Inpatient management of opioid use disorder: A review for hospitalists

The United States is experiencing an epidemic of nonmedical opioid use and opioid overdose-related deaths. As a result, there have been a number of public health interventions aimed at addressing this epidemic. However, these interventions fail to address care of individuals with opioid use disorder during hospitalizations and, therefore, miss a key opportunity for intervention. The role of hospitalists in managing hospitalized patients with opioid use disorder is not established. In this review, we discuss the inpatient management of individuals with opioid use disorder, including the treatment of withdrawal, benefits of medication-assisted treatment, and application of harm-reduction strategies. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12:369-374. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

The Future of Medication-Assisted Treatment

Currently, MAT is initiated and managed by outpatient addiction specialists. However, evidence supports initiation of MAT as an inpatient.48 A recent study compared inpatient buprenorphine detoxification to inpatient buprenorphine induction, dose stabilization, and postdischarge linkage-of-care to outpatient opioid treatment clinics. Patients who received inpatient buprenorphine initiation and linkage-of-care had improved buprenorphine treatment retention and reported less illicit opioid use.48 The development of partnerships between hospitals, inpatient clinicians, and outpatient addiction specialists is essential and could lead to significant advances in treating hospitalized patients with OUD.

The initiation of MAT in hospitalized patients with immediate linkage-of-care shows great promise; however, at this point, the initiation of MAT should be done only in conjunction with addiction specialists in patients with confirmed outpatient follow-up. In cases where inpatient MAT initiation is pursued, education of staff including nurses and pharmacists is essential.

Harm Reduction Interventions

Ideally, management of OUD results in abstinence from opioid misuse; however, some individuals are not ready for treatment or, despite MAT, have relapses of opioid misuse. Given this, a secondary goal in the management of OUD is the reduction of harm that can result from opioid misuse.

Many individuals inject opioids, which is associated with increased rates of viral and bacterial infections secondary to nonsterile injection practices.49 Educating patients on sterile injection methods (Table 2),50 including the importance of sterile-injecting equipment and water, and cleaning the skin prior to injection, may mitigate the risk of infections and should be provided for all hospitalized people who inject drugs.

Syringe-exchange programs provide sterile-injecting equipment in exchange for used needles, with a goal of increasing access to sterile supplies and removing contaminated syringes from circulation.51 While controversial, these programs may reduce the incidence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B virus.51

In addition, syringe-exchange programs often provide addiction treatment referrals, counseling, testing, and prevention education for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C virus, and sexually transmitted infections.49 In the United States, there are 226 programs in 33 states (see https://nasen.org/directory for a list of programs and locations. Inpatient clinicians should provide a list of local resources including syringe-exchange programs at the time of discharge for any people who inject drugs. In addition, individuals with OUD are at increased risk for overdose, especially in the postdischarge setting due to decreased opioid tolerance.52 In 2014, there were 28,647 opioid overdose-related deaths in the United States.2 To address this troubling epidemic, opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution has been championed to educate patients at risk of opioid overdose and potential first responders on how to counteract an overdose by using naloxone, an opioid antagonist (see Table 2 for more information on opioid overdose education). The use of opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution has been observed to reduce opioid overdose-related death rates.53

Hospitalists should provide opioid overdose education and naloxone to all individuals at risk of opioid overdose (including those with OUD), as well as potential first responders where the law allows (more information including individual state laws can be found at https://prescribetoprevent.org).20

Considerations at Discharge

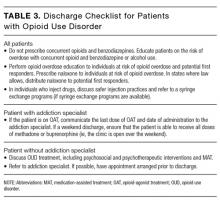

There are a number of considerations for the hospitalist at discharge (see Table 3 for a recommended discharge checklist). In addition, it is important to appreciate, and minimize, the ways that hospitalists contribute to the opioid epidemic. For instance, prescribing opioids at discharge in opioid-naïve patients increases the risk of chronic opioid use.54 It is also essential to recognize that increased doses of opioids are associated with increased rates of opioid overdose-related deaths.55 As such, hospitalists should maximize the use of nonopioid analgesics, prescribe opioids only when necessary, use the smallest effective dose of opioids, limit the number of opioid pills distributed to patients, and check prescription-monitoring programs for evidence of misuse.

CONCLUSION

Hospitalization serves as an important opportunity to address addiction in individuals with OUD. In addressing addiction, hospitalists should identify and intervene on psychosocial and mental health barriers, treat opioid withdrawal, and propagate harm reduction strategies. In addition, there is a growing role for hospitalists to be involved in the initiation of MAT and linkage-of-care to outpatient addiction treatment. If hospitalists become leaders in the inpatient management of OUD, they will significantly improve the care provided to this vulnerable patient population.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial conflicts of interest.