Hospital medicine and perioperative care: A framework for high-quality, high-value collaborative care

BACKGROUND

Hospitalists have long been involved in optimizing perioperative care for medically complex patients. In 2015, the Society of Hospital Medicine organized the Perioperative Care Work Group to summarize this experience and to develop a framework for providing optimal perioperative care.

METHODS

The work group, which consisted of perioperative care experts from institutions throughout the United States, reviewed current hospitalist-based perioperative care programs, compiled key issues in each perioperative phase, and developed a framework to highlight essential elements to be considered. The framework was reviewed and approved by the board of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

RESULTS

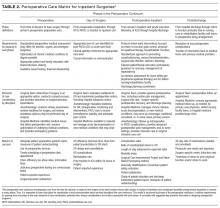

The Perioperative Care Matrix for Inpatient Surgeries was developed. This matrix characterizes perioperative phases, coordination, and metrics of success. Additionally, concerns and potential risks were tabulated. Key questions regarding program effectiveness were drafted, and examples of models of care were provided.

CONCLUSIONS

The Perioperative Care Matrix for Inpatient Surgeries provides an essential collaborative framework hospitalists can use to develop and continually improve perioperative care programs. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017;12:277-282. © 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Although a comprehensive look at the entire perioperative period is important, 4 specific phases were defined to guide this work (Figure). The phases identified were based on time relative to surgery, with unique considerations as to the overall perioperative period. Concerns and potential risks specific to each phase were considered (Table 1).

The PCMIS was constructed to provide a single coherent vision of key concepts in perioperative care (Table 2). Also identified were several key questions for determining the effectiveness of perioperative care within an institution (Table 3).

Models of Care

Multiple examples of hospitalist involvement were collected to inform the program development guidelines. The specifics noted among the reviewed practice models are described here.

Preoperative. In some centers, all patients scheduled for surgery are required to undergo evaluation at the institution’s preoperative clinic. At most others, referral to the preoperative clinic is at the discretion of the surgical specialists, who have been informed of the clinic’s available resources. Factors determining whether a patient has an in-person clinic visit, undergoes a telephone-based medical evaluation, or has a referral deferred to the primary care physician (PCP) include patient complexity and surgery-specific risk. Patients who have major medical comorbidities (eg, chronic lung or heart disease) or are undergoing higher risk procedures (eg, those lasting >1 hour, laparotomy) most often undergo a formal clinic evaluation. Often, even for a patient whose preoperative evaluation is completed by a PCP, the preoperative nursing staff will call before surgery to provide instructions and to confirm that preoperative planning is complete. Confirmation includes ensuring that the surgery consent and preoperative history and physical examination documents are in the medical record, and that all recommended tests have been performed. If deficiencies are found, surgical and preoperative clinic staff are notified.

During a typical preoperative clinic visit, nursing staff complete necessary regulatory documentation requirements and ensure that all items on the preoperative checklist are completed before day of surgery. Nurses or pharmacists perform complete medication reconciliation. For medical evaluation at institutions with a multidisciplinary preoperative clinic, patients are triaged according to comorbidity and procedure. These clinics often have anesthesiology and hospital medicine clinicians collaborating with interdisciplinary colleagues and with patients’ longitudinal care providers (eg, PCP, cardiologist). Hospitalists evaluate patients with comorbid medical diseases and address uncontrolled conditions and newly identified symptomatology. Additional testing is determined by evidence- and guideline-based standards. Patients receive preoperative education, including simple template-based medication management instructions. Perioperative clinicians follow up on test results, adjust therapy, and counsel patients to optimize health in preparation for surgery.

Patients who present to the hospital and require urgent surgical intervention are most often admitted to the surgical service, and hospital medicine provides timely consultation for preoperative recommendations. At some institutions, protocols may dictate that certain surgical patients (eg, elderly with hip fracture) are admitted to the hospital medicine service. In these scenarios, the hospitalist serves as the primary inpatient care provider and ensures preoperative medical optimization and coordination with the surgical service to expedite plans for surgery.

Day of Surgery. On the day of surgery, the surgical team verifies all patient demographic and clinical information, confirms that all necessary documentation is complete (eg, consents, history, physical examination), and marks the surgical site. The anesthesia team performs a focused review and examination while explaining the perioperative care plan to the patient. Most often, the preoperative history and physical examination, completed by a preoperative clinic provider or the patient’s PCP, is used by the anesthesiologist as the basis for clinical assessment. However, when information is incomplete or contradictory, surgery may be delayed for further record review and consultation.

