describe discharge planning.