Automating venous thromboembolism risk calculation using electronic health record data upon hospital admission: The automated Padua Prediction Score

BACKGROUND

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk scores assist providers in determining the relative benefit of prophylaxis for individual patients. While automated risk calculation using simpler electronic health record (EHR) data is feasible, it lacks clinical nuance and may be less predictive. Automated calculation of the Padua Prediction Score (PPS), requiring more complex input such as recent medical events and clinical status, may save providers time and increase risk score use.

OBJECTIVE

We developed the Automated Padua Prediction Score (APPS) to auto-calculate a VTE risk score using EHR data drawn from prior encounters and the first 4 hours of admission. We compared APPS to standard practice of clinicians manually calculating the PPS to assess VTE risk.

DESIGN

Cohort study of 30,726 hospitalized patients. APPS was compared to manual calculation of PPS by chart review from 300 randomly selected patients.

MEASUREMENTS

Prediction of hospital-acquired VTE not present on admission.

RESULTS

Compared to manual PPS calculation, no significant difference in average score was found (5.5 vs. 5.1, P = 0.073), and area under curve (AUC) was similar (0.79 vs. 0.76). Hospital-acquired VTE occurred in 260 (0.8%) of 30,726 patients. Those without VTE averaged APPS of 4.9 (standard deviation [SD], 2.6) and those with VTE averaged 7.7 (SD, 2.6). APPS had AUC = 0.81 (confidence interval [CI], 0.79-0.83) in patients receiving no pharmacologic prophylaxis and AUC = 0.78 (CI, 0.76-0.82) in patients receiving pharmacologic prophylaxis.

CONCLUSION

Automated calculation of VTE risk had similar ability to predict hospital-acquired VTE as manual calculation despite differences in how often specific scoring criteria were considered present by the 2 methods. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12:231-237. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Statistical Analysis

For the 75 randomly selected cases of presumed hospital-acquired VTE, the number of cases was chosen by powering our analysis to find a difference in proportion of 20% with 90% power, α = 0.05 (two-sided). We conducted χ2 tests on the entire study cohort to determine if there were significant differences in demographics, LOS, and incidence of hospital-acquired VTE by prophylaxis received. For both the pharmacologic and the no pharmacologic prophylaxis groups, we conducted 2-sample Student t tests to determine significant differences in demographics and LOS between patients who experienced a hospital-acquired VTE and those who did not.

For the comparison of our automated calculation to standard clinical practice, we manually calculated the PPS through chart review within the first 2 days of admission on a subsample of 300 random patients. We powered our analysis to detect a difference in mean PPS from 4.86 to 4.36, enough to alter the point value, with 90% power and α = 0.05 (two-sided) and found 300 patients to be comfortably above the required sample size. We compared APPS and manual calculation in the 300-patient cohort using: 2-sample Student t tests to compare mean scores, χ2 tests to compare the frequency with which criteria were positive, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to determine capacity to predict a hospital-acquired VTE event. Pearson’s correlation was also completed to assess score agreement between APPS and manual calculation on a per-patient basis. After comparing automated calculation of APPS to manual chart review on the same 300 patients, we used APPS to calculate scores for the entire study cohort (n = 30,726). We calculated the mean of APPS by prophylaxis group and whether hospital-acquired VTE had occurred. We analyzed APPS’ ROC curve statistics by prophylaxis group to determine its overall predictive capacity in our study population. Lastly, we computed the time required to calculate APPS per patient. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics (IBM, Armonk, New York) and Python 2.7 (Python Software Foundation, Beaverton, Oregon); 95% confidence intervals (CI) and (SD) were reported when appropriate.