Hospital medicine teams may be called to the pre-anesthesia holding area to evaluate acute medical problems (eg, hypertension, hyperglycemia, new-onset arrhythmia) or to give a second opinion in cases in which the anesthesiologist disagrees with the recommendations made by the provider who completed the preoperative evaluation. In either scenario, hospitalists must provide rapid service in close collaboration with anesthesiologists and surgeons. If a patient is found to be sufficiently optimized for surgery, the hospitalist clearly documents the evaluation and recommendation in the medical record. For a patient who requires further medical intervention before surgery, the hospitalist often coordinates the immediate disposition (eg, hospital admission or discharge home) and plans for optimization in the timeliest manner possible.

Occasionally, hospitalists are called to evaluate a patient in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) for a new or chronic medical problem before the patient is transitioned to the next level of care. At most institutions, all PACU care is provided under the direction of anesthesiology, so it is imperative to collaborate with the patient’s anesthesiologist for all recommendations. When a patient is to be discharged home, the hospitalist coordinates outpatient follow-up plans for any medical issues to be addressed postoperatively. Hospitalists also apply their knowledge of the limitations of non–intensive care unit hospital care to decisions regarding appropriate triage of patients being admitted after surgery.

Postoperative Inpatient. Hospitalists provide a 24/7 model of care that deploys a staff physician for prompt assessment and management of medical problems in surgical patients. This care can be provided as part of the duties of a standard hospital medicine team or can be delivered by a dedicated perioperative medical consultation and comanagement service. In either situation, the type of medical care, comanagement or consultation, is determined at the outset. As consultants, hospitalists provide recommendations for medical care but do not write orders or take primary responsibility for management. Comanagement agreements are common, especially for orthopedic surgery and neurosurgery; these agreements delineate the specific circumstances and responsibilities of the hospitalist and surgical teams. Indications for comanagement, which may be identified during preoperative clinic evaluation or on admission, include uncontrolled or multiple medical comorbidities or the development of nonsurgical complications in the perioperative period. In the comanagement model, care of most medical issues is provided at the discretion of the hospitalist. Although this care includes order-writing privileges, management of analgesics, wounds, blood products, and antithrombotics is usually reserved for the surgical team, with the hospitalist only providing recommendations. In some circumstances, hospitalists may determine that the patient’s care requires consultation with other specialists. Although it is useful for the hospitalist to speak directly with other consultants and coordinate their recommendations, the surgical service should agree to the involvement of other services.

In addition to providing medical care throughout a patient’s hospitalization, the hospitalist consultant is crucial in the discharge process. During the admission, ideally in collaboration with a pharmacist, the hospitalist reviews the home medications and may change chronic medications. The hospitalist may also identify specific postdischarge needs of which the surgical team is not fully aware. These medical plans are incorporated through shared responsibility for discharge orders or through a reliable mechanism for ensuring the surgical team assumes responsibility. Final medication reconciliation at discharge, and a plan for prior and new medications, can be formulated with pharmacy assistance. Finally, the hospitalist is responsible for coordinating medically related hospital follow-up and handover back to the patient’s longitudinal care providers. The latter occurs through inclusion of medical care plans in the discharge summary completed by the surgical service and, in complex cases, through direct communication with the patient’s outpatient providers.

For some patients, medical problems eclipse surgical care as the primary focus of management. Collaborative discussion between the medical and surgical teams helps determine if it is more appropriate for the medical team to become the primary service, with the surgical team consulting. Such triage decisions should be jointly made by the attending physicians of the services rather than by intermediaries.

Postdischarge. Similar to their being used for medical problems after hospitalization, hospitalist-led postdischarge and extensivist clinics may be used for rapid follow-up of medical concerns in patients discharged after surgical admissions. A key benefit of this model is increased availability over what primary care clinics may be able to provide on short notice, particularly for patients who previously did not have a PCP. Additionally, the handover of specific follow-up items is more streamlined because the transition of care is between hospitalists from the same institution. Through the postdischarge clinic, hospitalists can provide care through either clinic visits or telephone-based follow-up. Once a patient’s immediate postoperative medical issues are fully stabilized, the patient can be transitioned to long-term primary care follow-up.