Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of hospital-acquired anemia

BACKGROUND

Although hypothesized to be a hazard of hospitalization, it is unclear whether hospital-acquired anemia (HAA) is associated with increased adverse outcomes following discharge.

OBJECTIVE

To examine the incidence, predictors, and postdischarge outcomes associated with HAA.

DESIGN

Observational cohort study using electronic health record data.

SUBJECTS

Consecutive medicine discharges between November 1, 2009 and October 30, 2010 from 6 Texas hospitals, including safety-net, teaching, and nonteaching sites. Patients with anemia on admission or missing hematocrit values at admission or discharge were excluded.

MEASURES

HAA was defined using the last hematocrit value prior to discharge and categorized by severity. The primary outcome was a composite of 30-day mortality and nonelective readmission.

RESULTS

Among 11,309 patients, one-third developed HAA (21.6% with mild HAA; 10.1% with moderate HAA; and 1.4% with severe HAA). The 2 strongest potentially modifiable predictors of developing moderate or severe HAA were length of stay (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 1.26 per day; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.23-1.29) and receipt of a major procedure (adjusted OR, 5.09; 95% CI, 3.79-6.82). Patients without HAA had a 9.7% incidence for the composite outcome versus 16.4% for those with severe HAA. Severe HAA was independently associated with a 39% increase in the odds for 30-day readmission or death (95% CI, 1.09-1.78). Most patients with severe HAA (85%) underwent a major procedure, had a discharge diagnosis of hemorrhage, and/or a discharge diagnosis of hemorrhagic disorder.

CONCLUSIONS

Severe HAA is associated with increased odds for 30-day mortality and readmission after discharge; however, it is uncertain whether severe HAA is preventable. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12:317-322. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Predictors of HAA

Compared to no or mild HAA, female sex, elective admission status, serum creatinine on admission, BUN to creatinine ratio greater than 20 to 1, hospital LOS, and undergoing a major diagnostic or therapeutic procedure were predictors for the development of moderate or severe HAA (Table 2). The model explained 23% of the variance (McFadden’s pseudo R2).

Incidence of Postdischarge Outcomes by Severity of HAA

The severity of HAA was associated with a dose-dependent increase in the incidence of 30-day adverse outcomes, such that patients with increasing severity of HAA had greater 30-day composite, mortality, and readmission outcomes (P < 0.001; Figure). The 30-day postdischarge composite outcome was primarily driven by hospital readmissions given the low mortality rate in our cohort. Patients who did not develop HAA had an incidence of 9.7% for the composite outcome, whereas patients with severe HAA had an incidence of 16.4%. Among the 24 patients with severe HAA but who had not undergone a major procedure or had a discharge diagnosis for hemorrhage or for a coagulation or hemorrhagic disorder, only 3 (12.5%) had a composite postdischarge adverse outcome (2 readmissions and 1 death). The median time to readmission was similar between groups, but more patients with severe HAA had an early readmission within 7 days of hospital discharge than patients who did not develop HAA (6.9% vs. 2.9%, P = 0.001; Supplemental Table 2).

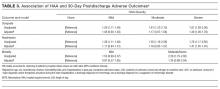

Association of HAA and Postdischarge Outcomes

In unadjusted analyses, compared to not developing HAA, mild, moderate, and severe HAA were associated with a 29%, 61%, and 81% increase in the odds for a composite outcome, respectively (Table 3). After adjustment for confounders, the effect size for HAA attenuated and was no longer statistically significant for mild and moderate HAA. However, severe HAA was significantly associated with a 39% increase in the odds for the composite outcome and a 41% increase in the odds for 30-day readmission (P = 0.008 and P = 0.02, respectively).

In sensitivity analyses, the exclusion of individuals who received at least 1 blood transfusion during the index hospitalization (n=298) and individuals who had a primary discharge diagnosis for AMI (n=353) did not substantively change the estimates of the association between severe HAA and postdischarge outcomes (Supplemental Tables 3 and 4). However, because of the fewer number of adverse events for each analysis, the confidence intervals were wider and the association of severe HAA and the composite outcome and readmission were no longer statistically significant in these subcohorts.

DISCUSSION

In this large and diverse sample of medical inpatients, we found that HAA occurs in one-third of adults with normal hematocrit value at admission, where 10.1% of the cohort developed moderately severe HAA and 1.4% developed severe HAA by the time of discharge. Length of stay and undergoing a major diagnostic or therapeutic procedure were the 2 strongest potentially modifiable predictors of developing moderate or severe HAA. Severe HAA was independently associated with a 39% increase in the odds of being readmitted or dying within 30 days after hospital discharge compared to not developing HAA. However, the associations between mild or moderate HAA with adverse outcomes were attenuated after adjusting for confounders and were no longer statistically significant.