RESULTS

Among the 30,726 unique patients in our entire cohort (all patients admitted during the time period who met the study criteria), we found 6574 (21.4%) on pharmacologic (with or without mechanical) prophylaxis, 13,511 (44.0%) on mechanical only, and 10,641 (34.6%) on no prophylaxis. χ2 tests found no significant differences in demographics, LOS, or incidence of hospital-acquired VTE between the patients who received mechanical prophylaxis only and those who received no prophylaxis (Table 1). Similarly, there were no differences in these characteristics in patients receiving pharmacologic prophylaxis with or without the addition of mechanical prophylaxis. Designation of prophylaxis group by manual chart review vs. our automated process was found to agree in categorization for 39/40 (97.5%) sampled encounters. When comparing the cohort that received pharmacologic prophylaxis against the cohort that did not, there were significant differences in racial distribution, sex, BMI, and average LOS as shown in Table 1. Those who received pharmacologic prophylaxis were found to be significantly older than those who did not (62.7 years versus 53.2 years, P < 0.001), more likely to be male (50.6% vs, 42.4%, P < 0.001), more likely to have hospital-acquired VTE (2.2% vs. 0.5%, P < 0.001), and to have a shorter LOS (7.1 days vs. 9.8, P < 0.001).

Within the cohort group receiving pharmacologic prophylaxis (n = 6574), hospital-acquired VTE occurred in patients who were significantly younger (58.2 years vs. 62.8 years, P = 0.003) with a greater LOS (23.8 days vs. 6.7, P < 0.001) than those without. Within the group receiving no pharmacologic prophylaxis (n = 24,152), hospital-acquired VTE occurred in patients who were significantly older (57.1 years vs. 53.2 years, P = 0.014) with more than twice the LOS (20.2 days vs. 9.7 days, P < 0.001) compared to those without. Sixty-six of 75 (88%) randomly selected patients in which new VTE was identified by the automated electronic query had this diagnosis confirmed during manual chart review.

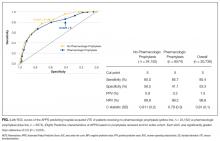

As shown in Table 2, automated calculation on a subsample of 300 randomly selected patients using APPS had a mean of 5.5 (SD, 2.9) while manual calculation of the original PPS on the same patients had a mean of 5.1 (SD, 2.6). There was no significant difference in mean between manual calculation and APPS (P = 0.073). There were, however, significant differences in how often individual criteria were considered present. The largest contributors to the difference in scores between APPS and manual calculation were “prior VTE” (positive, 16% vs. 8.3%, respectively) and “reduced mobility” (positive, 74.3% vs. 66%, respectively) as shown in Table 2. In the subsample, there were a total of 6 (2.0%) hospital-acquired VTE events. APPS’ automated calculation had an AUC = 0.79 (CI, 0.63-0.95) that was significant (P = 0.016) with a cutoff value of 5. Chart review’s manual calculation of the PPS had an AUC = 0.76 (CI 0.61-0.91) that was also significant (P = 0.029).

Distribution of Patient Characteristics in Cohort

Our entire cohort of 30,726 unique patients admitted during the study period included 260 (0.8%) who experienced hospital-acquired VTEs (Table 3). In patients receiving no pharmacologic prophylaxis, the average APPS was 4.0 (SD, 2.4) for those without VTE and 7.1 (SD, 2.3) for those with VTE. In patients who had received pharmacologic prophylaxis, those without hospital-acquired VTE had an average APPS of 4.9 (SD, 2.6) and those with hospital-acquired VTE averaged 7.7 (SD, 2.6). APPS’ ROC curves for “no pharmacologic prophylaxis” had an AUC = 0.81 (CI, 0.79 – 0.83) that was significant (P < 0.001) with a cutoff value of 5. There was similar performance in the pharmacologic prophylaxis group with an AUC = 0.79 (CI, 0.76 – 0.82) and cutoff value of 5, as shown in the Figure. Over the entire cohort, APPS had a sensitivity of 85.4%, specificity of 53.3%, positive predictive value (PPV) of 1.5%, and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 99.8% when using a cutoff of 5. The average APPS calculation time was 0.03 seconds per encounter. Additional information on individual criteria can be found in Table 3.