To our knowledge, this is the first study on the postdischarge adverse outcomes of HAA among a diverse cohort of medical inpatients hospitalized for any reason. In a more restricted population, Salisbury et al.3 found that patients hospitalized for AMI who developed moderate to severe HAA (hemoglobin value at discharge of 11 g/dL or less) had greater 1-year mortality than those without HAA (8.4% vs. 2.6%, P < 0.001), and had an 82% increase in the hazard for mortality (95% confidence interval, hazard ratio 1.11-2.98). Others have similarly shown that HAA is common among patients hospitalized with AMI and is associated with greater mortality.5,9,18 Our study extends upon this prior research by showing that severe HAA increases the risk for adverse outcomes for all adult inpatients, not only those hospitalized for AMI or among those receiving blood transfusions.

Despite the increased harm associated with severe HAA, it is unclear whether HAA is a preventable hazard of hospitalization, as suggested by others.6,8 Most patients in our cohort who developed severe HAA underwent a major procedure, had a discharge diagnosis for hemorrhage, and/or had a discharge diagnosis for a coagulation or hemorrhagic disorder. Thus, blood loss due to phlebotomy, 1 of the more modifiable etiologies of HAA, was unlikely to have been the primary driver for most patients who developed severe HAA. Since it has been estimated to take 15 days of daily phlebotomy of 53 mL of whole blood in females of average body weight (and 20 days for average weight males) with no bone marrow synthesis for severe anemia to develop, it is even less likely that phlebotomy was the principal etiology given an 8-day median LOS among patients with severe HAA.19,20 However, since the etiology of HAA can be multifactorial, limiting blood loss due to phlebotomy by using smaller volume tubes, blood conservation devices, or reducing unnecessary testing may mitigate the development of severe HAA.21,22 Additionally, since more than three-quarters of patients who developed severe HAA underwent a major procedure, more care and attention to minimizing operative blood loss could lessen the severity of HAA and facilitate better recovery. If minimizing blood loss is not feasible, in the absence of symptoms related to anemia or ongoing blood loss, randomized controlled trials overwhelmingly support a restrictive transfusion strategy using a hemoglobin value threshold of 7 mg/dL, even in the postoperative setting.23-25

The implications of mild to moderate HAA are less clear. The odds ratios for mild and moderate HAA, while not statistically significant, suggest a small increase in harm compared to not developing HAA. Furthermore, the upper boundary of the confidence intervals for mild and moderate HAA cannot exclude a possible 30% and 56% increase in the odds for the 30-day composite outcome, respectively. Thus, a better powered study, including more patients and extending the time interval for ascertaining postdischarge adverse events beyond 30 days, may reveal a harmful association. Lastly, our study assessed only the association of HAA with 30-day readmission and mortality. Examining the association between HAA and other patient-centered outcomes such as fatigue, functional impairment, and prolonged posthospitalization recovery time may uncover other important adverse effects of mild and moderate HAA, both of which occur far more frequently than severe HAA.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, although we included a diverse group of patients from a multihospital cohort, generalizability to other settings is uncertain. Second, as this was a retrospective study using EHR data, we had limited information to infer the precise mechanism of HAA for each patient. However, procedure codes and discharge diagnoses enabled us to assess which patients underwent a major procedure or had a hemorrhage or hemorrhagic disorder during the hospitalization. Third, given the relatively few number of patients with severe HAA in our cohort, we were unable to assess if the association of severe HAA differed by suspected etiology. Lastly, because we were unable to ascertain the timing of the hematocrit values within the first 24 hours of admission, we excluded both patients with preexisting anemia on admission and those who developed HAA within the first 24 hours of admission, which is not uncommon.26 Thus, we were unable to assess the effect of acute on chronic anemia arising during hospitalization and HAA that develops within the first 24 hours, both of which may also be harmful.18,27,28

In conclusion, severe HAA occurs in 1.4% of all medical hospitalizations and is associated with increased odds of death or readmission within 30 days. Since most patients with severe HAA had undergone a major procedure or had a discharge diagnosis of hemorrhage or a coagulation or hemorrhagic disorder, it is unclear if severe HAA is potentially preventable through preventing blood loss from phlebotomy or by reducing iatrogenic injury during procedures. Future research should assess the potential preventability of severe HAA, and examine other patient-centered outcomes potentially related to anemia, including fatigue, functional impairment, and trajectory of posthospital recovery.